Aruna Chakravarti writes of the Bauls (wandering minstrels) of Bengal and the impact their syncretic thought, music and life had on Tagore

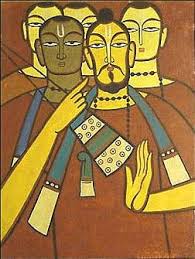

Religious movements such as Bhakti and Sufi have spanned time and territory and entered Bengal, in successive waves, creating a syncretic culture in which music and poetry are amalgamated. One of the forms in which these movements find creative expression is Baul Gaan —the singing of itinerant minstrels.

Universally recognised as foremost among the oralities of Bengal, the Baul Sampradai is a community for whom singing is synonymous with worship. The Baul expounds a philosophy of humanism which rejects religious orthodoxies and stresses human equality irrespective of caste, class, religion and gender. The Baul sets himself on a spiritual journey, lasting a lifetime, towards discovering his moner manush (man within the heart) thereby alienating the notion of seeking the Divine in external forms such as mosques, temples, images and sculptures. Since God is believed to reside within man, the human body is viewed as the site of the ultimate truth –that which encompasses the entire universe. This tenet of Baul philosophy is known as deha tatwabad—the belief that the soul being pure the body that houses it, together with all its functions, is pure and holy.

Concentrated mostly in Kushthia, Shilaidaha and Sajadpur in East Bengal (now Bangladesh) and Murshidabad and Birbhum in West Bengal, the Baul tradition, though drawing elements from Tantra, Shakta and Sahajiya[1], stems from two main sources — Muslim Sufi and Hindu Vaishnav. Hence the simultaneous presence of Hindu and Muslim bauls in the villages of Bengal and great composers from both streams—Lalon Fakir, Duddu Shah, Madan Baul, Gagan Harkara and Fakirchand. Rejecting religious codes such as Shariat and Shastras, caste differences, social conventions and taboos, which they see as barriers to a true union with God, they sing of harmony between man and man. “Temples and mosques obstruct my path,” the Baul sings, “and I can’t hear your voice when teachers and priests crowd around me.”

Refusing to conform to the conventions of religion and caste ridden Bengali society, Bauls (the word is sourced from the middle eastern bawal meaning mad or possessed) are wandering minstrels who sing and dance on their way to an inner vision. Essentially nomadic in nature walking, for them, is a way of life. “No baul should live under the same tree for more than three days” — the saying seems to stem from the Sufi doctrine of walking an endless path (manzil) in quest of the land where the Beloved (the Divine) might be glimpsed. Bauls live on alms which people give readily. In return the Baul sings strumming his ektara[2] with dancing movements. The songs are rich with symbolism, on the one hand, and full of ready wit and rustic humour on the other. The Baul rails against the hypocrisy of religion and caste and takes sharp digs at the clergy but totally without rancour.

Many of the composite forms found in an older culture of Bengal have become sadly obscured in the present scenario of identity politics. But the one that has not only survived but is gaining in recognition day by day, is the Baul tradition. This is, in no small measure, owing to the intervention and interest taken by Rabindranath Tagore. In his Religion of Man Rabindranath tells us that, being the son of the founder of the Adi Brahmo Samaj, he had followed a monotheistic ideal from childhood but, on gaining maturity, had sensed within himself a disconnect from the organised belief he had inherited. Gradually the feeling that he was using a mask to hide the fact that he had mentally severed his connection with the Brahmo Samaj began tormenting him. And while in this frame of mind, travelling through the family estates in rural Bengal, he heard a Baul sing. The singer was a postal runner by the name of Gagan Harkara and the song was “Ami kothai paabo tare/ amaar moner manush je re[3].”

“What struck me in this simple song,” Rabindranath goes on to say, “was a religious expression that was neither grossly concrete, full of crude details, nor metaphysical in its rarefied transcendentalism… Since then, I’ve often tried to meet these people and sought to understand them through their songs which are their only form of worship.” In his Preface to Haramoni[4], Rabindranath makes another reference to this song. Quoting some lines from the Upanishads— Know him whom you need to know/ else suffer the pangs of death— he goes on to say, “What I heard from the mouth of a peasant in rustic language and a primary tune was the same. I heard, in his voice, the loss and bewilderment of a child separated from its mother. The Upanishads speak of the one who dwells deep within the heart antartama hridayatma[5]and the Baul sings of the moner manush. They seem to me to be one and the same and the thought fills me with wonder.”

Lalon Fakir’s commune was located in the village of Chheurhia which fell within Rabindranath’s father’s estates. Though there is no authentic record of a meeting between the two, it is a fact that the poet was the first to recognise Lalon’s merit which had the quality of a rough diamond. His inspiration was powerful and spontaneous but, lacking in clarity of expression, lay buried in obscurity till Rabindranath brought it out into the open. Publishing some of the songs in some of the major journals of the time, Rabindranath took them to the doors of the educated elite. Not only that. They gained in popularity from the fact that he, himself, often used Baul thought and melody in his own work. “In some songs,” he tells us in his Manush er Dharma[6], “the primary tunes got mixed up with other raags – raaginis which prove that the Baul idiom entered my sub conscious fairly early in life. The man of my heart, moner manush, is the true Devata[7]. To the extent that I’m honest and true to my knowledge, action and thought — to that extent will I find the man of my heart. When there is distortion within, I lose sight of him. Man’s tendency is to look two ways — within and without. When we seek him without — in wealth, fame and self- gratification — we lose him within.”

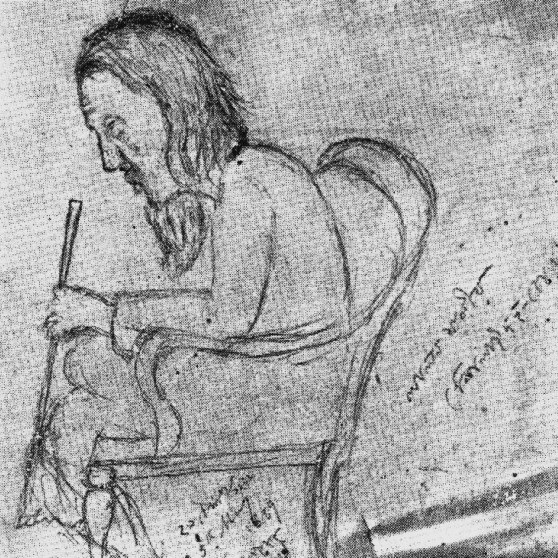

But it wasn’t only in his compositions that Rabindranath disseminated Baul ideology. It went deeper than that. The primitive simplicity and freedom of Baul thought and living charmed him so completely that he started imbibing them in his own lifestyle. He grew his hair long, kept a flowing beard and wore loose robes. He created Baul like characters in his plays and dance dramas and enacted the roles himself. And, as he grew older, a restlessness; an inability to stay in one place took hold of him. Leaving the ancestral mansion of Jorasanko he relocated to Santiniketan but even there he could not stay in the same house for more than two months. In the last two and half decades of his life, a tremendous wanderlust seized him. He travelled extensively both within the country and without, earning for himself the sobriquet of ‘roving ambassador for India’.

Perhaps, the most powerful testimony of the evolution of Rabindranath from a princely scion of the Tagores of Jorasanko to the man he finally became is found in Abanindranath’s portrait of his uncle. It depicts an old man with flowing white locks and beard, wearing a loose robe and holding an ektara high above his head. The limbs are fluid in an ecstatic dance movement. It is a significant fact that the painting is titled Robi Baul.

[1] Different schools of philosophy and religion. The Sahajiya is a philosophy that embrace nature and the natural way of life.

[2] String instrument

[3] Translates from Bengali to: “Where will I find Him — He who dwells within my heart”

[4] The Haramoni (Lost Jewels) is 13-volume collection of Baul songs compiled by Mansooruddin to which Tagore wrote the preface for the first volume published in 1931

[5] Translates to ‘innermost part of the heart and soul’

[6] Collection of Lectures by Tagore in Bengali, published in 1932

[7] Translates to “God’

Aruna Chakravarti has been the principal of a prestigious women’s college of Delhi University for ten years. She is also a well-known academic, creative writer and translator. Her novels, Jorasanko, Daughters of Jorasanko, The Inheritors, Suralakshmi Villa and The Mendicant Prince have sold widely and received rave reviews. She has two collections of short stories and many translations, the latest being Rising from the Dust. She has also received awards such as the Vaitalik Award, Sahitya Akademi Award and Sarat Puraskar for her translations.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International