Book Review by Somdatta Mandal

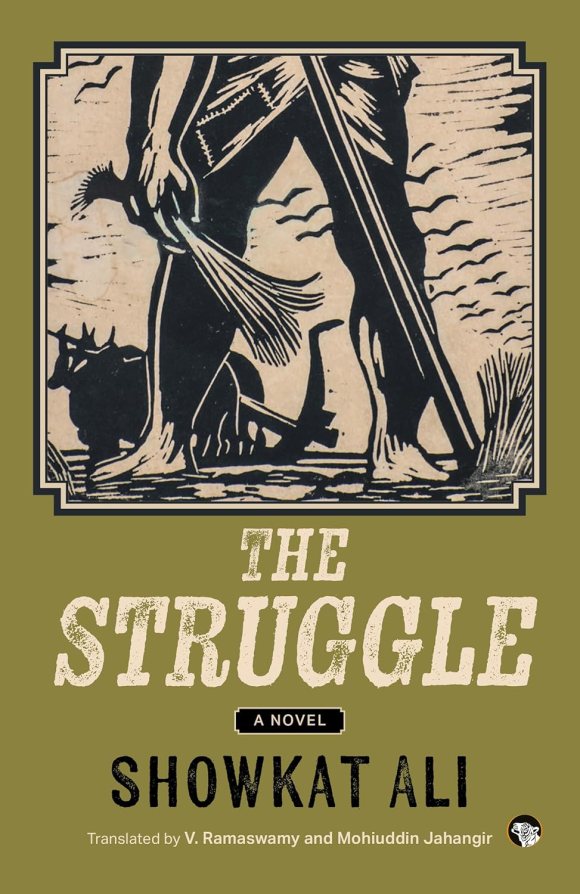

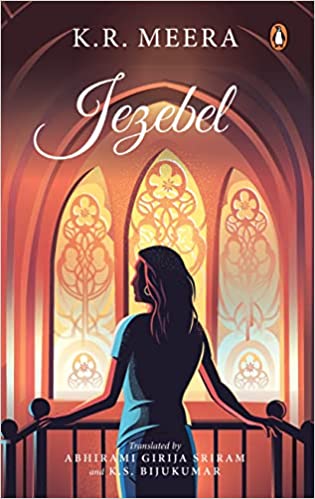

Title: Jezebel

Author: K.R. Meera, translated from Malayalam by Abhirami Girija Sriram and K. S. Bijukumar)

Publisher: Penguin Random House India

In a multicultural and multilingual country like India, it is very difficult to ascertain the progress of literary creativity in all the regions because of language barriers. Translation is one of the means through which this deficiency can be met. Recently even big publishing houses are paying a lot of attention to translate texts from different bhasha[1] literatures into English so that they can cater to a pan-Indian readership. K.R. Meera’s original Malayalam novel Jezebel is one such recent addition. It has the eponymous protagonist Jezebel, a young doctor in Kerala, struggling against the cruel realities of a patriarchal world –realities that not even her education, resolve or professional brilliance can shield her from. Trapped in an abusive and claustrophobic marriage that had been arranged by one of her relatives for some ulterior motive, the novel begins with a powerful metaphor of suffering and endurance:

“As she stood in the family court, pelted with the blame of having paid a contract killer to murder her husband, Jezebel had this revelation: To endure extreme torture, imagine yourself as Christ on the cross.”

In this novel, which takes the form of a courtroom drama to show us the rich inner worlds of its characters, we see Jezebel reflect on her life and its pivotal points as she takes the stand. Through her memories, we see her grow from a reticent, serious young woman to a rebel who refuses to bend to the conventions of society. In the Old Testament of the Bible, Jezebel was a prophet and she was the only one to challenge prophet Elijah. She was at the same time a strong woman and an accursed one. Like the Biblical story of Queen Jezebel, who was much maligned as a scheming harlot and infamously thrown to her death from her palace window, Jezebel is a novel that asks if independent women can ever live lives that are free of judgement. The marriage between Jezebel and Ahab was an agreement between two communities that worshipped two different gods. Poor King Ahab was a good king who ruled for twenty-two years. His only mistake was to marry the Sidonian princess Jezebel. And that too to improve relations between the two kingdoms and to trade with them. When they got married, Queen Jezebel brought her gods along with her to Samaria. In our protagonist’s case, her already contentious divorce proceedings go suddenly awry, and her unhappy marriage holds complex secrets. Throughout the novel, K.R. Meera’s powerful prose makes resonant allusions to the Bible in different ways that elucidate the correlations between legend and the protagonist’s life while also exploring how sexuality and gender roles are manipulated by the dictates of society.

In the novel we are shown how Jezebel’s arranged marriage with Doctor Jerome George Marakkaran ended in disaster from day one, and in the two and a half years they lived together as husband and wife, their marriage was never consummated. Her father-in-law, George Jerome Marakkaran is a brute straight from TV serials, and starts cursing Jezebel right from the first day believing in his god-ordained mission to punish her in any form whatsoever. The court hearings frame the narrative, with the (very filmy) lawyer’s dramatic queries triggering flashbacks, each a tale of tremendous misery, shocking injustice or unbearable trauma – a veritable catalogue of the woes of a half of the world even in this day and age. The mother-in-law, Lilly George Marakkaran, however, is kind-hearted even if meek, and she too secretly supports her daughter-in-law to break the shackles of patriarchy and go out into the world – something she was unable to do. This inability leads to her suicide in the end. Jezebel’s parents, too, are characters who refuse to come out of clichés. The result is a series of unfortunate events, and they all end up in a family court for divorce. In order to narrate the plight of her protagonist from the very beginning, Meera creates the canvas with plenty of characters, who like Chaucer’s ‘God’s plenty’ fill the pages of the novel from the beginning to the end. Most of these characters are stereotypes and yet they manage to make the story convincing, though melodramatic at times. Jezebel has a difficult childhood growing up with her mother Ammachi who explains every move in Biblical terms and who argues that “a good woman will not ever speak a word” against her husband, however worthless he is; her maternal grandmother Valiyammachi is the one who understands her and asks her to discontinue her marriage immediately and live life on her own terms. Throughout the novel she offers her shoulders for Jezebel to weep upon.

In between, a lot of melodrama is thrown in. The novel itself confesses the soap opera part:

“John’s wedding was a frugal affair. George Jerome Marakkaran stood ramrod stiff, hands clasped behind his back, chin tilted up at a hundred-and-twenty degrees. In his sandalwood-coloured silk jibba and gold-bordered mundu, he looked every bit the father in television serials.”

The rigid patriarch that he is, George Jerome Marakkaran is no exception; almost all characters and situations befit TV serials. There are no surprises, no nuances, no gray between black and white. To give an entire cross-section of society, we have sympathetic characters like Father Ilanjikkal from the nearby church, Jezebel’s uncle Abraham Chammanatt, who was a party to the injustice inflicted upon her and to whom she begs, “Please give me back my life. That’s all. My happiness …my ability to laugh.” We also have sexually abused children, references to other broken marriages, gay relationships, the story of Advait, who had undergone a sex-change surgery to become a man, and who tells Jezebel, “To prove that a man is a man and a woman is a woman, you need a certificate.” On another occasion explains it thus:

“‘Society is a great playwright, Jezebel. Our job is to act out our cliched roles again and again in the ancient play that it has scripted. Every role has its prescribed dress code, make-up, hairstyle, and dialogue. Our job is to play those roles, no matter how ill-fitting the costume, without changing the course of the script. If I decide to change my costume midway through the play, then what will happen to the play? What will the audience, eager to hear a story that they like, do?’ he sighed.”

Amidst the struggle of Jezebel to come to terms with society, Meera also mentions the flitting relationships that Jezebel undergoes with different men and all of which fizzle out due to different reasons. When her lawyer informs her that the verdict for her divorce suit would come out soon, this is how Jezebel reacts:

“Verdict? What verdict? Verdict against whom? In an instant, Jezebel was flung from heaven to the netherworld. She despaired about the she-who-was, and the she-who-had-been. She felt emboldened thinking about the she-who-would-be, though. Just then, she saw four creatures in the centre of and around the throne under the sea. They had many eyes in the front and the back. The first creature looked like Ranjith, the second had Jerome’s face, the third resembled Nandagopan, the fourth had Kabir’s looks. The four creatures had six wings each, many eyes all around and within. They proclaimed day and night. In their midst, she saw a lamb that looked like it had been slain.”

Each ordeal leads the reader to the next in a highly skilfully woven narrative that becomes unputdownable after the opening. That, arguably, is what Meera is aiming for, getting every reader to care for the fate of the characters no matter how stereotypical they might be. Indeed, their being stereotypes helps in making the story universal, whereas nuances and specifics might have made it different. While Meera’s story-telling abilities are way above average, the simplistic treatment of many subplots may mar the reading experience for a few readers. Paradoxically, that is what at the same time may compel the kind of readers who don’t bother about ‘feminism’ and ‘patriarchy’ to keep reading this novel till the end, and even think through it.

Jezebel reflects on her life and its pivotal points as she takes the stand. Through her memories, we see her grow from a reticent, serious young woman to a rebel who refuses to bend to the conventions of society. Jezebel is a novel that asks if independent women can ever live lives that are free of judgement. K.R. Meera’s prose, in this elegant translation from the Malayalam by Abhirami Girija Sriram and K.S. Bijukumar, makes resonant allusions to the Bible in powerful ways that elucidate the correlations between legend and the protagonist’s life while also exploring how sexuality and gender roles are manipulated by the dictates of society.

The beginning of the novel is set seven years after that day the Marakkaran family arrives at Jerusalem, Jezebel’s home, to “appraise” her. A broken Jezebel is facing a barrage of questions from Jerome’s lawyer in a family court which is hearing her divorce petition. She feels like Jesus Christ on the cross, enduring extreme torture. There is yet another round of accusations, all built around an alleged attempt to murder her husband. A courtroom saga begins as Jezebel looks back and remembers scenes from her marriage that brought her exciting life and career to a screeching halt.

Jezebel’s is not the only story of suffering in the novel. There is Sneha, a schoolgirl traumatised by the sexual abuse at the hands of her math teacher, and Angel, a four-year-old girl, who survived a mass suicide by her family because of debts, only to be sexually assaulted by her sixty-year-old neighbour. Jezebel is also a story of the will to survive physical and mental wounds and standing up to force the change of a medieval mindset. Anitha, one of the novel’s characters, picks up the brushes to become an artist after both her husband and lover abandon her. And Jezebel stands tall above everybody else while she fights a system rigged in favour of men. The novel is a serious attempt to end the silent suffering of gender injustices in homes and outside, especially when women find themselves always constrained by the limits that patriarchy imposed upon them. Indeed, the work is a testament to the fact that even in this modern age, in India at least, patriarchal social norms wield an inordinate power over women and restrict their ability to exercise their agency and achieve self-determination.

Reading through the 390 pages of a novel is not an easy task but the way K.R. Meera manages to retain the reader’s interest is praiseworthy. Despite having so many stereotypical characters strewn throughout the narrative, Meera’s manner of storytelling is unique and like a detective novel one often goes on guessing what happened next.

The book drags a little towards the end and would have read much better if some sort of precision was adopted in the narrative technique. To remain politically correct and elaborate on the reasons and ramifications of the story line sometimes, such details may have been unnecessary.

In the author’s acknowledgements section Meera states that she shadowed Dr. Dhanya Lakshmi in her professional life and for verifying the medical facts and interpretations in the novel. In some places these details seem superfluous and could have been avoided. The author also thanks the advocates who accompanied her to Kottayam’s family courts and observed the court proceedings. The way the interjections of the lawyer and the judge are narrated in the novel sometimes seems rather contrived as the author seems to rely on sensationalism as found in films. The translators use informal expressions in Malayalam for the retention of the local idiom and unlike several other translated texts where the reader is often confused because different relationships are addressed in the local lingo, in this novel it does not seem so. Finally, the way issues of ‘feminism’ and ‘patriarchy’ – the two main thrust areas of the novel – that plague contemporary society in Kerala even today, are wonderfully resolved by the author must be mentioned. K.R. Meera tried to break free from Malayalam literary traditions. Jezebel’s reluctance to take a stand for herself in the novel and the consequent adversities in her life tell a tale of epistemic marginalization. According to the author, “I have seen bold, patient women take their time to stand up for themselves. What we often forget is that to sprout wings, one must go through the stages of being a cocoon and a pupa.” The last sentence of the novel therefore speaks of the resilience of Jezebel when she turned her face up to the sun. The old Jezebel was no more. The new Jezebel is one who received the revelation — “And so, the woman adorned with the sun will weep and wail no more.” The novel is recommended to all readers who will find interest in reading about contemporary Christian society in Kerala and realise that societies in other parts of India are also not free from accepting a powerful educated woman who wants to live her life without paying heed to the shackles imposed at every step through patriarchal domination.

[1] Language

Somdatta Mandal, academic, critic and translator, is a former Professor of English at Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, India.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International