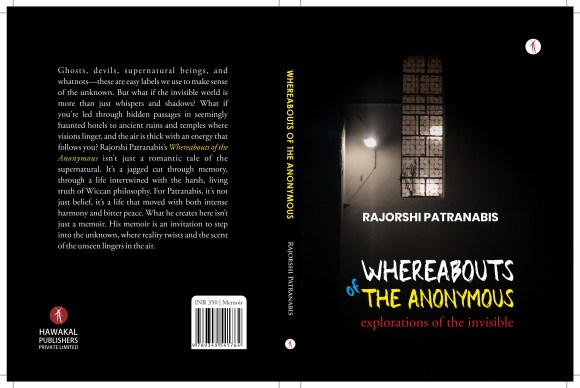

A brief discusion of Whereabouts of the Anonymous: Exploration of the Invisible by Rajorshi Patrnabis, Hawakal Publishers, with an exclusive interview with the author on his supernatural leanings

Whereabouts of the Anonymous: Exploration of the Invisible by Rajorshi Patrnabis could have been a regular book of intense ghost stories, with the oldest ‘presences’ dating back to the regime of Sher Shah Suri (1472 – 1545). ‘Presences’ are basically spirits — visible or barely visible — that cause disturbances in the energy field surrounding us, as per the book.

One of the most coherent of these ‘spirits’ was from 1920, confiding her story on Christmas eve — reminds one of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol and Uncle Scrooge — only this spirit was a British woman from the Raj era, a spirit that lost her beloved who was from a Bengali royal family. Her strict father stepped in and stopped the marriage. No one knew what happened to the groom. And she continued to weep and wait while haunting the premises of the popular and populous Park Street where she was supposed to meet her beloved more than a hundred years ago… Then there’s a ghost that takes you back to his funeral pyre… drawing back the curtain between the two dimensions — one in which we exist and one in which they hover…

These, however, are not your regular ghost stories. There is a difference for Patranabis claims to have met these sad spirits in real life.

A Wiccan by choice, Patranabis has tried to draw back the curtains to reveal a dimension whose existence is elusive and avoidable for most of us at best and rejected by many. He claims to have a spiritual bent of mind which helps him experience these out-of-the-box scenarios, meet the dearly departed. He has done a number of books of poetry around his beliefs. He has even photographed these spirits!

Though the images are blurry at the first viewing, you have to focus hard to see the ethereal outlines of shadows beyond the realm of the living, I guess.

Whereabouts of the Anonymous is a memoir that spans his interactions with, as the title says — ‘the anonymous’ — or the blurry ‘presences’ and explores the invisible for majority of the spirits are merely depicted as shadowy in his narrative as in his photographs except for a few whose images have not been taken.

Occasionally, the spirits can be malevolent as in the Bhangarh Fort, where a foul-smelling female spirit and some lost souls in the ancient jails wounded Patranabis physically and chased him out. Set in the Aravalli hills of Rajasthan. Bhangarh is the most haunted place in India. There is a story of a princess and her spurned lover associated with it. Evidently, a sage fell in love with the princess and made a special concoction which would make her fall in love with him. When she went to buy a perfume, the smitten lover tried to replace it with his love potion. The princess threw away the bottle of love potion. It fell on a rock, dislodging it. The rock rolled down to kill her admirer, who cursed her with his dying breath!

There is also the narrative about a whole village that accepts and lives in peace with the spirits of their dearly departed, even giving them rickshaw rides and offering them chairs!

Patrnanabis has brought his Wiccan outlook into the discourse. His language flows. The narrative is simple and easy to understand. The descriptions are so graphic that one can almost visualise the disembodied spirits and their interactions. The 150-page book is an enjoyable and easy read and a perfect companion for travel or an evening or two. But the author’s experiences and his interests stretch beyond what the pages can hold. In this interview, we discuss his beliefs and his experiences…and maybe, another book?

How old were you when you had your first supernatural sighting? Were you scared the first time?

When I look back, the first time that I had a feel of the ‘other dimension’ was perhaps at the age of 7 or 8. I remember going to my paternal home at Digboi during our winter vacations. I remember going to my parent’s bedroom at the first floor and my mother used had to send me to her room to fetch something. The room was across a terrace, and I remember running through the terrace from the staircase to the room. But every time, I could feel someone running with me through the terrace. But as and when I would enter the room, it was all perfect. I would run back again again to the stairs. When I would blurt this out to my parents, they would simply ignore me, but somehow, I was never completely convinced. It was much later, sometime around the year 2000 that my father confided with me of a real ‘presence’ there. He told me that there had been many an experience where people had felt the presence of something eerie there. But by then I had had some very deep experience of the supernatural existence.

When did you become a Wiccan and why?

The answer to this ‘why’ is a wee bit dicey. I am myself not sure of this. It was just a flow that I couldn’t control. Mind you, I had already gone through some extremely remarkable experiences and my stint at the hill top temple and my encounter with that 97 year old person who taught me numerology was way before I joined Wicca. I would call myself pretty insane in those phases of my life. By the time Wicca happened, I had calmed down considerably and joining my teacher was nothing less than an accident. It so happened that my friend, Subhodip, and I were walking down the Southern Avenue in Kolkata when we spotted another school friend ( a senior Wiccan) standing at the door of an otherwise inconsequential book store. He waved at us and asked us to join in, as it was an open session by my teacher. We joined. Subhodip was skeptical, while I followed it up with an email and I was called for an interview with Ma’am. The journey started. I had mentioned about my experience in ‘Whereabouts…’ This was early 2013.

Did becoming a Wiccan help you align to the supernatural better?

Infact, my Wiccan knowledge taught me the nuances of alignment with the forces of nature. Why just the supernatural? The vibrations that the earth emanates, the animal kingdom throws out, to feel and spot across dimensions etc. The most important thing is perhaps the use of sound like the chatter of a rainfall, the melodies of a singing bowl or even drum beats (like in Voodoo) as means of invocation, that, was passed on to me. More than anything, the pleasures of immersing oneself in ancient knowledges can be very ‘intoxicating’. Our school concentrates most on the Egyptian origins. If you ask me now, I worship Goddess Isis as my altar Goddess along with the 64 yoginis. Yes, Wicca has helped align myself to me, if I say this philosophically.

You have called yourself ‘spiritual’ and also spoken of ‘seers’? Can you explain these two terms?

I wouldn’t get into the linguistic trap of English. But a Wiccan would say spiritual comes from ‘spirit’. A very basic tenet of Wicca is to align your body, mind, soul and spirit. As and when the becomes one with nature does your mind uplift itself to being a soul. A soul that gets through the rigours of lust becomes a spirit. We are in the habit of using the word spirituality very lightly, but a true Wiccan would say that a pure spirit sits on the pinnacle of the pyramid. There are many references in our Sanatan scriptures too about such spirits and the recourse they take to leave the body, as and when they cross over.

A seer is a saint who has won over the realms of the physical nuances. He/she is automatically clairvoyant as all their faculties have attained the higher plains in the atmosphere. Please don’t mistake a seer for only a saint. A scientist or a litterateur who had immersed themselves in the claustrophobic depths of knowledge can be a seer too. Many such examples can be sighted to prove this.

How did/does your family respond to your being a Wiccan or interacting with spirits?

My family doesn’t always subscribe to what I do, but in all honesty they had never been a hindrance to my learnings. There are Wiccan ceremonies that I celebrate or spells that I do from time to time for the well being of people, they had all along been very supportive. They stand as a pillar beside me.

When and why did you turn to writing?

I started writing at a very young age. My first poem, if I can recall was at the age of 13. But as time went on, everything slowed down. My next phase was from 2015 and my first published book was in 2018. By this phase I was well and truly into Wicca.

You have used Japanese techniques in poetry to describe your journey as a Wiccan and to interact with spirits. Why? Do these align better to help you describe your experiences?

Well, I wouldn’t say I use Japanese poetry forms to interact with any spirit. Though I must accept that I’ve had communications with the other dimension which were very poetic at times. In my book, Gossips of our Surrogate story, I had used quite a bit from my Wiccan Book of Shadows and even you had accepted that they were poems alright, good or bad, notwithstanding. But I would also like to harp on the inherent pertinence of this question. Gogyokha or Gogyoshi are short form poetry in just 5 lines and my forays into the other dimension had just had similar experiences — short, crisp and at most times life altering. In my Gogyoshi collection, Checklist Anomaly, all the poems are either true happenings or near life occurings. My writing (poetry) as a whole, until now, had been with deep metaphysical love. Perhaps my thought process is challenged. But Japanese forms had been a huge compliment to this particularly weird handicap of mine.

What made you think of doing this book — your memoir of supernatural interactions so to speak?

To be very honest, all these experiences that I had shared in Whereabouts of the Anonymous would have stayed with me through out this physical life had it not been for a dear brother and publisher, Bitan Chakraborty. It was on his persistent insistence that I decided to put my ‘stories’ on paper. But that was again a very difficult thing. I really had to scoop things from the nook and crannies of my memory to make for a reasonably good compilation. Even Bitan had certain experiences with me or otherwise ( like his camera giving up on a particular shot etc.) and was most interested on such a memoir seeing the light of the day. I have dedicated this book to Bitan. I had to, it was his brainchild and as a Wiccan would say, the Universe made me write it.

You seem to seek out departed spirits or ghosts. Why? Are you not scared?

I find this word ‘ghosts’ very disrespectful. Departed spirits, well, if you ask me no spirits depart. Remember, the law of conservation of energy — the total energy remains constant, it can neither be created nor be destroyed. The energies ( whether spirits or not) have this affinity to get in touch with other souls who can feel them and with a little effort can hear them. The ectoplasmatic fusions that happen inside the cosmos are mostly not registered by ‘so called science minded sceptics’. There are gadgets to measure such vibes. And afraid? No. You would only be afraid if you stay in denial of the other dimension. If I say that the other dimension is omnipresent, no matter what, you won’t be afraid of it. Remember you are afraid of darkness because you don’t see through it, but as soon as you put on a light, it becomes a part of you. Precisely the unknown is magic or mysticism and the known is science.

Do you only sight spirits or auras around people? Are you into Noetics as a subject?

Auras form the atmosphere, it really doesn’t matter whether you have a body or not. There are ascetics who would ask you not to touch anyone’s feet while paying obeisance. The say, the aura or the protonic energy of a person is as long as that person’s height. They say you put your head on the ground, possibly, to absorb a concoction of the Earth’ s magnetism coupled with the aura of that person. By the bliss of this Universe, I do feel a few energies that are devoid of a body. Noetics or the consciousness levels automatically become part of these. But I am personally not into Noetic sciences or research. But ancient knowledges under the umbrella of Wicca does take you through the subconscious to superconscious levels of the mind with twinings of the nature, supernature and the supernatural. There are very thin lines segregating them.

In you memoir, you keep asking people to leave a glass of water to satiate the spirit. Do you see yourself as a person who appeases ghosts? Do you help people – how do they reach out to you if they feel a ‘presence’?

What does a glass of water do? Think of a situation where you stand in front of everyone, yet you’re being ignored by everyone. You would not realise that you’re actually not visible to them. Just think of the insecurity that you would have to realise that persons whom love so dearly are slowly getting ahead with life and that you have become a fading memory. That glass of water just reinstates the faith that he/she still matters to you.As time goes, like all energies, they would also dissipate. But with pleasantness in them.

I don’t appease anyone. As my teacher says, it’s all about alignment. If I may say so, the Universe makes me do certain things that a psychiatric practitioner would do to people with mental illness. These are very small techniques that I had learnt over the years to put a restless soul to a restful state. As far as the last part of your question is concerned, I don’t do anything for any consideration. I have a promise to keep. If the cosmos so wills that I would be of help to someone, I would definitely land up from nowhere.

Do you plan to do something with this ‘gift’ you have? Can you see spirits where others cannot? Will you be doing more books about your supernatural experiences?

Well, after the book went for print, I realised that I could have included many more of the experiences that I had gone through. So, another book is very much in the offing. And as far as doing something with this ‘gift’ is concerned, I am completely in sync with you that this is a ‘gift’ that the cosmos had bestowed upon me and when you have such an invaluable gift, you keep them. You generally don’t use them. Seeing spirits? I feel them and I see them only when the spirit wants to show them off (like the school Master of Bhanjerpukur – one of my most remarkable experiences).

(This review and online interview by email is by Mitali Chakravarty)

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International