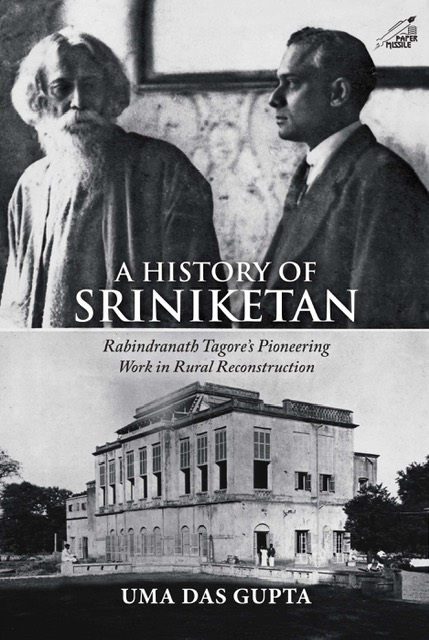

In Conversation with Professor Uma Das Gupta, Tagore scholar, author of A History of Sriniketan: Rabindranath Tagore’s Pioneering work in Rural Reconstruction published by Niyogi Books, 2022

Tagore (1861-1941) has been celebrated as one of the greatest poets of the world, a great philosopher, a writer, an artist, a polyglot but what did the maestro himself perceive as his greatest ‘life work’?

He wrote: “My path, as you know, lies in the domain of quiet integral action and thought, my units must be few and small, and I can but face human problems in relation to some basic village or cultural area. So, in the midst of worldwide anguish, and with the problems of over three hundred millions staring us in the face, I stick to my work in Santiniketan and Sriniketan hoping that my efforts will touch the heart of our village neighbours and help them in reasserting themselves in a new social order. If we can give a start to a few villages, they would perhaps be an inspiration to some others—and my life work will have been done.” This was in a letter in 1939 to an agricultural scientist, Leonard Elmhirst (1893-1974), who helped him set up Sriniketan, a craft and agricultural development project for the villages which fell under the purview of the Tagore family zamindari.

To Tagore, his ‘life work’ lay in the welfare of humankind and poetry was just one of the things he did, like breathing. He told a group of writers, musicians, and artists, who were visiting Sriniketan in 1936: “The picture of the helpless village which I saw each day as I sailed past on the river has remained with me and so I have come to make the great initiation here. It is not the work for one, it must involve all. I have invited you today not to discuss my literature nor listen to my poetry. I want you to see for yourself where our society’s real work lies. That is the reason why I am pointing to it over and over again. My reward will be if you can feel for yourself the value of this work.”

These are all incidents woven into a book called A History of Sriniketan by historian and Tagore biographer, Uma Das Gupta, who did her post-doctoral research on the maestro and the history of the educational institutions he founded at Santiniketan and Sriniketan. She moved out of Oxford and pursued her studies in Calcutta. She has highlighted Tagore uniquely as an NGO (Non-governmental organisation) operator and also an educator. Mahasweta Devi (1926-2016) in her book Our Santiniketan, recently translated by Radha Chakravarty, focussed on his role mainly as an educator who sought to revive values, a love for nature along with rigorous academics to create thinkers and change makers like the author herself.

A History of Sriniketan is about his work among villagers to bridge gaps. Often, his poetry and writing expresses the empathy he felt for pain and suffering, his need to instil beauty and well-being into humankind so that they could evolve towards a better world — an ideal which he described to an extent in poems like ‘Where the Mind is Without Fear’ and India’s national anthem.

Dasgupta did this by not only delving into Tagore’s own writings but by devoting her life to unearth the depth of the maestro’s commitment and the hard work and money he invested in the project he described as his ‘Life’s work’. She even visited the villages and talked to the beneficiaries and workers. Her book is peppered with photographs of Tagore in Sriniketan. It is amazing to see pictures of the poet with people from Sriniketan sitting on the ground or celebrating festivities.

Tagore, Das Gupta tells us, poured all his Nobel prize money, into the Sriniketan Bank project which was led by his son, Rathindranath. The project hoped to free the peasant from debt. How well were these experiments received by Tagore’s contemporaries? Das Gupta writes in her book: “It would not be an exaggeration to say that Rabindranath had to encounter all of those things, that is, to ‘overcome opposition’ and to ‘conquer space and time’, in no uncertain measure. In short, he had to drive hard to do anything good for a better village life. As a first step, he insisted that Indians should unite to provide nation-building services to the village and not look to the State for doing what was our own duty towards our people. For him, this had to be the more important function of the Swaraj being sought from alien rule.

“In Rabindranath’s view, what had misled society in our transition to modernity was the introduction of the Western concepts of private property and material progress. What this led to was that mankind, though never free from greed, now crossed the limits, within which it was useful rather than harmful. What came about as a result was that property became individualistic and led to the abandoning of hospitality to our people and loss of communication with them. As a consequence, there was an increasing divide between city and village. He found all that to be the reality, when trying to bring about changes, both in his family’s agricultural estates and in the villages surrounding Santiniketan-Sriniketan.”

Tagore, Nandalal Bose & Leonard Elmhirst are together in this picture taken in 1924. Lord Elmhirst, then Tagore’s secretary/assistant stands at the back with Nandalal Bose between him and Gurudev. Courtesy: Creative Commons

To bridge this divide, Sriniketan was created with the involvement of more of the Tagore family, agriculturists, scientists from all over the world, like Leonard Elmhirst whom Tagore had invited in 1921 to lead the Sriniketan work, and artists, like Nandalal Bose. It was a path breaking experiment which found fruition in the long run. They adapted from multiple cultures without any nationalistic biases. Rathindranath brought batik from Indonesia into the leather craft of Sriniketan. We are told, “One of the early influences was from Santiniketan’s association with a group of creative thinkers from Asia, who were spearheading a Pan-Asian Movement that questioned Western hegemony in art and artistic expression. A pioneer of the Pan-Asian Movement was Kakuzo Okakura (1863–1913, Japanese scholar and author of The Book of Tea). He came to Calcutta in 1904, when he met Rabindranath, and they became friends. Okakura admired and supported Rabindranath’s Santiniketan school. Nandalal’s Kala-Bhavana syllabus included Okakura’s artistic principles of giving importance to nature, tradition, and creativity, which were the same as Rabindranath’s artistic principles.”

That Tagore’s effort was unique and overlooked by the mainstream is well brought out through the narrative which does not critique but only evidences. For instance, Das Gupta contends: “He (Tagore) wrote the same to Lord Irwin, the Viceroy, in a letter dated 28 February 1930, when appealing for a government grant towards agricultural research. ‘I hope I shall have the opportunity on my return for another talk with Your Excellency in regard to what has been my life’s work and in which I feel you take genuine personal interest.’ Lord Irwin had come for a visit to Sriniketan at the time and Rabindranath was told of his favourable impression of what he saw during his visit to Sriniketan. In his letter, Rabindranath wrote how he was doing the work ‘almost in isolation’, without any understanding from his people or from the government.” Does that often not continue to be the story of many NGOs?

Sriniketan by Dasgupta is a timely and very readable non-fiction which brings to light not just the humanitarian aspect of Tagore but the need for the world to wake up to the call of nature to unite as a species beyond borders created by humans and live in harmony with the Earth. It all adds up in the post-pandemic, climate-disaster threatened world. To survive, we could learn much from what is shared with us in this book. I would love to call it a survival manual towards a better future for mankind. Scholarship has found a way to connect with the needs of the real world. The book is reader friendly as Das Gupta writes fluently from the bottom of her heart of a felt need that is being voiced by modern thinkers and gurus like Harari — we need to bridge borders and unite to move forward.

Das Gupta retired as Professor, Social Sciences Division, Indian Statistical Institute. She was Head of the United States Educational Foundation in India for the Eastern Region. Recently, she has become a National Fellow of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study (IAAS), Shimla, and a Delegate of Oxford University Press. Her publications include Rabindranath Tagore: A Biography; The Oxford India Tagore: Selected Essays on Education and Nationalism; A Difficult Friendship: Letters of Rabindranath Tagore and Edward Thompson, 1913–1940; Friendships of ‘largeness and freedom’: Andrews, Tagore, and Gandhi, An Epistolary Account, 1912–1940. In this interview, she focusses mainly on her new book, A History of Sriniketan, while touching on how Tagore differed from others like Gandhi in his approach, his vision and enlightens us about a man who created a revolution in ideological and practical world, and yet remained unacknowledged for that as in posterity he continues to be perceived mainly as an intellectual, a poet and a writer.

Uma Das Gupta in the corridors of the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies (IIAS), Shimla, where she was visiting as a National Fellow (2012 – 2014) to advise on a permanent exhibit on Tagore’s life and work. The project was sponsored by the Ministry of Culture in celebration of Tagore’s 150th anniversary. This Institute is housed in the erstwhile Viceregal Lodge of imperial times. Photo provided by Uma Das Gupta

You are a well-known biographer of Tagore and have done extensive research on him. What made you put together A History of Sriniketan?

Grateful for your kind appreciation.

Writing a history of Sriniketan has been a priority for me. As a Tagore biographer, my dominant theme is about a poet who was an indefatigable man of action. His work at Sriniketan is of prime importance in that perspective. The secondary theme is of him as a poet and writer of many a genre, lyric, poetry, narratives, short stories, novels and plays. I had to make a choice of emphasis between the two themes since I did not intend to write a full-scale biography covering all aspects of Tagore’s life, equally. My choice was to explore his educational ideas and to examine how he implemented them at his Santiniketan and Sriniketan institutions. His work as an educator and rural reformer is even today hardly known because his genius as a poet and a song writer overshadowed his work as an educator, rural reformer, and institutional builder. That area of research was quite virgin when I started it as a post-doctoral project in the mid-1970s. For perceptions about his poetry and his large oeuvre I have drawn on the work of the scholars who know the subject better than I do.

My focus is on the concerns that featured persistently in Tagore’s writings and his actions. These were about the alienation in our own society between the elite and the masses, about race conflict and the absence of unity in our society, India’s history, nationalism, national self-respect, internationalism, an alternative education, religion, and humanism as elaborated by him in his collection of essays titled The Religion of Man (1931).

A History of Sriniketan is a detailed presentation about his ideas and his work on rural reconstruction. The idea of doing something to redeem neglected villages came to him when he first went to live in his family’s agricultural estates in East Bengal. His father sent him as manager in 1889. The decade that he spent there was his first exposure to the impoverished countryside. He was then thirty, already a poet of fame, and had lived only in the city till then. The experience played a seminal part in turning him into a humanist and a man of action. The closer he felt to the masses of his society the further he moved from his own class who were indifferent to the masses. His independent thinking gave him the courage of conviction to work alone with his ideas of ‘constructive swadeshi’.

As a pragmatist he knew there was not a lot he could do given his meagre resources as an individual in relation to the enormity of the needs. But he was determined at least to make a beginning with the work. His goals were a revitalized peasantry, village self-reliance through small scale enterprises, cottage industries and cooperative values. He wrote, “If we could free even one village from the shackles of helplessness and ignorance, an ideal for the whole of India would be established…Let a few villages be rebuilt in this way, and I shall say they are my India. That is the way to discover the true India.”

Disillusioned with nationalist politics he turned to his own responses to the many troubled questions of his times. Tagore was convinced there could be no real political progress until social injustices were removed. He pointed repeatedly to the sectarian elements of Indian nationalism which kept our people divided. He hoped that the Santiniketan-Sriniketan education would create a new Indian personality to show the way out of the conflict of communities. He thus brought a different dimension to nationalism by arguing for universal humanity. It led to doubts about his ‘Indianness’ among his contemporaries. He had the courage to defy the idea of rejecting the world as a condition for being ‘Indian’. In fact, he tried continuously to break out of the isolation imposed on his country by colonial rule. He had the foresight to sense that the awakening of India was bound to be a part of the awakening of the world.

What is the kind of research that went in into the making of this book? What got you interested in Tagore in the first place?

I am a historian by training. Historians have to back up every statement they make in their analysis by written documents. That is why the historian’s main source is the archives. Likewise, my research for this book has been mainly archival. I searched for written documentation from 1922 when the Sriniketan scheme of rural reconstruction work was officially launched. The documentation included the minutes of meetings, memoranda exchanged among the workers of the Institute of Rural Reconstruction, official notes, and annual reports written and filed.

In addition, I used to visit the villages in which the scheme was implemented to get an understanding of the ground reality. The work was started with six villages in 1922, extended to twenty-two more villages in the first ten years, and to many more villages afterwards. When the work was being run on a small scale, the Institute tried to post a village worker to stay in the village itself and work along with the villagers to implement the Sriniketan scheme. Some of these villages actually kept notes and records of their work which I could use as part of my local level research. I also interviewed some of the workers who had retired but who were still living around Sriniketan in their old age though their number was small. I have used those oral interviews in my documentation. Some of the Village Workers had their own private correspondence to which they gave me access.

There is also extensive personal correspondence in the Rabindra-Bhavana Archives between the leaders of the Sriniketan work. Among them first and foremost are Rathindranath Tagore and the British agricultural scientist, Leonard Elmhirst, whom Tagore had invited in 1921 to lead the Sriniketan work. Elmhirst had been to India earlier as a Wartime Volunteer during World War 1. When Tagore came to know of him through another British agriculturist working in Allahabad, Sam Higginbottom by name, he contacted Elmhirst with a request to come to Santiniketan and to lead the Sriniketan work. One of Tagore’s prime targets was to implement Scientific Agriculture in the villages. In fact, many years earlier, in 1906, he had sent his son Rathindranath and another student of the Santiniketan school, Santoshchandra Majumdar, who was Rathindranath’s classmate, to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne to study Agriculture with the view that they would bring back the expertise for the Sriniketan work at the completion of their studies.

Elmhirst was in Sriniketan from 1922 to 1924 after which he returned to his work in England. He worked closely with the Sriniketan team even from far through the letters they exchanged. Rathindranath consulted Elmhirst regularly over Sriniketan’s work in progress and this correspondence is in the archives.

There is also a very charming body of personal letters between Tagore and Elmhirst. Tagore’s originals are among the Elmhirst Papers in the Dartinghall Hall Trust archives in Devonshire, UK, and Elmhirst’s original letters are in the Rabindra-Bhavana archives, Santiniketan. This correspondence has been published.

Another very important source of documentation is available in the Diaries of Leonard Elmhirst which he wrote from the start of the Sriniketan work in 1922. Elmhirst’s Diaries were published by Visva-Bharati titled Poet and Plowman. There are some day-to-day accounts of how the work was being done on the ground by a group of senior students from Santiniketan who had chosen this field for training and of course by the Village Workers who had been appointed by the Institute. There were other leaders who helped with the work throughout like Kalimohan Ghose who later carried out the pioneering Surveys of the Villages. I have included some of these path breaking Surveys in the Appendices of A History of Sriniketan.

Last but not the least important for my research were Tagore’s ideas of education and rural reconstruction about which he wrote several essays in two important collections, namely Palli-Prakriti (Countryside and Nature) and Sikshya (Education). Some of the essays were autobiographical as to how he started the rural work in his family’s agricultural estates in East Bengal where his father sent him in 1889. He stayed at Selidaha, the Estates’ headquarters, with his family till 1900 when he moved to Santiniketan in South Bengal’s Birbhum district where his father had founded an ashram and called it Santiniketan, the ‘Abode of Peace’. It was not a monastic ashram but one for householders to spend some days in prayer and meditation away from their household responsibilities. This is where Tagore and his young family moved in 1900-01 with his plans to start a school for children in the heart of nature. It was to be a school where the children could learn to creatively assimilate the knowledge imparted to them instead of in the classroom that characterised colonial education. This was how his Santiniketan school was founded in 1901.

Santiniketan was located within two miles of the Bolpur Railway Station on the East Indian Railway Line. It was situated on high ground, in the middle of a wide plain, open to the horizon on all sides. There, father and son had planted noble groves of mainly mango and sal trees. There, in the heart of nature not far from a big city, Tagore had the advantage of being able to draw upon both raw materials and cultural products in equal measure as it were. There was the influence of trees, open fields, and the seasons changing so starkly on the one hand; on the other hand, there was the inspiration of artists, science teachers, libraries, and hand-made, machine-made, equipment.

You ask why I got interested in working on Tagore. There is a very personal story to share. When our son was born in Oxford where my husband and I were working with University Fellowships during 1972-73, we decided to move to Visva-Bharati on an invitation from the then Vice-Chancellor, the eminent historian Pratul Chandra Gupta. We were of course attracted to the possibility of being at Tagore’s institution and also to the prospect of raising our child in its pastoral environment. We did thus move to Visva-Bharati in 1973 leaving our Calcutta jobs at Presidency College, where my husband was Professor of History, and Jadavpur University, where I was teaching. Once we went Visva-Bharati, I began to explore the possibility of doing post-doctoral research on Tagore rather than on colonial history as was the area of my doctoral dissertation at the University of Oxford.

What would be the purpose of such a book? Do you think Tagore’s model would work if multiple NGOs adopted his ideas?

As I have already mentioned I am a biographer of Tagore’s educational ideas and the history of his institutions at Santiniketan and Sriniketan. To me writing this book on a history of Sriniketan was an integral part of my research. But at a personal level, I was concerned that the history of that practical and experimental work that Tagore did under the most difficult of circumstances might get completely forgotten if it were not documented. That was a genuine concern because of two reasons. Firstly, while Santiniketan has retained its charm as a popular tourist spot, and as Santiniketan’s oldest buildings of exceptional architecture had become heritage buildings, Sriniketan did not have anything to show or display for outsiders to connect with its one-time strident presence in bringing life and action to the villages. Secondly, Sriniketan never reinvented the wheel but just carried on from the 1950s as a unit of Visva-Bharati University to fill in for routine bureaucratic and funding purposes. Even its beautiful and thriving craft work that brought acclaim to Sriniketan from well beyond its precincts, would slowly but surely erode.

Therefore, the primary purpose of this book is to document a pioneering humanistic enterprise for posterity, and also for the next generations who were expected to be engaged in the field of rural development even though the original model was not necessarily practically and theoretically viable in today’s socio-economic scenario. The book is also for the scholar and for the generally interested person. When I was starting my work in the mid 1970s, there was no doubt in my mind that Sriniketan was becoming less visible.

As for whether multiple NGOs could use the Tagore model is for the NGOs to tell us, but I do know that in its neighbourhood, Sriniketan remains an important inspiration for mobilizing villages non-politically. There have been one or two such movements in the vicinity of Santiniketan-Sriniketan which are continuing to work actively at grassroots. One is Pannalal Das Gupta’s ‘Tagore Society for Rural Development’. Founded in 1969-70 as a registered society, the Tagore Society specialises in motivating villagers to take on environmental self-help projects. There is also the ‘Amar Kutir Society for Rural Develoment’ located very close to Sriniketan which was once a shelter for runaway political prisoners. Founded in 1923 by Susen Mukhopadhyaya, a young revolutionary freedom fighter then, who was attracted to Tagore’s work in rural reconstruction. We learn from his writing that he kept observing the work while coming in and out of jail himself. ‘Amar Kutir’ developed the work of organising local crafts persons, upgrading their skills, training them in design, and in marketing their products for economic rehabilitation. The Birbhum district had several families of traditional weavers. Some of them had been engaged in trade by the East India Company.

Another such non-governmental private initiative for rural development has come up more recently in 1984 in the outskirts of Sriniketan called the ‘Elmhirst Institute of Community Studies’, (EICS), whose members are working mainly in the areas of women and child development including family counselling, family adoption, de-addiction and rehabilitation, HIV/AIDS education and intervention. They were started with substantial moral and financial support from Elmhirst who was interested in spreading Sriniketan’s pioneering enterprise and taking the ideas further to meet the needs of the later day.

In other parts of India individual leaders were drawn to the work of building village self-reliance and a few had dedicated themselves to the cause in post-independence India. For his Ashrams at Sabarmati and Wardha, Gandhi himself kept closely in touch with Sriniketan which he visited several times even after Tagore’s passing and knew it well. Gandhi’s follower, Baba Amte, in Madhya Pradesh was a key worker in the field. More contemporarily one reads of the utopian commune ‘Timbaktu Collective’ in rural Andhra Pradesh where a husband-and-wife team, Bablu and Mary Ganguly, have organised the hapless farm labourers of Anantapur district to work for the regeneration of wasteland and start projects on organic farming, soil conservation, propagation of traditional food crops and have also taken steps for women’s and Dalit empowerment and rural health. Most of these ideas were at one time born and nurtured in the holistic laboratory for socio-economic development that Sriniketan was. Bablu Ganguly acknowledges Fukuoka as his mentor. Being Bengali by birth, it would not be surprising if he was aware of Tagore but perhaps only as a poet and songwriter.

Tagore withdrew from the national movement to develop villages, which is where, he felt lived a large part of India. Gandhi had a similar outlook. So, where was the divide?

With his deepening sympathy for the suffering millions of his country, Tagore became increasingly critical of the changes that Britain had brought to India. But he also felt strongly for the West’s ideas of humanism and believed they were of benefit to Indian society. Revolutionary changes were inescapably entering into our thoughts and actions. This was evident in the proposition that those whom our society decreed to be ‘untouchables’ should be given the right to enter temples. The orthodox continued to justify their non-entry into temples on scriptural pretexts, but such advocacy was being challenged and resisted. The people’s ‘voice’ had put out the message that neither the scriptures nor tradition nor the force of personality could set a wrong right. Ethics alone could do so.

There were important factors that led gradually to this new way of thinking. The impact of English literature was one such. Tagore pointed out that acquaintance with English Literature gave us not only a new wealth of emotion but also the will to break man’s tyranny over man. This was a novel point of view. The lowly in our society had taken it for granted that their birth and the fruits of their past actions could never be disowned; that their sufferings and the indignities of an inferior status had to be meekly accepted; that their lot could change only after a possible rebirth. Society’s patriarchs also held out no hope for the downtrodden. But contact with Europe became a wake-up call. It was no surprise that in his landmark essay Kalantar (Epoch’s End) Tagore recalled and endorsed the British poet Robert Burns’s unforgettable line, “A man’s a man for a’ that”.

It was in that longing to bring hope to the deprived people that Tagore and Gandhi felt really close. They were both carrying out rural reconstruction work because they knew that the majority of Indians lived in villages and wanted to bring awakening and national consciousness to the villages as the prime goal to freedom. Both men focused their attention on the peasantry as the largest class within Indian society who were paralysed by anachronistic traditions and weighed down by poverty and the absence of education.

The major issues on which Tagore and Gandhi differed were debated nationally. Before discussing the specific issues in the controversy, it would be useful to examine their general positions on freedom and nationalism. In The Religion of Man (1931), Tagore developed the position that the history of the growth of freedom is the history of the “perfection of human relationship”. Gandhi applied the same principle to resolving India’s racial conflict. Tagore took the idea further and challenged the credo of nationalism. Tagore argued that the basis of the nation-state was a menace to the ideal of universal harmony or to the “perfection of human relationship”. But to the nationalist leadership all over the country, including Gandhi, political self-rule or swaraj came to be understood as a necessary phase of spiritual self-rule, or swarajya, and nationalism as the first step towards attaining free human fellowship.

Tagore alone spoke out against that trend. He argued that the crucial stumbling block in India’s future lay in the social problems of the country such as the absence of human rights for the masses and the alienation between the educated classes and the masses. He emphasised what the country needed most of all was constructive work coming from within herself and the building of an ethical society as the best way for rousing national consciousness. The rest would inevitably follow, even political freedom.

In his novel, Ghare Baire (The Home and the World, 1916), Tagore seemed critical of Gandhi’s call for Khadi and burning of mill cloth imported from England. Yet, Sriniketan was a handicraft forum for villagers to find a way to earn a living through agriculture and craft. So, why the dichotomy of perspectives as both were promoting local ware? Where was the clash between Gandhi’s interpretation of Khadi and Tagore’s interpretation of selling indigenous craft?

There was never any conflict in their perceptions or feelings for the poor, Gandhi’s and Tagore’s. Other issues were stirred in relation to the Khadi campaign and the burning of foreign cloth. For instance, the Congress in 1924 moved a resolution under Gandhi’s recommendation enlisting its members to spin a certain quantity of cloth on the charka (spinning wheel) as a monthly contribution. The idea was to give the movement country-wide publicity, and also, to make spinning a means of bonding between the masses and the politicians.

Tagore was wholly opposed to the idea of using the charka as a political strategy for swaraj and explained his position in his 1925 essay titled ‘The Cult of the Charka’. He argued that there was no short-cut to reason and hard work if anything was to succeed; that nothing worthwhile was possible by mass conversion to an idea; that our poverty was a complex phenomenon which could not be solved by one particular application such as spinning and weaving Khadi. Tagore raised the question if our poverty was due to the “lack of sufficient thread”, or due to “our lack of vitality, our lack of unity”?

On burning clothes Tagore’s position was that such a method hurt the poor by forcing them to sacrifice even what little they obtained from selling those clothes. He concluded that buying and selling foreign cloth should be delegated to the realm of economics. In his reply Gandhi wrote, that he did not draw “a sharp or any distinction between economics and ethics”. He added that the economics that hurt the moral well-being of an individual or a nation “are immoral and therefore sinful”.

Is Sriniketan unique? Can it be seen as Tagore’s model for rural development?

To the best of my knowledge there is no parallel institution in India.

I am not aware if Tagore was ever talking of a ‘model’ that he expected others to follow. He was certainly hoping, as he wrote, that his work will help to establish an “ideal” [his word] for the rest of the country.

My own sense is that an “ideal” has been established given that empowerment of the villages through the Panchayats has become a nationwide project. Of course, the government’s approach is not fully in character with Tagore’s holistic vision for the individual’s humanistic development. Today the individual hardly counts, politics and economics are what matter. All the same it has to be said that the villages are getting some attention and are not left to rot as had been the case in the earlier century.

You have said that Tagore faced criticism for the way he used Nobel Prize money. Can you enlighten us on this issue? Tell us a bit about the controversy and Tagore’s responses.

As anyone would surmise the Nobel Prize money was very precious also to the Santiniketan community because the teachers and workers there had to struggle over the resources for the institution. But contrary to the community’s expectation, Tagore decided that the Prize money would be given to the cause of rural credit. He had started the Patisar Krishi (farmers’) Bank in 1906 followed by the Kaligram Krishi Bank. According to Tagore’s biographer, Prasanta Pal, the total investment in the rural banks in 1914 amounted to Rs 75,000 of which Rs 48,000 was invested in the Patisar Krishi Bank at 7% interest per annum and Rs 27,000 at the same rate of interest in the Kaligram Krishi Bank. Tagore decided that only the interest from those investments could be used to pay for the maintenance of the Santiniketan school. The actual purpose of the fund was to give loans to the poor peasants so as to relieve them from exploitation by moneylenders and some unethical landlords too. In order to repay their loans, the peasants had to sell their produce at a rate lower than the market price immediately after drawing the harvest. This phenomenon was causing them perpetual indebtedness. The Krishi Banks were to loan money to the peasantry at a lower rate than the money lenders and relieve them from the age-old exploitation.

Tagore was firm that the primary beneficiary of his Nobel Prize money would be the poor peasantry of his family’s estates, and the Santiniketan school would be only the secondary beneficiary. He tried thus to balance his two main concerns when settling the future of his Nobel Prize money.

It cannot be said there was a ‘controversy’ over this as Gurudev (which was how the community addressed Tagore) was too revered for a controversy to be raised about a decision that he had taken. But there was disappointment. It seemed strangely that even his inner circle had not realised his deep emotional attachment and ideological commitment to the cause of the impoverished peasantry. Perhaps, my response to your earlier question may explain why.

Tagore had noticed the gaps between the different strata of Indian society. Sriniketan was an attempt to bridge the gap. How far did his ideals succeed?

There was tremendous societal gap between the different strata of Indian society. With all of Tagore’s will and effort, it cannot be said that the Sriniketan ideals could bridge the gap. Even today, a perceptive visitor, who visits Santiniketan and Sriniketan, located only within two miles of each other, can tell the difference between the two. Santiniketan looks bright and thriving, but Sriniketan looks neglected.

Community life in the Indian villages was seen to break for the first time with the emergence of professional classes among the English-educated Indians. The city began to attract them away from the villages. Those Indians were happy to let the government take over guardianship of the people and relinquish to it their own traditional duties to society. The result was a widening gap between town and country, city and village. Tagore knew from his life’s direct experience that none of those who dominated the political scene in his time felt that the villagers ‘belonged’. The political leadership apprehended that recognising this vast multitude as their own people would force them to begin the real work of ‘constructive swadeshi’. They were not even interested to try. That was where the Sriniketan effort was invaluable to Tagore. He saw that the endeavour built at least a relationship with the village, if nothing else.

The Sriniketan scheme sought to bridge the gap by bringing to the village a combination of tradition and experiment. Tagore knew that a civilisation that comprises of only village life could not be sustained. “Rustic” was a synonym for the “mind’s narrowness”, he wrote. In modern times, the city had become the repository of knowledge. It was essential therefore for the village to cooperate with the city in accessing the new knowledge. One such vital area of expertise was in agriculture. His study of “other agricultural countries” had shown that land in those countries was made to yield twice or thrice by the use of science. A motor tractor was bought for Sriniketan in 1927 because he believed that the machine must find its way to the Indian village. He wrote, “If we can possess the science that gives power to this age, we may yet win, we may yet live.”

Your book tells us that Sugata Dasgupta’s publication, A Poet & A Plan (1962) showed that Sriniketan had benefitted the villages it adopted decades after Tagore’s death. Has there been further development of these communities or is it status quo?

No, it cannot be said that it is status quo from the 1960s. There have been changes for sure. There have been benefits to the villages from the Government’s projects. Indeed, the government had adopted some of their early projects from Sriniketan’s original work.

More interventions are needed of course but it has to be said something is being done. Of course, the changes I can mention that have benefitted the condition of the villages and therefore the villagers’ lives came well after Sugata Dasgupta’s publication. The three that I can mention are communications, roads, and electricity. Today there are more long-distance buses than ever before transporting people to and from the villages. Totos and cycle rickshaw-vans take passengers from the bus stands to the interior villages. Roads are another major development. Besides the highways, the mud paths in the villages are now being converted to metalled roads. There is electricity in the villages.

I should mention one other significant change which is that secondary education is now fairly common to the present-day rural populace. College education has also come within their reach.

What is the current state of the present day Sriniketan? What do you see as the future of Sriniketan?

Presently, Sriniketan runs as a department or unit of Visva-Bharati University and works according to the University’s requirements. I am not acquainted with the requirements. I continue to be a regular user of the University’s Rabindra-Bhavana archives even now. But I have not been connected with the University in any official capacity after the 1980s which is a long time ago.

Thank you for your time.

(This is an online interview conducted by Mitali Chakravarty.)

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL