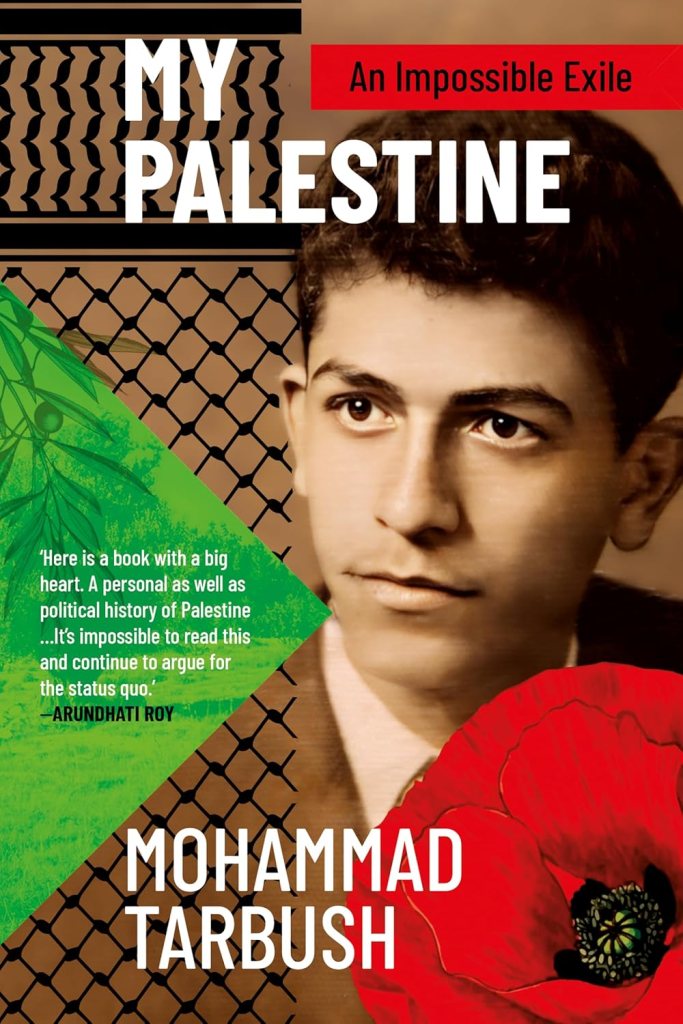

Title: Leonie’s Leap

Author: Marzia Pasini

Publisher: Atmosphere Press

“Son,” Hridaya whispered again, this time with an edge that made him quiver. “Do you know why you’re here?”

“I don’t,” Leonie answered, still shaken by his visions.

“Then I’ll tell you: this is your last incarnation. Your chance to break free from the cycles of separation and denial that have kept you bound. Do you know what this means?”

“I don’t,” he admitted.

Hridaya took a moment to adjust his robe, then gripped Leonie’s forearm, his voice low. “It means your ancient soul chose to return to this plane one last time for the purpose of liberation. Divine destiny is with you, but you still have the will to reject it. If you turn away, the universe will keep sending the lessons you need to learn. Ignore them, and they’ll get harsher. Do you understand?”

Leonie shrugged in resignation. “What does it matter what I’ve come here to learn?” he murmured, his gaze falling to the ground. “I’m all alone, anyway.”

“Nonsense,” Hridaya countered, his grip on Leonie’s palm firming.

“You are no orphan, but a beloved child of the universe. Though you may feel displaced, your soul is anchored to the womb of the world; your hands inter-twined with the pulse of creation. It is only in the folly of ignorance that we choose to desert ourselves, becoming orphans to our very own souls.

“Look,” he said, squinting his blind eyes as if sensing Leonie’s pain, “I know life doesn’t always add up the way we want it to, but that doesn’t mean we should stop counting our blessings. You see, there is no good or bad luck, really, only wisdom to be gained from our unmendable human condition.

“Our personal stories shape us, but they do not limit or define us. In the end, who we truly are escapes all form and definition. It doesn’t matter, then, what star you were born under or which side of the river you drank from— obstacles will arise either way. You must not get discouraged, son. We are here to pave the way for each other, learning to see clearer so we can love better.

The fortuneteller paused, as though listening for a distant whisper only he could hear. Then, with his head tilted toward the sky, he continued: “At any point, we can give our life a hundred different names or simply call it grace. It all depends on how well we learn to see through things. Sometimes the greatest trials turn out to be our highest blessings. Other times, we are left with indelible wounds, marks that cannot be erased or repaired. But if we carry our hurt with grace, the scars stitched onto our skin become luminous constellations guiding our way home.

“Now happiness is the common road. But freedom? Here the road forks. The path of freedom is not the way of the masses, nor the aspiration of the tribe. Many of us meddle with freedom, but freedom has little to do with getting things our way, possessing what we desire, or feeling good about this or that.

“Before we’re born, freedom is woven into the fabric of our souls. As children, we understand this instinctively, but as we grow, this knowingness fades, leaving us nostalgic or in denial. Only a rare, disgruntled minority set off on a quest to reclaim what’s been lost. Some journey far, sometimes to the farthest edges of the earth. Don’t get me wrong. At times, the search is required. Yet what really matters is never the distance we travel, but how deep we are willing to dive to illuminate the shadows.”

“Son,” the fortuneteller leaned in, his voice dropping to a secretive whisper. “You’ll hear many promising you something better or more. It seems to me everyone hopes to hoard magic, but the pot of gold doesn’t just sit at the end of the rainbow. Treasures pepper the trail. Each day, the path unfolds, ever unwritten. Now tell me, what does your heart long to know more than anything so it may be made free again?”

Silence pervaded the forest once more. A gentle breeze brushed against Leonie’s face as he gazed out at the water, then back at the man. “The truth about my mother,” he uttered. “That is what I’d like to know most.”

Hridaya sighed deeply. “The truth, son, will set you free, but to do so, it must break open your heart first. Are you sure this is what you want to know more than anything?”

A tremor rippled through Leonie’s heart. He knew that the truth, whatever it was, would hit like a punch to his chest.

***

Dearheart, perhaps you, too, have felt the sudden whack of truth—a force you have avoided, fearing it could shatter the world as you know it. Be honest: how often have you told a white lie to help someone save face or feel better? How many times has something inside you desperately wanted to live out the truth, and at the same time hoped it would never be revealed?

There’s no escaping it: the truth is seldom subtle. It’s a hurricane, exposing what you’ve kept covered. If we let the truth be destructive, it will wreak havoc. Yet honesty doesn’t have to be crushing; it can be as gentle as blushing. Gentle honesty is wise and discerning. It doesn’t weaken relationships; it deepens them. Speaking the truth is never about being rude, harsh, or unfiltered—it’s about upholding integrity in the centre of your heart. After all, honesty is a prickly rose. It must be handled with care, carried with grace, and delivered with unbending kindness. Even if it’s tough, lean into the hard conversations softly and speak your heart boldly. Stand for the truth—whatever the cost. Anything less is fickle, unreliable, and untrustworthy.

Dearheart, have you ever wondered about that tingle keeping you awake at night? Where does the fiery inspiration spark from? Why does your soul beckon you in? Consciousness is ever awake, whether you are asleep, stumbling, or taking the leap. It patiently waits for you to unlock the mysteries of your spirit and embrace the liberating journey that awaits.

About the Book

Leonie’s Leap tells of the adventures of a fifteen-year-old orphaned acrobat who escapes his dreary life to join the circus as a trapeze artist. Just as the daring acrobat takes the bold plunge into the unknown, your inner exploration reveals the hidden wonders within.

Your capacity to return to this wild inner landscape is the answer to your deepest longing, the home where every prayer settles. It doesn’t matter where you come from or what path you have chosen—every bit of YOU knows it: you were born to live vibrantly from your depths. The world needs you to dwell in your wildly liberated heart. It breathes through your sacred dreams. Your wings. Your feet.

Are you ready to leap?

About the Author

Marzia Pasini is a writer and life coach devoted to heart consciousness and the sacred return to self. With a background in Philosophy and a Master’s in Comparative Politics from the London School of Economics, she began her career in international development, working with the United Nations and the Office of Her Majesty Queen Rania of Jordan. Two life-altering health crises sparked a profound inner shift, inspiring her to help others reconnect with their inner freedom and truth. She has also authored a children’s book Satya and the Sun, which follows a young girl on a magical journey through her fear of the dark—offering an empowering reflection on change, trust, and the unknown.

Originally from Italy, Marzia has lived in six countries and now makes her home in India with her husband and two children.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International