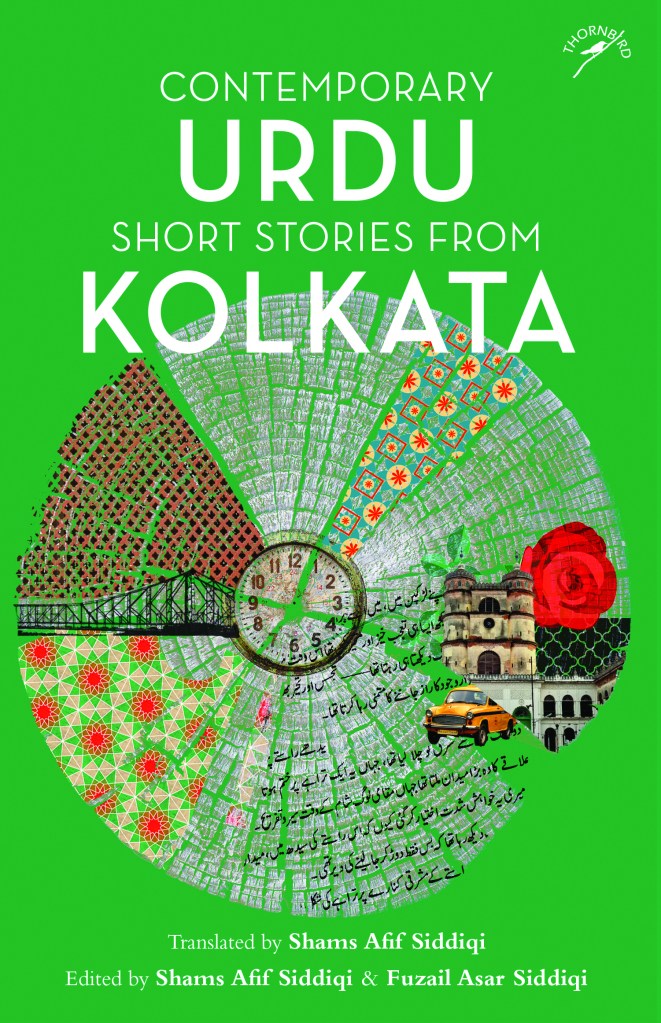

Title: Contemporary Urdu Stories from Kolkata

Authors: Sayeed Premi, Firoz Abid, Anis Rafi Siddique Alam, Mahmoud Yasien, Shahira Masroor Anisun Nabi, Reyaz Danish

Translated by Shams Afif Siddiqi, edited by Shams Afif Siddiqi and Fuzail Asar Siddiqi

Publisher: Niyogi Books

The Stopped Clock

By Siddique Alam

The hands of the clock had stopped permanently at 13 past two and two seconds. Sitting on the bench under the shed, I am trying to understand the oval dial of the clock, the Roman letters of which had become dimmed and its edges covered with spider webs. I wonder when the clock might have stopped. I am 35 years old. Is there apparently any difference between us? Just like the clock, I have also stopped for a while because there was no announcement about the arrival of my train, its departure time being four hours ago.

I am trying to survey the place with wide open eyes. It is a usual day and an ordinary station that we are accustomed to see.

I have bid farewell to the city of my birth. I am leaving the city like a failure. But it seems after relinquishing me, the city, with a feeling of guilt, now wants to take me back. Its first step in this direction is to delay my train for an indefinite amount of time.

Despite being in the midst of a city, a station is free from its clutches. I am enjoying that freedom with a one-way ticket in my pocket. A bit of patience, I tell myself, and I would be far away. Nobody can stop me, neither by erecting obstacles in the way of the railway tracks nor by stopping the hands of the clock. Maybe I am a loser, but the journey of my life is yet to end. I am only 35 years old. I have to go far away from this place. The most important thing is that I am satisfied that the address I am carrying in my pocket is not my last destination.

It is a temporary waiting place that can help me make a new beginning. After all man is born free. The sun does not select a particular spot to shine, nor is every wave that dashes against the shore the last one, losing which the boatman would have to wait all his life for another wave.

An old coolie, wringing khaini[1] in the palms of his hands, passes by me. He is clad in a white banian and dhoti, his red flannel shirt thrown on his left shoulder.

‘Since when has the clock stopped?’ My question stops him in his stride. He turns around, his tired, thoughtful eyes staring at me. A sense of shame overpowers me. He may be an illiterate coolie, not a station employee who is answerable for such a question. ‘I am sorry,’ I quickly add, ‘I should not have put the question to you. I take back my words.’

‘Why sir?’ he stands by the side of the bench, and looks at me with a sense of intimacy. ‘People will be asking questions about a stopped clock, isn’t it? They cannot to be blamed. The story of the stopped clock is well known but only the signal man Gocharan Ray has the right to tell its tale. He had spent all his life showing green and red flags to trains and has retired today.’

‘Who has replaced him?’ my question betrays my foolishness. My imprudence had always entangled me in thoughtless acts.

‘Why don’t you ask the station master?’ The coolie moves away. ‘It’s a question that requires an answer; otherwise, you will regret it all your life.’

I was not ready for such an unexpected turn of events. I thought that my relationship with the city had been cut off forever. What do I make of a station that has ignored me, as if the ticket in my pocket is of no worth? Once again, I look at the dial of the clock hanging from the shed. It had stopped at 13 past two and two seconds. What might have happened when it stopped? Did an accident take place at the station? Had any incident of murder taken place? Was it at the time of the departure or arrival of an important leader? An attack by Naxalites? Or was the place the site of a communal incident?

The coolie returned again. This time he was wearing his shirt. ‘Unless you hear the story,’ he says, ‘your train will not arrive. This is the rule here. It may take weeks, months, or even years and you have to move from one platform to another with your suitcase. Once, a passenger alighted here to board another train. He faced a similar dilemma. He asked the same question about the clock but I do not know what happened and why he refused to listen to the story. Do you know what happened to him?’

‘How can I?’ I replied impatiently. ‘The city hardly gave me any time so that I could listen to stories.’

‘You are becoming irritated unnecessarily, Sir,’ he said. ‘I want to tell you about the man. The fact is nobody knows much about him. Some say he went to the city and did not return. Others say he took another train that never reached its destination. Some may even tell you that a prostitute took him to her house by the railway tracks where he developed leprosy and is slowly dying there. There is also no dearth of people who say he is still moving, suitcase in hand, amidst platforms, difficult to spot in the teeming crowd of passengers.’

‘You mean to say he can be anyone, even me?’

‘Did I say that, sir?’ He was on the verge of leaving. ‘It seems you have tasted bitter gourd.’

I was staring at the departing coolie’s back. The constant use of the flannel shirt had not only exposed its fibres, it had also thinned the material exposing the bones of the man’s neck. I have no hesitation in saying that I did not believe him. Since the time when suitcases developed wheels, the number of coolies has dwindled in stations. The last nail was the introduction of the backpack. Either passengers drag their suitcases on wheels, or carry luggage in their backpacks, leaving the coolies with little work. So, this may be their way of passing time.

About the Book

Dealing with love and loss, dreams and reality, as well as history and violence, this is a collection of best 19 short stories that encompasses the whole gamut of human experience, seen through the eyes of current Urdu writers from Kolkata.

Stories from Kolkata are often assumed to be about bhadralok culture and the Bengali way of life. But Kolkata is a city with amultiplicity of stories to share. Contemporary Urdu Short Stories from Kolkata highlights the diversity of recent Urdu short stories fromthe city. In one of these stories, a writer trying to escape the city wants to find the reason why the railway clock has stopped working, in another, a new friendship sours as soon as it blossoms, while some other stories show how the complexity of human relationships is explored. There is an experiment in abstraction, and legend and reality are brought together when three sleepers of an earlier civilization wake up in the modern world.

About the Editor and Translator

Shams Afif Siddiqi, former Associate Professor of English (WBES), author, short story writer, and literary critic, was born in 1955 in Kolkata. He taught in government colleges of West Bengal for 35 years and was a faculty member at MDI, Murshidabad. Khushwant Singh selected his short story for publication in The Telegraph in the 1980s. His publications include The Language of Love and other Stories (2001), a critical look at Graham Greene’s novels, Graham Greene: The Serious Entertainer (2008), and an annotated edition of G.B. Shaw’s Arms and the Man (2009).

Fuzail Asar Siddiqi is currently a PhD candidate at CES, JNU, New Delhi, researching on the modernist Urdu short story, in general, and short stories of Naiyer Masud in particular. The founder/editor-in-chief of an academic editorial services company, he has been an Assistant Professor of English at Gargi College, New Delhi.

[1] Khaini: Tobacco

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL