By Ratnottama Sengupta

The Gregorian calendar was still showing 1998.

I was in Oxford on a Charles Wallace fellowship to study John Ruskin’s influence on M K Gandhi and R N Tagore. Like any other student I lived in a hostel, walked up to the Ruskin School of Art and Ashmolean Museum, to the High Street and the flea market, to the Bodleian Library, and – of course – the book stores that continue to make that ancient city of academic excellence such a delight for a person like me who started crawling in the midst of books.

What caught my fancy on the book-lined shelves in the hometown of a ‘legal deposit’ library? The screenplays of Quentin Tarantino. Countless books on Elizabeth 1 – perhaps because Shekhar Kapur’s Elizabeth had just released worldwide. And the volumes on art. The gorgeous reproductions halved the tedium of walking miles of museums and galleries. And the history of art rekindled my love for paintings from our collective past.

But what I didn’t take kindly to was the neglect of – if not bias against — art from my homeland. There were books on Greek, Chinese, Japanese , African, Egyptian, Mayan, Roman art, on Russian Icons and Stained Glass windows, on French Impressionists and German Expressionists, Cubists and Moderns… But Indian art? For crying out loud, where was Ajanta-Ellora? The glass paintings and Miniatures? Pichwai and Patachitra, Nathdwara and Kalighat Pat, Warli and Madhubani, Santiniketan and Baroda?

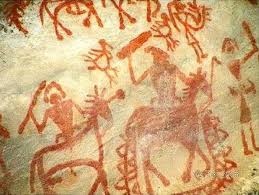

That’s when I told myself, “Put the journey of Indian paintings between covers.” For, which other country has a continuity that I can boast, of a tradition that has continued unchequered for three thousand years and more?

Once I was back home, my friend Reeta Dutta Gupta approached me to edit an Encyclopedia of Culture for the India Series she was nursing. And Dr Jain of Ratna Sagar entrusted me to author a Notebook that would recount for school-going children the story of Indian art from Bhimbetka to the present millennia. What luck!

*

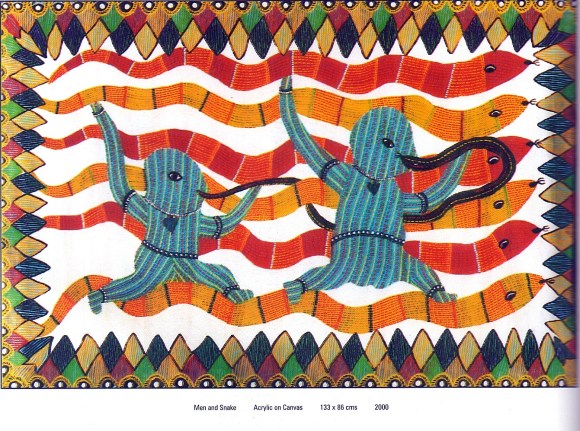

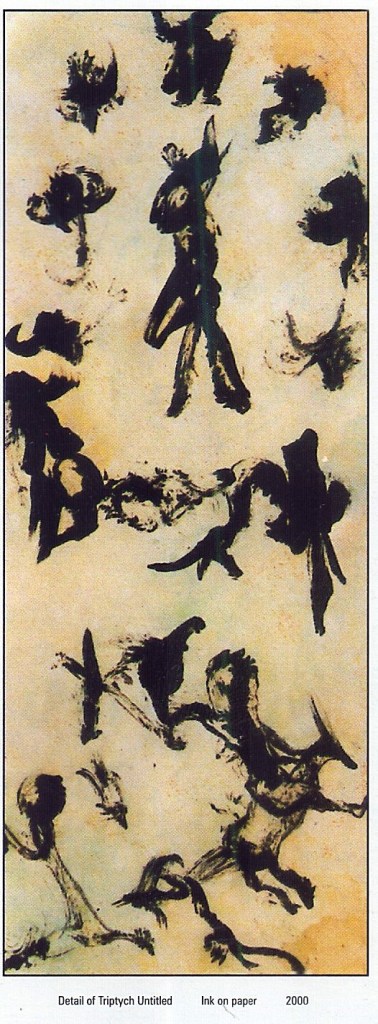

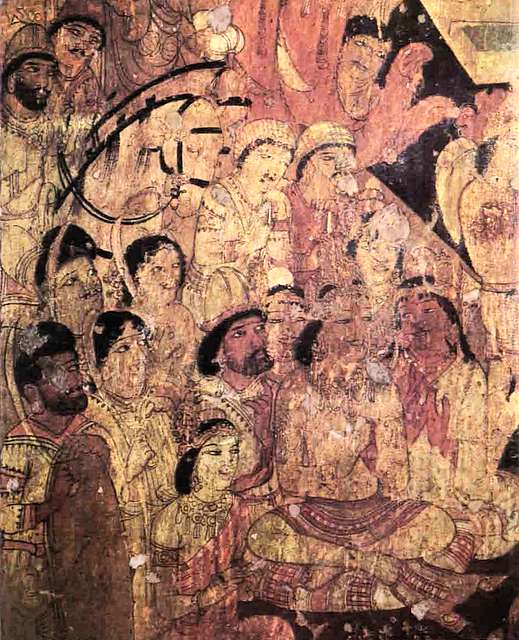

Be it the hunters and the hunted of Bhimbetka, the rock art now on the UNESCO list of World Heritage, or Kolam and Alpana and Rangoli, the decorative designs of Kerala and Bengal and Maharashtra. Be it the Buddha of Ajanta Frescoes or the ploughmen and blacksmith of the Haripura Congress panels painted by the Bengal master Nandalal Bose, be it the illuminations in the Jain manuscripts or the Mughal manners immortalised by the kalams: art in India has grown out of everyday life. These art expressions have been an integral part of the people’s existence, regardless of the style or the period in which they were painted. Yes, down centuries Indian art has withstood change of regiments, religions, philosophy, social content, historical setbacks. And, aesthetic excellence has found an outlet in forms and lines, strokes and colours, whether these were obtained by crushing gems or pounded rice.

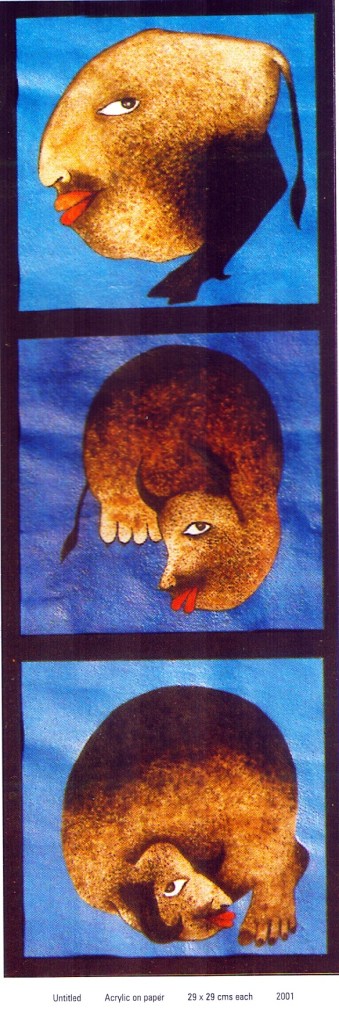

This has helped India enjoy a continuity that is rare even in the developed societies. From the sketches of Bhimbetka to those of the tribal artists of Warli, from the murals of ancient India to the art of contemporary masters, from the miniaturised figures to the Tantric patterns – art in India has reinvented itself again and again. And each time it has emerged with renewed vigour and vitality. Because, every age has related to art in an intimate way. By painting on the wall. Decorating the floor. Placing it on the altar. Or simply by keeping an account of the times.

As A Ramachandran – then professor of art at Jamia Millia Islamia in Delhi – had said to me, “Even when our ancient language that was deemed the language of the gods, fell into oblivion, art transcended centuries because it was communicating through a universal language – the visual language of colours and hues.” The lines defined the form, and also created a unitary area for the use of colour, he had further explained. “No matter what the subject, comprehension was never a problem for the Indian – until he was confronted by the art that was imposed by the colonialists.”

The Western overemphasis on realism played havoc, with the native sensibility that allowed for imagination and stylization, Nair Sir had pointed out. That sensibility had no problem accepting a ten-armed goddess, Dasabhuja Durga, or Dasanan, the ten-headed Ravan. “Lifestyle changes too have led to the dilution of Indian aesthetics that once enveloped our workaday lives. The only living art today is the visual art traditions in the villages, but that too might not last as villagers now want to ‘rise’ to the level of the urbans!” he had lamented.

In such a situation, art becomes doubly significant in the life of a child. When she or he is exposed to it, the child can not only access the history and the continuity of a culture but also nurture it with love that can ensure it lives in the days to come… With this in mind, I will write to focus on the high points of Indian art.

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and writes books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International