Keith Lyons in conversation with Harry Ricketts, a writer and mentor who found himself across continents and oceans

Harry Ricketts is a New Zealand poet, essayist, and literary biographer whose work has gained recognition for its wit, lyricism, and insight into memory, identity, and everyday life. He has published widely across poetry, biography, and literary criticism, and his writing blends formal elegance with accessibility. After studying at Oxford University, he taught in the UK and Hong Kong before moving to New Zealand in the early 1980s. A respected teacher and mentor, Ricketts has shaped both the literary culture of New Zealand and the broader English-language literary world through his poetry, essays, and guidance to emerging writers. His works include a major biography of the British India-born journalist, novelist, poet, and short-story writer Rudyard Kipling, The Unforgiving Minute, Strange Meetings: The Poets of the Great War, and his most recent books, the memoir First Things, and the poetry collection Bonfires on the Ice. His How to Live Elsewhere (2004) is one of twelve titles in the Montana Estates essay series published by Four Winds Press. The press was established by Lloyd Jones to encourage and develop the essay genre in New Zealand. In his essay, Ricketts reflects on his move from England to New Zealand. In this interview, he brings to us not only on his writerly life but also his journey as a mentor for other writers.

KL: Tell us about your early life?

HR: My father was a British army officer, and we moved every two years till I was ten: England, Malaysia, two different parts of England, Hong Kong, England. My first words were probably Malay. From eight to eighteen, I went to boarding schools in England; apart from the cricket and one or two teachers, this was not a positive experience.

KL: How do you think moving around affected you, and your sense of self and being in the world? Does that transience shape your perspective and writing now?

HR: I think constantly moving around gave me a very equivocal sense of belonging anywhere and also a strong sense of needing to adapt (up to a point) to wherever I found myself. I was an only child, and friendship became and remains incredibly important to me. Perhaps this hard-wired sense of temporariness has contributed to my trying to produce as many different kinds of books as possible, but eventually you discover what you can and can’t do: I can’t write novels.

KL: How has your sense of ‘home’ evolved in your work over the years?

HR: As above, but I’ve lived in New Zealand for more than forty years, so that must count for something. My second wife, Belinda, was a Kiwi; for thirty years, she was a lovely person to share the world with. I’d say I like to live slightly at an angle to whatever community I’m in.

KL: How did books and poems come into your life, and what do you think have been influences on your later work?

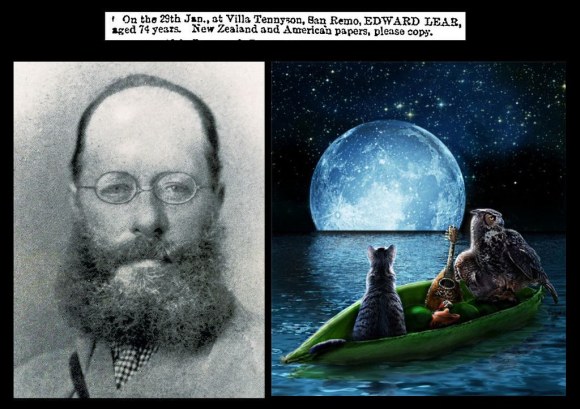

HR: My mother was a great reader and read me Beatrix Potter, A.A. Milne etc as a child. When I was seven, I had measles and had to stay in bed for a fortnight. I read Arthur Ransome’s Peter Duck and then I couldn’t stop. Books were a protection and a passion at boarding school. As for poetry, at school we had to learn poems by heart which I enjoyed and later recited them in class which was nerve-wracking. When I was fifteen – like many others – I fell in love with Keats, then a few years later it was Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes, T.S. Eliot, Gerard Manley Hopkins, C.P. Cavafy ….. I was also listening to a lot of music, particularly singer songwriters like Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Richard Thompson, Joni Mitchell.

Everything you read and listen to is an influence. My mind is a lumber-room of things I’ve read and listened to, things other people have said, things that have happened to me and to others, places I’ve been, love and friendship – and all that crops up in my poems in one way or another. Plath and Hughes were a wrong trail. It took me a while to work that out. Well into my twenties, I couldn’t stand Philip Larkin, but not now. I like witty, melancholy poets.

KL: Your first book, People Like Us: Sketches of Hong Kong was published when you were 27. How did that come about.? What satisfaction did you get from seeing your name in print?

HR: People Like Us is a mixture of short stories and song lyrics. Hong Kong, as I experienced it in the 1970s, (still very much a British colony) was a heterogeneous mishmash of styles, and I tried to mimic that mishmash in the pieces I wrote. I was pleased when it got published but it wasn’t much good.

KL: Can you describe your writing space?

HR: I have a small study, but since Belinda died two years ago, I’ve shifted to the kitchen table. She wouldn’t have approved, but the kitchen is light and airy and the stove-top coffee-maker close by.

KL: What is your writing process from start to finish?

HR: I do a lot of drafts. First thoughts can almost always be improved. A friend likes to say, ‘It’s not the writing; it’s the rewriting’, and I agree. But some poems have come quite quickly. When I’m writing prose, I often play music, but not when I’m working on a poem.

KL: What usually sparks a new poem for you: an image, a phrase, or a rhythm?

HR: It can be anything really. I’m usually doing something else entirely – writing an email or some piece of prose or just walking around – and something will interrupt me. It’s often a phrase which for some reason acts like a magnet, attracting another phrase or an images or an idea. It might be something I’m reading; this has happened with English poets like Edward Thomas, Philip Larkin, James Fenton, Hugo Williams and Wendy Cope and New Zealand poets like Bill Manhire, Fleur Adcock and Nick Ascroft. Occasionally, I’ve written a commissioned poem: for a friend’s wedding, say.

KL: How do you balance experimentation with accessibility in your work?

HR: I don’t think like that, but I do try not to repeat myself if I can help it. However, several poems of mine have had successors; so I wrote a poem in the mid-1980s about my six-year-old daughter Jessie called ‘Your Secret Life’, imagining her as a teenager and me waiting up late for her to return home, and my latest collection contains a ‘Your Secret Life 5’, written when she was forty. I’ve found myself writing a few poem-sequences recently, including one about an imaginary New Zealand woman poet. That was quite new for me.

KL: How do your roles as poet, biographer, and critic feed into each other?

HR: Constructively, I hope. I think you can always get prose out of yourself if you sit there long enough (fiction writers might disagree), but not poems. Some initial reverberation/interruption has to happen, some ‘spark’, as you put it. It’s all writing, of course, and writing is a habit. You have to keep doing it, otherwise that part of you switches itself off or attends to other things.

KL: Looking back across more than thirty books, what evolution do you see in your writing life, and what themes do you keep on coming back to?

HR: I think lots of writers (except the very vain ones) suffer from versions of ‘imposter syndrome’ and have problems with their personal myth — that they are a writer. I’ve got a bit more confident that I am a writer and in particular that I can write poems. Getting published helps a lot with the personal myth: something you’ve done is now out in the world. Once you publish a book, though, you lose any control you had over it. People may love it, hate or, worst of all, ignore it. But that’s just the deal.

I prefer the term preoccupations to themes. I’m preoccupied with people, places, trying to make sense of the past, happiness, the role of luck, life’s oddities, incongruities and ambiguities….

KL: You often talk about ‘gaps’, doubt, and ambiguity as central to your work. How do these function in your poetry today?

HR: To measure gaps, to be in doubt, to see the ambiguity in things: that just seems to me to be human. Poems can be acts of discovery or at least partial clarification. They can also simply preserve something: an experience, a moment, a realisation, some sense of those we love.

KL: You describe teaching as a kind of midwifery: helping writers bring out what is already within them. How did you arrive at that approach?

HR: Decades of teaching suggest to me that encouragement is more likely to help someone tell the stories they have it in them to tell rather than giving them a hard time. Writing can be a bit like giving birth and, for some, having support and encouragement is more helpful than trying to do it all on your own. Of course, in the end you do have to do most of it on your own.

KL: What advice did you find yourself giving students most often, and does it still hold true for you?

HR: I have taught poetry courses, but over the last twenty-five years I’ve mostly taught creative non-fiction. I often quote Lytton Strachey’s comment that ‘Discretion is not the better part of biography’ and then add: ‘Nor the better part of autobiography.’ I also suggest that mixed feelings are more interesting to write out of and about than clearcut ones. If you’re writing about someone else, pure admiration tends to produce hagiography, pure dislike a vindictive portrait – all warts, rather than warts and all. Serious doesn’t mean earnest; you can be serious and funny at the same time.

KL: What is the best advice you’ve received as a writer?

HR: The best advice it would have been helpful to be given (but no one did) would have been: ‘Don’t eat your heart out trying to be a kind of writer you aren’t (say, a novelist). Try to find out what kind of writer you are and pursue that as hard as you can.’ Chaucer knew: ‘The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne.’

KL: Which authors do you most often recommend to students or emerging poets?

HR: I mostly suggest they should read as widely as they can and that they should read as a writer.

KL: What writers are you returning to most these days?

HR: I often go back to Montaigne’s essays and Orwell’s and Virginia Woolf’s. Poets I often reread include: Derek Mahon, Hugo Williams, Thomas Gray, Wendy Cope, Fleur Adcock, Edward Thomas, Andrew Marvell, Seamus Heaney, Lauris Edmond, Anne French, Robert Browning, Thomas Hardy, Philip Larkin …

KL: What responsibilities do reviewers have to writers, and what responsibilities do they have to readers?

HR: Reviewers have an obligation to be fair-minded towards their subject and to write something as worth reading (ie well-written and enjoyable) as any other piece of prose.

KL: How can reviewers give criticism that is honest yet constructive?

HR: They should try to understand what the writer was aiming at (rather than the thing they think the writer should have been aiming at) and judge the work accordingly. This is easier said than done. Writers rarely remember the positives reviewers say, and rarely forget the negatives. Reviewing is hard, if you’re trying to do a good job. In a small country like New Zealand, there’s only one-and-a-half degrees of separation, which makes puffing and pulling your punches a tempting prospect.

KL: What kind of legacy do you hope to leave through your poetry and teaching?

HR: Whatever legacy you might leave (and few writers or teachers in the scale of things leave any) is not up to you. But of course writers hope people will positively remember something they’ve written and that their work will continue to be read after their death. When I think of the teachers who have matter to me, I think of them with immense gratitude and I hope some of my pupils might feel something of that, too.

KL: Is there a question about your work that you wish people asked more often?

HR: Interesting question, but I don’t really have an answer. Perhaps ‘Why, given that you also write plenty of poems in free verse, do you still think that there are possibilities in fixed poetic forms like the sonnet, villanelle and triolet?’ I could talk about that for a long time.

KL: If your life was a movie, what would the audience be screaming out to you now?

HR: Keep going! Well, I’d like to think they might.

KL: What’s next for you? What are you working on now?

HR: I’m threequarters of the way through a second volume of memoirs and about to write about a particularly difficult part of my life. I want to finish that and then a third volume, if I can. And write more poems.

*This interview has been conducted through emails.

Click here to read Harry Rickett’s poem.

.

Keith Lyons (keithlyons.net) is an award-winning writer and creative writing mentor originally from New Zealand who has spent a quarter of his existence living and working in Asia including southwest China, Myanmar and Bali. His Venn diagram of happiness features the aroma of freshly-roasted coffee, the negative ions of the natural world including moving water, and connecting with others in meaningful ways. A Contributing Editor on Borderless journal’sEditorial Board, his work has appeared in Borderless since its early days, and his writing featured in the anthology Monalisa No Longer Smiles.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International