The story of Hawakal and a conversation with the founder, Bitan Chakraborty, whose responses have been translated from Bengali by Kiriti Sengupta.

Hawakal Publishers grew out of the compulsive need young Bitan Chakraborty had to express and connect. This was a young man who was willing to labour at pasting film hoardings to fund his dreams. An Information Technology professional by training, Chakraborty realised early he did not want to tread on trodden paths and started his journey as a creative individual. Now, he not only writes and publishes but also designs the most fabulous covers and supports local craftsmen.

Over the last nearly two decades, the brand Hawakal has become synonymous with traditional poetry publication from India. They do not offer buy back deals or ask to be paid like most publishers but pick selectively. No one seems to know what it is they look for. All Chakraborty says is – “We aimed to introduce a fresh wave in publishing.”

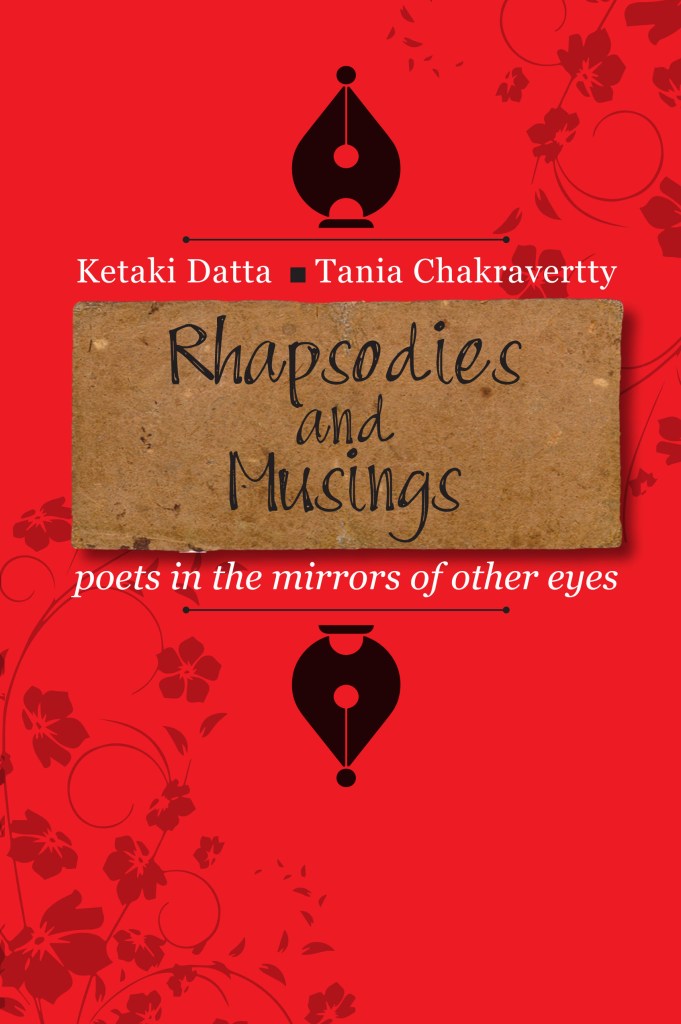

Chakraborty writes fully in Bengali which is why the dentist-turned-writer-turned-publisher, Kiriti Sengupta, had to chip in with the translation of his responses in Bengali. Their friendship matured over the last decade when Sengupta approached Chakraborty to publish a book of critical essays, which along with essays on Sharmila Ray’s poetry homed critical writing on his too. This was the first English publication of Hawakal.

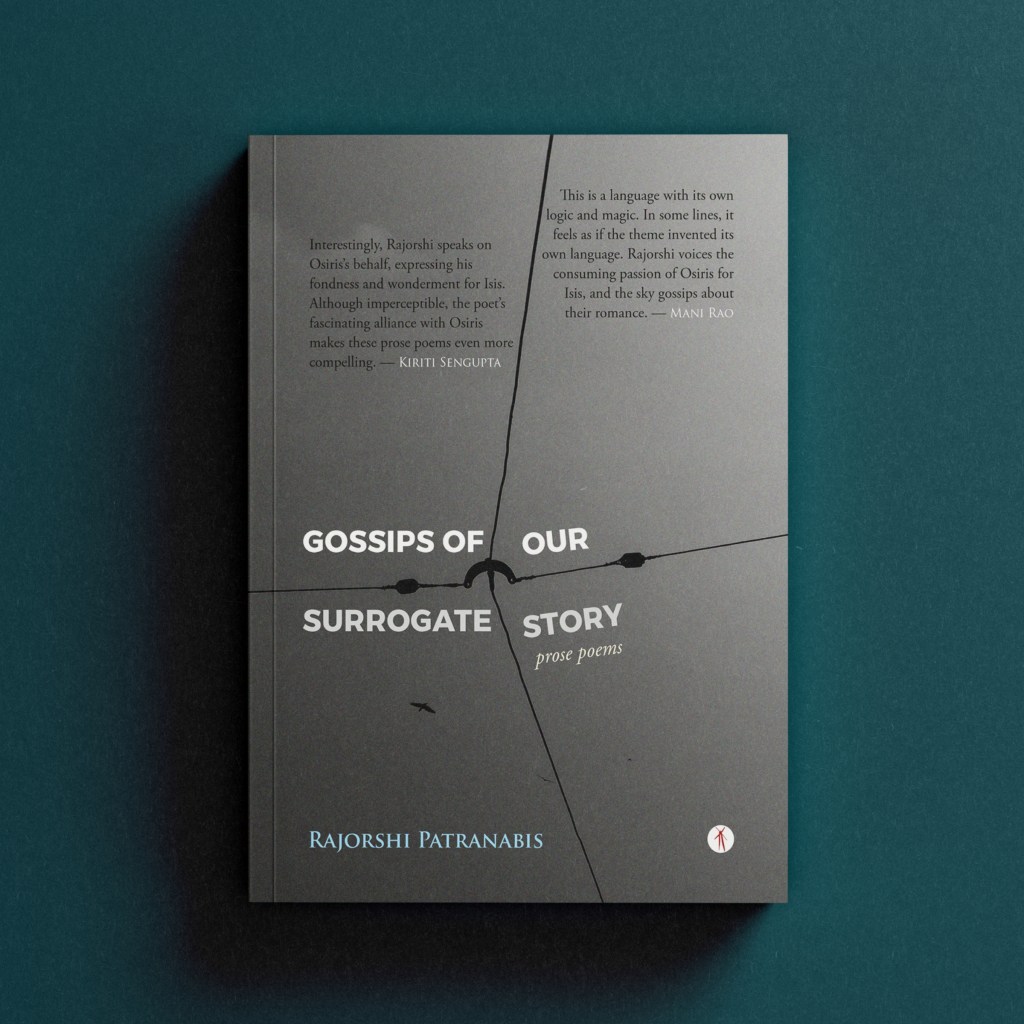

Sengupta had given up dentistry by then and was living in a hostel on a packet of Maggi a day to indulge his creative passions. A skilled poet with a number of books under his belt, he eventually joined Chakraborty to run the English section of Hawakal. He also translates from Bengali to English. We have one of his translations of Chakraborty’s short story, Disappearance. A powerful reminder of social gaps that exist in the Subcontinent, it’s a poignant and frightening narrative, the kind someone writes and imagines out of a passion to reform.

Some of Bitan’s works are available in English. His style — by the translations — seems graphic. The deft strokes make the landscape and the stories almost visual, like films.

Chakraborty worked with ‘Little Magazines’ for some time. Then he made his way into publishing full time. Though he found it hard to make ends meet, he started his adventure without compromising his beliefs. He wanted to take books to readers and, with that spirit, they started the Ethos Literary Festival, where they host writers published by them. In fact, in the 2025 festival, Hawakal sold more than 400 books in seven hours! Who said poetry doesn’t sell?

Chakraborty and Sengupta have yet another hallmark. They wear matching clothes. These are tailored with material sourced from handloom weavers. They resorted to this when they found that commercialisation was killing the traditional homeborn handlooms. In that spirit, they started a clothes venture too, Mrinalika Weaves.

Chakraborty is an unusual person – as the interview will reveal – humble, stubborn with aims like no other publisher or writer in this day and age! He doesn’t talk of money, survival, politics, awards or glamour, but what matters to him. He is direct and straightforward and perhaps, his directness is what makes his outlook appealing. He translates a few to Bengali for his own growth. But these are poets who are known for their terse writing. Maybe, that is what he looks for… Let’s find out!

Conversation

Bitan, you are a multifaceted person: a writer, an artist, a photographer, and, most importantly, a publisher for all writers. What is it you most love to do and why?

I need to talk. What I observe or learn from my experiences compels me to express myself. Therefore, regardless of the medium I use, I strive to convey meaningful messages. Nevertheless, the range I enjoy in weaving words is unparalleled.

What sparked your interest in writing? Please elaborate. Do you only use Bengali to communicate with others? Do you translate from other languages to Bengali?

I felt emotionally down when I began writing. What a dreadful time it was! I believe it must be the emotional turmoil of my youth. However, writing has never left me since then. It’s more accurate to say that I have never managed to rid myself of my urge to write. During the early period, my writings contained more emotion than substance. In my college years, I was engaged in student movements that helped me discover the purpose of words. Society, socio-economic status, politics, and human dissatisfaction are the themes that run through my stories. Bengali is my mother tongue: I think, speak, dream, and curse in Bengali. I find it challenging to derive the same pleasure from using another language; it is my shortcoming.

Nevertheless, when I meet outstanding works in English, I attempt to translate them into Bengali. Not everything I read, but I have translated poems by Sanjeev Sethi and Kiriti Sengupta. I have consistently translated Gulzar into Bengali, but it has yet to be published in book format. Translation is a mental exercise; it particularly helps when I am experiencing writer’s block. I read poetry when I wish to untangle my thoughts, and when I come across fine poems in another language, I try to make them my own — bring them into my culture through translation.

Do you write only prose or poetry too?

I have been writing stories and essays for the past fifteen years. Interestingly, I began with poems, but they turned out to be junk. Therefore, I focussed on writing fiction.

Many of your stories focus on the Bengali middle class. What inspires your muse the most? People, art, nature, or is it something else?

I grew up in a lower-middle-class environment. Poverty, unemployment, and debt were parts of my formative years. I witnessed how this economic disparity allowed a particular segment of society to insult and humiliate others. Consequently, I have developed a strong affinity for those who are underprivileged. Later, when I began writing fiction, my political awareness enhanced my observations — I was able to merge the existing economic inequality with the nation’s political perspectives. The lessons I have learned over the years motivate me to write.

You design fabulous book covers. Do you have any formal training, or is it a natural flair?

When I entered the publishing industry, I had no funds to commission professionals for book covers or layouts. I had been involved with Little Magazines since my college days. I used to spend hours with the printers, meticulously observing how they designed cover spreads and interior text files. This experience proved useful when I began producing books. For the past several years, I have frequented bookstores, picking up a book or two — I also purchase books online, especially those that help me stay abreast of recent developments in book architecture. In my early years, I was unable to learn design formally due to financial constraints.

When and why did you decide to go into publishing? Could you tell us the story of Hawakal?

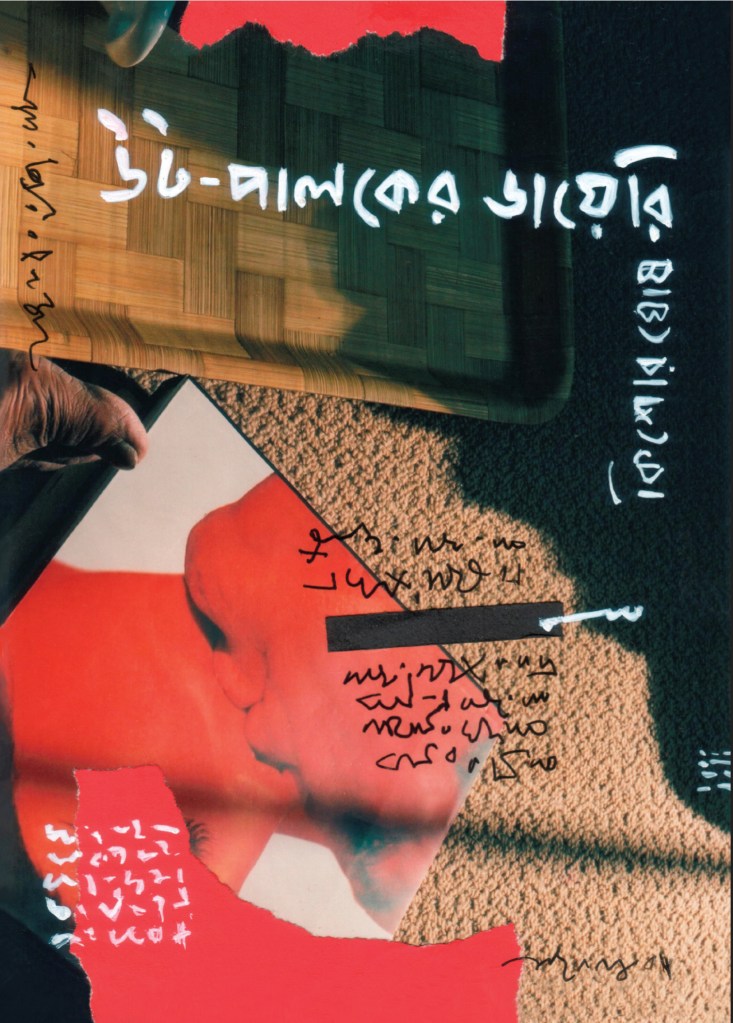

From 2003 to 2008, I was involved with four Little Magazines. Bengali Little Magazines thrive on minimal funds. Therefore, we (the team) managed everything necessary to publish a little magazine. We oversaw printing, distribution, book fairs, and other activities. By the middle of 2007, I realised I wasn’t suited for a day job. I understood that I would struggle to survive the conventional 10 am to 5 pm career. During that time, my family was in financial difficulties. Suddenly, we had the opportunity to publish Kishore Ghosh’s debut collection of poems, Ut Palaker Diary. It was published under the banner of the little magazine I was actively working with. As we worked on the book, I learned that publishing a magazine and publishing a book were entirely different endeavours. A little magazine is primarily sold through the efforts of its contributing writers and poets, while a book is sold through the combined efforts of the author and the publisher. I decided to pursue publishing as my career after we successfully sold 300 copies of Ghosh’s book in 10 months. That was the beginning.

Why did you opt to name your firm after a windmill — Hawakal in Bengali? Please elaborate.

We spent days selecting a name for our publishing concern. Finally, we chose the title of one of Kishore Ghosh’s poems as our company name. Hawakal, in English, means windmill. It signifies an alternative source of energy. We aimed to introduce a fresh wave in publishing. As an independent press, we have consistently operated ahead of our time. From developing a fully-fledged e-commerce hub (hawakal.com) in 2016 to producing the highest number of books during the pandemic (2020-2021), Hawakal has accomplished it all.

You have boutique bookshops in Kolkata, Delhi — any other places? I believe you started a collaboration to get your books into the USA? Could you tell us a bit about your outlets and how you connect writers with the people? Are your boutique shops different from other bookshops? Do they only stock Hawakal books?

As you know, Hawakal has two functional ateliers in Delhi and Kolkata, while our registered office is located in New Delhi. We do not have any plans for an additional studio in India. We also have a bookstore in Gurgaon called Bookalign. There is a small outlet in Nokomis, Florida. It is a new unit in the United States. We primarily stock books published by Hawakal and its imprints (Shambhabi, CLASSIX, Vinyasa). However, we carefully select titles from other publishers for our store. We have sufficient seating in the store, allowing readers to browse the books before making a purchase. Since we publish non-mainstream authors, readers need to make a conscious choice. This not only benefits the authors we publish, but it also helps us evaluate the effectiveness of our selection process.

You started as a Bengali publisher, if I am not mistaken, and then forayed into English; now you are bringing out a translation in Hindi? How many languages do you cover? Do you plan to go into publishing in other languages?

We initially focused on Bengali books. Our venture into English titles began when Kiriti Sengupta joined Hawakal as its Director. Publishing a Hindi book was unexpected. However, we will not release books in other languages that we cannot read or speak. It is essential, as a publisher, to be well-versed in the language of the books we publish.

What kind of writers do you look for in Hawakal?

Would you like me to reveal the truth? We expect more than just satisfactory work from our writers: we want writers who will value their work passionately and take the necessary steps to reach a wider readership. Please don’t assume that what we expect from our authors is not something we adhere to ourselves. We expect this because we understand what it means to be truly passionate about one’s writing.

I heard that Hawakal was diversifying into textiles. How does that align with your writerly and publishing journey?

We opened our first kiosk in Mathabhanga, North Bengal, back in 2016. We simultaneously sold books and sarees from that small outlet. We had to close the shop due to a lack of staff. Kiriti Sengupta has long cherished the dream of representing the fine textiles of Bengal. Our family has grown larger. Bhaswati Sengupta and Lima Nayak have joined the team; they are the ones who established Mrinalika, collaborating with artisans from remote regions of India to showcase their creations to a wider audience.

Where do you envision yourself and Hawakal, your most extraordinary creation, ten years from now?

We aim to publish fifty timeless books over the next decade.

Thanks for your time and for the service you render to readers and writers.

[1] Ut Palaker Diary – Diary of a Camel Herder

Click here to read Disappearance, a story by Bitan translated from Bengali by Kiriti Sengupta.

(This feature — based on a face to face conversation — and online interview is by Mitali Chakravarty)

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International