Book Review by Rakhi Dalal

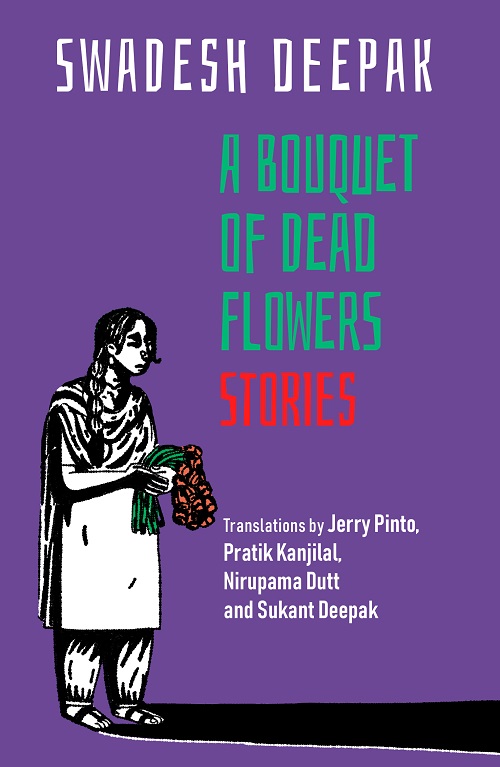

Book Title: A Bouquet of Dead Flowers

Author: Swadesh Deepak

Translators: Jerry Pinto, Pratik Kanjilal, Nirupama Dutt, Sukant Deepak

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

“Hindi literature, Swadesh Deepak maintained, had to be forced out of its comfort zone. The reader here is treated no less savagely,” writes Jerry Pinto in his introduction to this collection of ten stories by Swadesh Deepak, an author and playwright who was born in Rawalpindi on 6th August, 1942. After his masters in English Literature, he taught for a long time at the Gandhi Memorial National College, Ambala Cantonment. Following a period of illness from 1991 to 1997, when he had little contact with anyone other than his family and close friends, he made a momentous return to the world of letters with an autobiographical account of his illness, Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha[1], and the play Sabse Udaas Kavita[2]. He received the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 2004. He has a total of 15 published books to his name including short-story collections such as Tamasha, Baal Bhagwan[3]and Kisi Ek Pedh Ka Naam Lo[4]and hugely successful plays such as Court Martial and Kaal Kothri[5]. In 2006 he left home for a walk and never returned. He has been missing ever since.

These stories, deeply unsettling, challenge readers by taking them into a world where unknown forces work mysteriously, upending and affecting the lives of its characters, leaving them vulnerable at the mercy of chance happenings which rarely bring them relief. Much akin to what Thomas Hardy called as the Immanent Will — a blind and indifferent force determining the fates (and generally blighting the lives) of the privileged and the common people alike.

Whether it is the hunger for food, a ravenous longing of the starved and the deprived as portrayed in the stories ‘Hunger’ and ‘The Child God’, the mystery around the fate of a loved one in ‘For the Wind Cannot Read’, the struggle with depression in ‘Pears from Rawalpindi’ or ‘Horsemen’[, the unrequited yearning for a life of togetherness in ‘Dread and Dead End’, the author’s masterful play of the elements comes to the fore with an intensity that shakes and stuns the reader. Pinto refers to the author as the master of neo gothic,

The sunlight, the wind, the trees, the figure of a broken man, appears again and again. It seems as if it is just not the fate but also the forces of natural elements that keep rattling the course of the lives of the characters. The trees stand as guards, or sway in delight or offer a refuge, the sunlight “makes a hesitant arrival” sitting quietly or climbing the hills or sometimes streaking in the rooms, the wind is at times playful and at others vindictive. Then there are the flowers, the dead flowers of memories, whose bouquets one keeps holding, clinging to and clasping. And then there is the poetic play of words – “a pale yellow georgette afternoon in November” – bringing to life the patchy sunlight of autumn.

In the figure of broken man which appears again and again in stories, the author seems to be questioning the role that society has forced upon a man – that of a provider of the family, a role sometimes begrudgingly assumed in the stories because “no one respects a man without work, no matter how talented he is.”

In each story, the author weaves a tale that becomes a commentary — on society and its inherent evils, on relationships within a family stifled by arrogance, ignorance or circumstances and quietly working on the minds of those inhabiting it, on human greed engendered by depravity, hunger or lust, on the mysteriousness of fate whose force makes the mighty cower.

The translation, well executed, offers a closer reading experience and leaves a bilingual reader with the wish to approach the author’s works in original as well. I must make a special note on the introduction by the acclaimed writer and translator Jerry Pinto who offers a peek into the mind of Swadesh Deepak through a couple of excerpts of the author’s conversations with his psychiatrist and also with a convict brought to the hospital for evaluation. Perhaps these ideas had haunted him in the mental ward of the hospital and later seeped into his stories. Pinto in the introduction not only seeks to make sense of Deepak’s writing but also makes for a compelling reason to read his works – to read on without looking over one’s shoulders.

.

[1] I have not seen Mandu

[2] The Saddest Poem ever Written

[3] The Child God

[4] Name a Tree, any Tree

[5] Dark Chamber

Rakhi Dalal is an educator by profession. When not working, she can usually be found reading books or writing about reading them. She writes at https://rakhidalal.blogspot.com/ .

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International