By Tamara Raza

Tuberose, a perennial species of the asparagus family and a native of Mexico has somehow found a home in India too. It blooms at night, which makes sense as in Hindi, it’s a compound of two words – ‘Rajni’ means night, and ‘gandh’ is the smell. It exudes the intense smell of the night, and the long, slender stems supporting the white waxy flowers at the top reinforces its nocturnal beauty. In the world of perfumery, tuberose is a prime source of scent production.

shaam kī ḳhāmosh rah par

vo koī asrār pahne chal rahī hai

rajnī-gandhā kī mahak bikhrī huī hai

duur peḌoñ meñ chhupī dargāh tak

(In the silence of the evening

She is wearing a mystery

The aroma of rajnigandha is scattered

As far as the hidden shrine among the distant trees)

-- Dhoop Ka Libaas (The Robes of the Sun) by Yameen( 1286-1368)

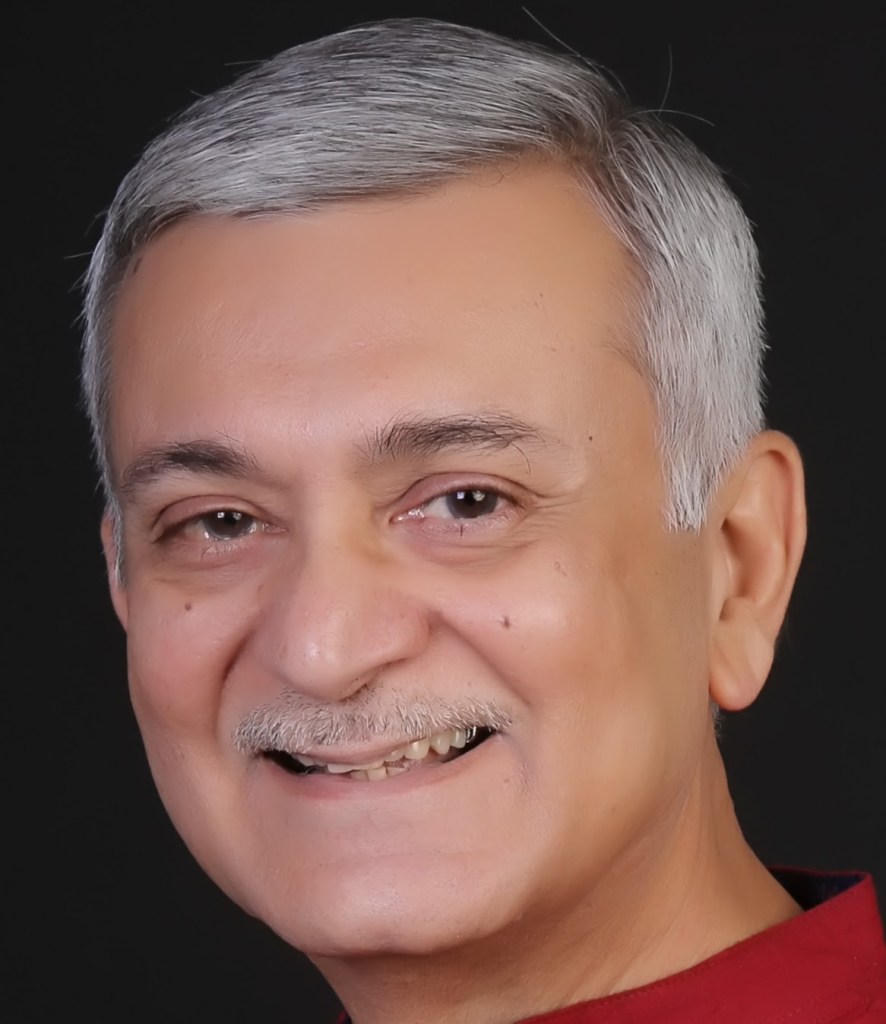

Like the aforementioned nazm, the perfume of tuberoses seem emanate from Basu Chatterji[2]’s 1974 film Rajnigandha too, a movie based on Mannu Bhandari’s story Yahi Sach Hai (This is the Truth). Deepa, played by Vidya Sinha, is the protagonist of the film who struts across the road, waits at a bus stop, with her saree pallu[3] resting on her right shoulder, and is annoyed at Sanjay’s constant tardiness. Sanjay, portrayed by Amol Palekar, is a freewheeling man with a chronic urge to converse excessively and forgets almost everything he was supposed to do. But when she looks at the bunch of Rajnigandha he brings for her, she forgets all her qualms about him. Rajnigandha phool tumhare yunhi mahke jeevan mein (May the fragrance of your tuberose keep blossoming in life), the verse from the film’s song, likewise, is Deepa’s prayer for life.

Deepa, a headstrong woman living in the Delhi of the 1970s, is in the final stages of writing her PhD thesis and is on a job hunt. Sanjay, on the other hand is a more laid back fellow with “just a BA” working in a firm, and fortunately does not suffer from a fragile male ego which feels threatened by a more qualified female partner. A job interview entails Deepa traveling to Mumbai where she meets her former flame, Navin (played by Dinesh Thakur). Seeing him again rekindles her feelings for him. Navin is a go-getter living the fast life of Mumbai, whose advertising job made his way into the party life of the city. Navin’s personality symbolises thrill and adventure, whereas Sanjay on the other hand perhaps defines stability, if not standstill, in life. Deepa is thrown into the dilemma of who should she choose, Navin or Sanjay, much like the film’s song, Kai Baar Yunhi Dekha Hai (Often, I have Seen), which essentially is the musical expression of Deepa’s situation, that says “Kisko Preet Banau? Kiski Preet Bhulau?” (‘whose love shall I accept, whose love shall I forget?’). While Navin does notice Deepa’s appearance, manages to be on time, he is also the one who broke her heart in college. Sanjay, on the other hand, who is hardly on time, forgets the film tickets he was supposed to bring, fails to notice what saree Deepa was wearing, and annoys her to the core, would probably never go as far as breaking her heart.

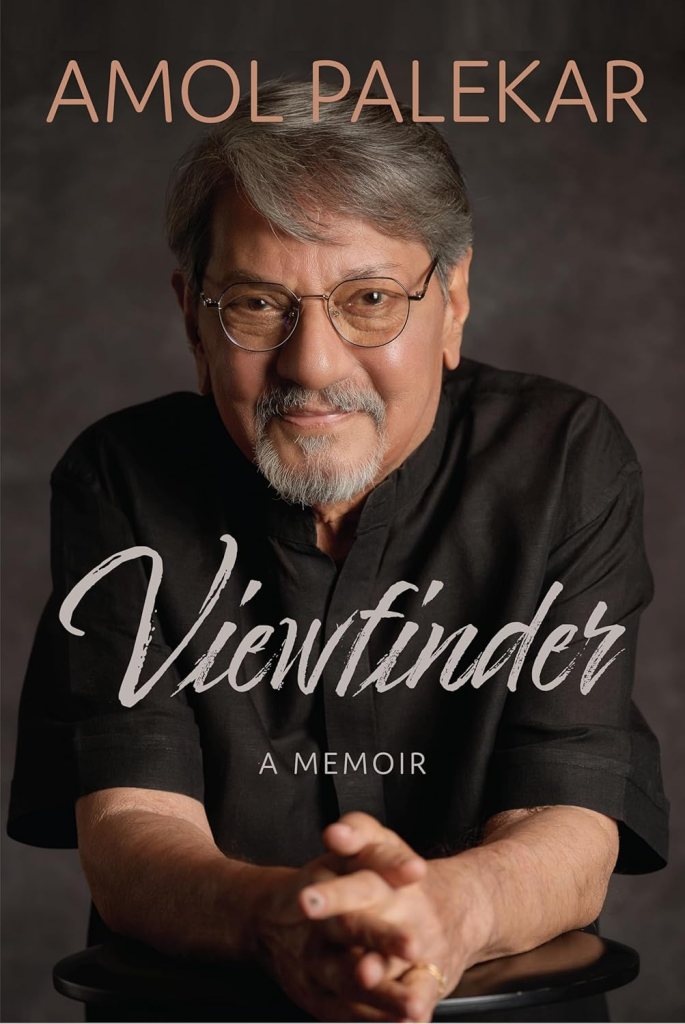

“Crafting Sanjay—a loquacious character who never explicitly expresses love but conveys it through his eyes—without making him seem selfish, was a challenge,” writes Amol Palekar in his memoir, Viewfinder. Both men however, had one similarity – the zeal for protesting, for unionising against injustice in their respective positions, a virtue that presumably was not surprising for the people belonging to the first generation of young independent Indians. The Deepa that Mannu Bhandari writes about appears firmer and bolder in her stances than the one Basu Chatterji crafted on screen, who is more shy, more reticent and even more confused.

While India did get its first and only woman Prime Minister by the 1970s, in Bollywood, it was the era of the ‘Angry Young Men’ that defined the careers of actors like Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan, and Rajesh Khanna, who embodied the larger-than-life character of the ‘hero’ in Hindi cinema and received a cult following as well. On a parallel but divergent plane, there emerged a different kind of male protagonist: he was the guy next door, a middle-class, urban, white collar office goer, who travelled in public transport and spoke no flashy dialogues. A point to be noted here is, that the said definition of the character also included that they were primarily English-educated and from a comparatively well-off background — compounding to the ‘middle-class’ phenomenon in urban India. This was the characterisation that Amol Palekar adopted with films like Rajnigandha, Chhoti Si Baat (A small Matter, 1975) and Baaton Baaton Mein (Between Conversations, 1979). Basu Chatterji’s films underscored this portrayal of the ordinary, urban middle class milieu which was often absent from the mainstream commercial Bollywood films from that time.

With no surprises, the men in these films, like Sanjay in Rajnigandha, are not perfect feminist characters. From a snapshot in the film, Sanjay tells Deepa to keep her money to herself after marriage because the household shall be run with “his” money. Ideally, in an equal household, if both partners have a source of income, the expenses should be shared by both of them, which defines the ‘partnership’ in a relationship in the most literal sense of the term. Considering the time and space of when the film was made, it appears that while Chatterji, consciously or not, did try to incorporate modern ideas of women’s financial independence, he also at the same time, could not completely erase how a conventional ‘man’ from a patriarchal ethos would react — by still upholding the status quo of hierarchy between the two sexes.

Despite these few shortcomings in the film, Deepa’s character contains a multitude of complexities, unlike many films of the seventies where female characters are often reduced to archetypes as that of the demure, submissive wife, the sacrificing mother or the unattainable love interest. She is not an overtly assertive individual but is also neither a passive receiver of love nor a woman who blindly conforms to patriarchal conventions; rather, she is someone who constantly engages with her emotions, doubts, and desires. Her emotional conflict—to choose between thrill and stability, novelty and convention—reflects the larger question of female autonomy in a culture where women were often expected to follow predetermined roles. Although Deepa’s predicament is not a radical departure from typical romance plots, her internal journey is far more introspective and self-aware than the majority of female characters in the films belonging to that era. She is not a mere object of male desire or a meek heroine waiting to be ‘saved’ by a male hero. She is an individual in her own right, capable of making difficult choices that reflect the evolving understanding of herself.

Deepa’s decision-making isn’t straightforward or even particularly idealistic, but not once does she lose her individual agency to feel for herself and the emotional depth in her character offers a fresh perspective on the representation of women in Hindi cinema, portraying them as individuals with competing needs and aspirations, rather than as mere props for male narratives. Maeve Wiley, the protagonist from the Netflix show, Sex Education, calls “complex female characters” her “thing.” Well, this author’s proposition would be to include Rajnigandha’s Deepa as well into this list.

In its subtle critique of the pressure on women to conform to the traditional idea of womanhood, this film however does not provide any revolutionary discourse to the existing social and cultural norms surrounding women’s roles. It still runs on the same old conventional path that expects a woman’s happiness and worth to be defined by her relationship with a man. But it nevertheless has been able to depict a self-reliant woman whose existence itself is an act of revolution in male dominating spaces such as that of earning a doctorate in the 1970s.

Basu Chatterji, known for his ‘middle-of-the-road’ cinema was part of the Film Society Movement. According to historian Rochona Majumdar, the Film Society activists grappled with the definition of a “good” film. Was it’s primary goal to improve the lives of the Indian people, a goal that mainstream (profit-driven) “commercial” cinema had failed to accomplish? Or was it just to “mirror the aspirations of common people” through cinema, as one early film society activist put it? In line with the same thought, this film with no dramatic plot twist or a visible antagonist per se, stands out as a celebration of the ordinary, an ordinary man, an ordinary woman, travelling in public transport, with ordinary aspirations. Not to mention, this ‘ordinariness’ had a certain class and religious position as well.

The tuberoses could also perhaps be taken as an allegory of the ordinary. While conventionally, a rose is sought to be the flower connoted with love and romance, with countless romantic poems mentioning it, the tuberose in comparison appears to mundane. When one buys a bouquet, two-three tuberose stems are often seen given the geographical and seasonal context, but just as a supplement to the more prominent flowers wrapped in it. So, does this flower in the film symbolise a sense of yearning or through it, is it an attempt to tell an ‘ordinary’ love story?

The film’s title Rajnigandha does not just symbolise love or longing but aptly reflects the emotional tone of the film. Just as the flower blooms at night, Deepa’s journey towards self-realisation and emotional clarity unfolds in the quiet, introspective passages in the story, rather than in conspicuous expressions of passion or drama. Her feelings and relations are complex, layered, and occasionally challenging to describe, much like the flower’s euphoric yet elusive nature.

It won the Filmfare Critics Award for Best Movie, with two songs penned by the Hindi lyricist Yogesh, bagging Mukesh[4] the National Award for Best Male Playback Singer, and no distributor willing to buy the film initially, Rajnigandha also passes the Bechdel Test which examines how women are represented in films with distinction. This to me is its greatest triumph. Its delicate yet profound meditation on love, choices, and identity, is a masterwork of Indian cinema that contemplates on the silent, unpronounced qualms of daily life by fusing realism with emotional profundity. An honest depiction of human emotions, tastefully rendered in a small, intimate canvas, is what all works of Basu Chatterji (not just the film in question) deliver as a welcome diversion in an age of exaggerated melodrama and action. And Rajnigandha is a film that reminds people to value the nuances of human relationships and the elegance of slow, quiet cinema, making it a timeless classic.

[1] Perfume

[2] Basu Chatterjee, film director and screen writer (1927-2020)

[3] Loose end of a saree

[4] Mukesh Chand Mathur (1923-1976), playback singer in films

Bibliography:

- MAJUMDAR, ROCHONA. “Debating Radical Cinema: A History of the Film Society Movement in India.” Modern Asian Studies 46, no. 3 (2012): 731–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41478328.

- Read full Nazm by Yameen, Rekhta.

- Sansad TV, Guftagoo with Amol Palekar, YouTube, 2015, October 21.

Tamara Raza is an undergraduate student at Indraprastha College for Women, University of Delhi.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International