Ratnottma Sengupta revisits an exhibition full 25 years later

On November 1 of 1956 was born a state in Central India called Madhya Pradesh. And 44 years later, on exactly the same day of November 1, in the year 2000 it was remapped. A new state — Chhattisgarh — was carved out of the land that had been home to the oldest Indians: the men and women who had peopled the caves at Bagh and Bhimbetka.

Standing at the threshold of that new beginning, I had curated an exhibition titled Anadi – that which has no beginning and, therefore, no end. The exhibition card was designed by M F Husain who came on the inaugural day in Delhi. The next day was graced by the presence of Madhavrao Scindia, scion of the royal family that continues to throw up political leaders. I was fortunate to have friends like collectors Anand Agarwal and H K Kejriwal, bureaucrats Bhaskar Ghose and Sarayu Doshi, art lovers like poet Gulzar and artists like Yusuf Arakkal. Happily, then, the exhibition travelled to Birla Academy in Kolkata to Chitrakala Parishath in Bangalore to the National Gallery of Modern Art in Mumbai. And with it travelled a batch of youngsters who were soon to be among the most sought after names in Indian Contemporary Art.

What made that exhibition so special? The card? The multi-venue display? The star viewers? The exhilarating combination of tribal paintings, figurative sculpture, and abstract images? Twenty five years later, I will look back to find an answer.

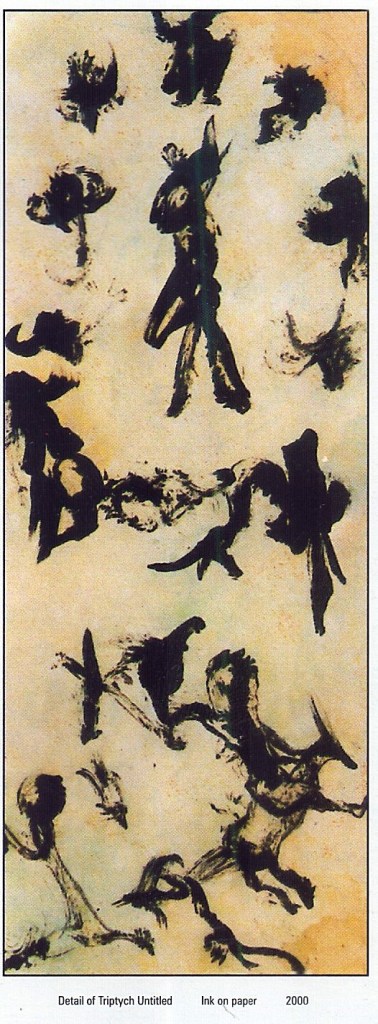

At the intersection of two millennia I was amazed to note there was no rupture in continuity. Anadi offered a fresh look at a continuum that lives on beyond the geopolitical redefinition, because it began at a time when Chhattisgarh was not Madhya Pradesh, nor the Central Province of the Raj. Bhopal, Indore, Raipur, Jagdalpur, Sanchi, Vidisha, Malwa… these cities had no chief minister back then, nor a Prime Minister. Why, there were no Begums nor a Buddha. No Baj Bahadur loved a Roopmati nor did Kalidasa send a Cloud as Messenger. It was a time when the intrepid fingers that harnessed stones and hunted hides also painted rocks to sing of life. In the process – around 10,000 BCE – they crafted the rockbed of Indian Art at Bhimbetka, the UNESCO World Heritage Site mere miles away from Bhopal.

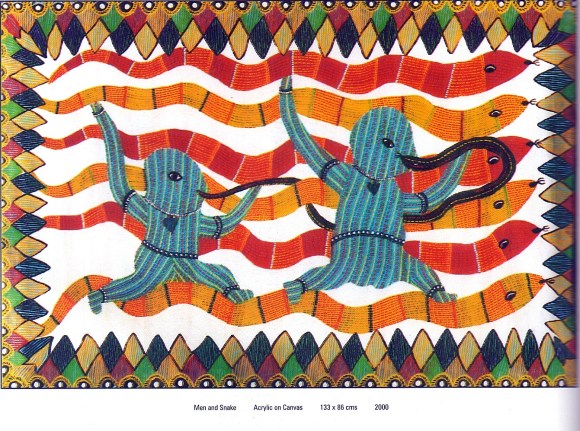

Bare lines that captured with only a twist and a turn the vigor of hunting and the verve of dancing, rock art is that elusive genre which is narrative, figurative and abstract – all at one go. And that is a characteristic common to the tribal stream of art which flourishes in the state from a forgotten past. There is a story in every figure painted by Bhuri Bai or Sukho Korwa. She paints a cart and tells you of the festival day when on its wheels it goes round habitats, collecting all the bimari and driving illness out of the village. He paints a bird that pounces on a snake which devours a rat, recounting the lifecycle that sustains ecological balance. But where is the third dimension? Where’s the likeness to the world of five senses? We see no effort here to evoke either. Instead, there is a stylization which is unique to the region that is home to the Bhil, Gond, Sahariya, Baiga, Saur and other tribes. A stylisation that abstracts the essence of the physical reality they celebrate through colour and line.

Dots and crosses, circles and squares all come into play as the vivacious blues and reds, yellows and greens acquire life. A line is not simply a straight line or curve: that would be an unappetising repetition. The quest for variety and individuality finds Kala Bai, Lado, Sumaru break up the lines into an intricate arrangement of countless motifs. When the subject is the same, as too the colour, it’s the dots and crosses, dashes and stars that give the work the imprint of individuality. In the process, these artists who work in a community and send off their creations to markets in distant cities, have worked out a way of ‘patenting’ artistic property. Tradition did not require them to ever sign off a work with their names. In the age of copyright awareness and intellectual property rights, they might put their signatures on the canvas – but the unmistakable imprint of the artists lie in the manner of their assembling the familiar patterns.

That, make no mistake, is the sign of a master, be he in the tribal mould or a modernist. For corroboration, we have only to look at a painting by Maqbool Fida Hussain, N S Bendre or Syed Haider Raza. Madhuri or Mahabharat, Gandhi or Indira, M F Husain constantly painted figures. Eminent and easily recognised ones at that. And yet, they lived not in the details of their features but in the lines and colours that spelt ‘Husain’ to seasoned viewers. Likewise Bendre’s forms had little concern for photographic realism. In Raza’s case, it is the arrangement of colourful geometrical bindus (circles) and squares alone that speaks of the artist. So, regardless of whether or not there is a ‘McBull’ or ‘Bendre’ inked on the canvas, we readily identify these masters who, incidentally, all came from this same state of Madhya Pradesh.

Note one more thing about these names. Each of them had set new watersheds for Indian contemporary art. All of them had opened up new avenues for artists who came after them. Bendre, the first to head the art education at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, gave not just one more centre for mastering the brush. He gave shape to an institution which still assimilates the best of the home and the universe, giving the MSU artists a rare acceptability in India and in the West. Raza, who lived in Paris for years and years, did not sever his umbilical cord with this soil, yet carved a niche for Indianness in the Mecca of contemporary art. And Husain? The life as too the art of this ‘Picasso from Indore’ had become a legend in his own lifetime. Who else but MF could raise the high water mark at auctions, again at again, at home and abroad? Who but him could open up the markets for Indian artists, including those who preceded him like Jamini Roy?

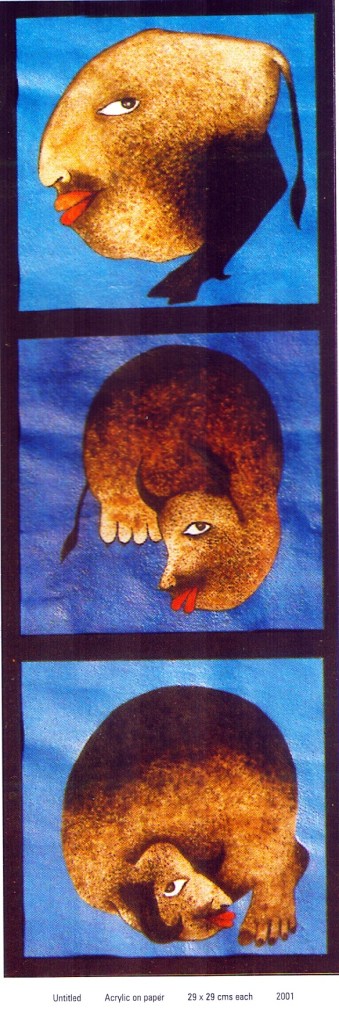

Talking of the masters who opened vistas, especially in the context of Madhya Pradesh, one comes to J Swaminanthan who facilitated a two-way transaction. While holding the reins of Roopankar Museum in Bhopal, he assimilated tribal art to such an extent that he could understand it, explain it, talk about it, write about it and paint after them, using their earth colours, and the bareness of their lines. At the same time, the outsider who became an insider gave, through Bharat Bhavan, all of Madhya Pradesh a new standing in the realm of contemporary art. Artists from all over the country would congregate in Bhopal with their art, exhibit it, discuss it threadbare in seminars, impart it to those keen to learn. Small wonder, the state boasts a host of artists like Akhilesh and Anwar, Seema Ghuraiya and Manish Pushkale, Yogendra and Vivek Tembe, Jaya Vivek and Jangarh Shyam. Artists who steal the attention of the world today.

This breed, which was born with the emergence of the state, came of age in artistic terms as the province consolidated its presence on the marquee. And an overwhelming number of them express themselves in just lines and colours. They care not for things like market – which seems to have an insatiable appetite for figurative art. Nor for the narrative tradition of the forefathers who painted on rocks. These neo-masters are all distilling forms, extracting experiences, working out their own equations with abstraction.

But, come to think of it, isn’t this exactly what the original artists of this land – and every other land on earth – set out to do when they picked up the sharpened tool that was millennia away from the paint brush?

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and writes books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International