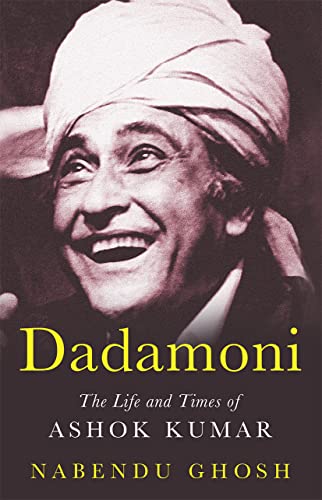

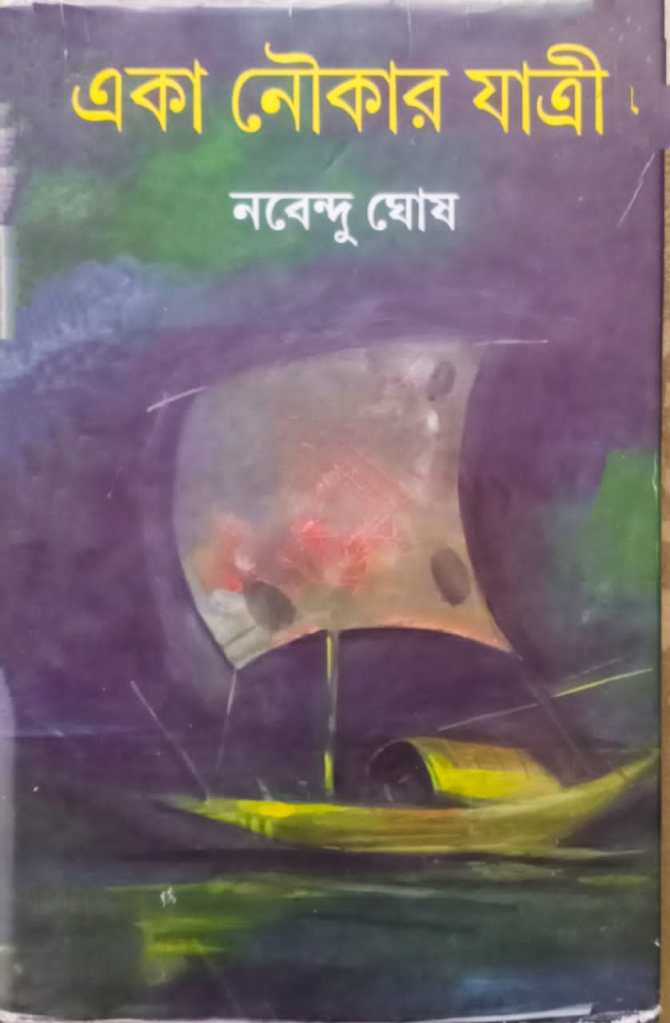

From Nabendu Ghosh’s autobiography, Eka Naukar Jatri / Journey of a Lonesome Boat, translated by Dipankar Ghosh, post scripted by Ratnottama Sengupta

By now it had become common knowledge in the Bombay film community that Bimal Roy had brought along a “writer” with his group, and apparently he was quite a decent writer. Just as, at one time, Urdu writer Sadat Hasan Manto had come to Bombay Talkies, and Urdu writer Krishan Chander too had come on the scene. There was a feeling that there might be a chance of acquiring a decent storyline from Nabendu Ghosh. Naturally, for a while quite a few producers and film directors contacted me. Story sessions were held at Van Vihar, or at the offices of the producers concerned. but there seemed to be a lack of appreciation from these people to stories that came from the mind of an alumni of the Progressive Writers Association. They were all of the opinion, “The idea is great Ghosh Babu, but it is too idealistic. Dada we want to make movies with Dev Anand and Geeta Bali, accompanied by Johnny Walker and Yakub (comedians of the time). Please tell us stories where we can incorporate them, rather than literary stories.”

Realisation soon dawned on me that the Hindi ‘filmy kahani’ was a different genre of stories. What kind of stories? In short, stories that would be appreciated by 90 percent of viewers from different states, with different tastes, all over India. Hence even a highly educated producer like S Mukherji heard the story of Baap Beti and said: “It’s a nice story but I won’t make it – I’m a businessman”! In other words the businessman had a different slant on dramatic arts: they might well say that “Bicycle Thieves is a great film but an undoable story, I’m a businessman.”

Later, on one occasion I had asked Mr Mukherjee, “You said ‘No’ to Baap Beti, yet you wanted to film the literary story, Mrit Pradip. Why was that?” Mr Mukherjee laughed. “If there is an indication of high literary merit in a story then it might well be conducive to our business, and might turn a ‘hit’ picture into a superhit.” I asked, “Does that mean a ‘hit’ is quantifiable?”

“Of course it is!” he replied. “Just as any tasty dish needs some specific spices to make it tasty.”

“But what about the healthiness of the dish? Isn’t that a consideration?”

“Nabendu Babu, I am not into the medical business.”

“Does it follow that you will cater to the mass’s addiction for entertainment without upholding the essential ideals of life?”

“I do that Nabendu Babu but in very low doses,” said S.Mukherjee. “I follow the principles of dramatic arts as laid down in Natya Shastra but I don’t profess to be a saintly sadhu. I am a very ordinary person in pursuit of happiness.”

He guffawed loudly for a bit. Then he said, “The spices I need for my ‘cinema-dish’ are these. First, the story: usually should be about love. Second: five or six memorable ‘love scenes’ or warm situations, full of fun, lovers tiffs, misunderstanding, separation and reunion. Third: obstacles to love, by a person, family or enemy. That contributes to tension or anxiety. Fourth: four to five moments of suspense: some conspiracy, someone chasing the lovers, trying to kill them. Fifth: comic moments, not mildly humorous but uproariously funny so that people roll around in bouts of laughter. Sixth: moments of tear-jerking sadness. Seventh: Fight scenes, each being individual in itself. Eighth: five to six melodious songs, of which two or three should be such that even persons with no music sense can sing them. Ninth: appropriate selection of actors and actresses. Tenth: a good director and a good music director. Finally: the right planetary configuration for audience’s applause.” Mr Mukherjee laughed out loud.

His words got entrenched in my mind. The successful ‘formula’ for a Hindi film! In other words it was the formula of a Hindi village Nautanki, no different from the Jatra formula of rural Bengal. Of a hundred films made by that formula, even if two managed to enlighten the mind or uplift the spirit, that would be an icing on the golden cake – “sone pe suhaga”. And if there was no icing, the gold that clinked in would be good enough gain, and two and a half hours will pass away in laughter and tears, in suspense and romance, with joyous humming of a few bars of melody as viewers return home to deep slumber, dreaming of the handsome features of a hero or heroine that will tickle their fancy and prove the worth of the newly invented form of art – cinema. In particular, the magic of Hindi movies.

Therefore, I decided to write or adapt stories and ideas to comply with the mandates of the Formula. Whatever good ideas came along, whether in five pages or five hundred, I would fit into two and a half hours, either by extending or shortening in a fast flowing format that would leave the viewer wondering what’s next at every turn. In other words, I would write screenplays of a different kind.

And since I was unable to uphold the higher ideals of literature on the silver screen, I would compensate for it by writing for literature. I would thereby absolve myself of my sense of guilt.

Ratnottama Sengupta’s post-script:

In 1952, when Nabendu Ghosh was narrating his story, Baap Beti, Sashadhar Mukherjee (1909-1990) was a highly successful producer who had set up Filmistan Studios in 1943 along with his brother-in-law, the legendary actor Ashok Kumar; Rai Bahadur Chunilal, father of music director Madan Mohan; and Gyan Mukherjee, director of the superhit Kismet. These personalities had broken away from Bombay Talkies after the death of its founder, Himanshu Rai.

Later in the 1950s, S Mukherjee independently started Filmalaya, noted for films like Dil Deke Dekho (1959), Love in Simla (1960), Ek Musafir Ek Hasina (1962) and Leader (1964). He is also recognised as the patriarch of the distinguished Mukherjee clan of Bollywood that boasts actors like Joy Mukherjee, Deb Mukherjee, Tanuja, Kajol, and Rani Mukherjee.

And Baap Beti? It got made into a film produced by another highly successful producer of the times, S H Munshi. Directed by celluloid master Bimal Roy, it had brought a host of child artistes who went on to become big names of the Hindi screen: Tabassum (1944-2022), who passed away in November; Asha Parekh (2 October 1942), who was bestowed with the Dadasaheb Phalke Award last year, and Naaz (1944-1995), besides Ranjan (1918-1983), the swashbuckling actor from the South.

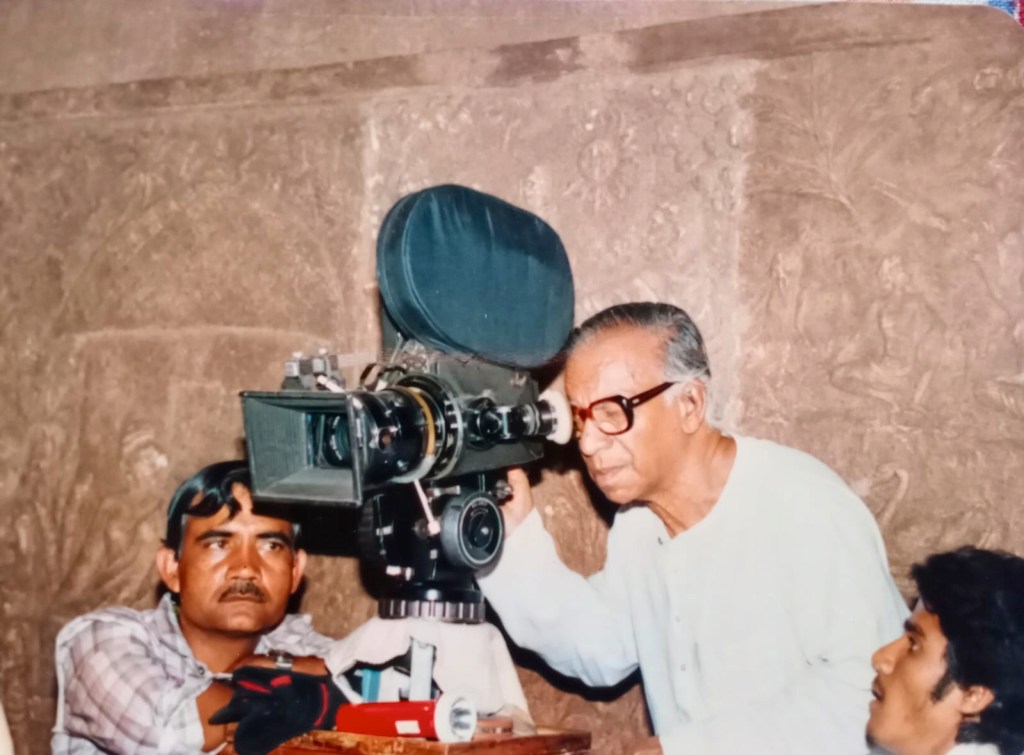

As he writes in his autobiography, after this conversation Nabendu Ghosh took a conscious decision to write his own realisations as literature, and to adapt stories by other writers for the screen. That is why we find that less than 10 per cent of the films he scripted are from his own stories. But some major directors did draw upon his stories – as Bimal Roy did for Baap Beti; Gyan Mukherjee for Shatranj (1956), Satyen Bose for Jyot Jale (1973), Mohan Sehgal for Raja Jani (1972) and Ajoy Kar for Kayahiner Kahini (1973). Only one classic that used his story but did not credit it to Nabendu Ghosh was Guru Dutt’s Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959).

Nabendu Ghosh’s (1917-2007) oeuvre of work includes thirty novels and fifteen collections of short stories. He was a renowned scriptwriter and director. He penned cinematic classics such as Devdas, Bandini, Sujata, Parineeta, Majhli Didi and Abhimaan. And, as part of a team of iconic film directors and actors, he was instrumental in shaping an entire age of Indian cinema. He was the recipient of numerous literary and film awards, including the Bankim Puraskar, the Bibhuti Bhushan Sahitya Arghya, the Filmfare Best Screenplay Award and the National Film Award for Best First Film of a Director.

Dipankar Ghosh (1944-2020) qualified as a physician from Kolkata in 1969 and worked as a surgical specialist after he emigrated to the UK in 1971. But perhaps being the son of Nabendu Ghosh, he had always nursed his literary side and, post retirement, he took to pursuing his interest in translation.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles