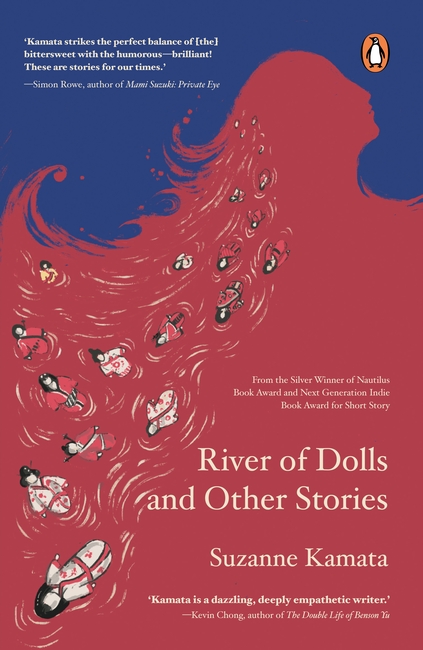

Photographs and narrative by Suzanne Kamata

When I first arrived in Japan over thirty-five years ago, one of the first places that I visited was the Iya Valley, deep in the interior of Tokushima Prefecture. It wasn’t easy to get there then, and it’s not easy now. From Tokushima, there are no trains – only very occasional buses, or you can brave the narrow, twisty mountain roads sans guardrails and drive on your own. At the time I visited, I recall no restaurants or hotels, but apparently some abandoned houses have been refurbished as high-end inns.

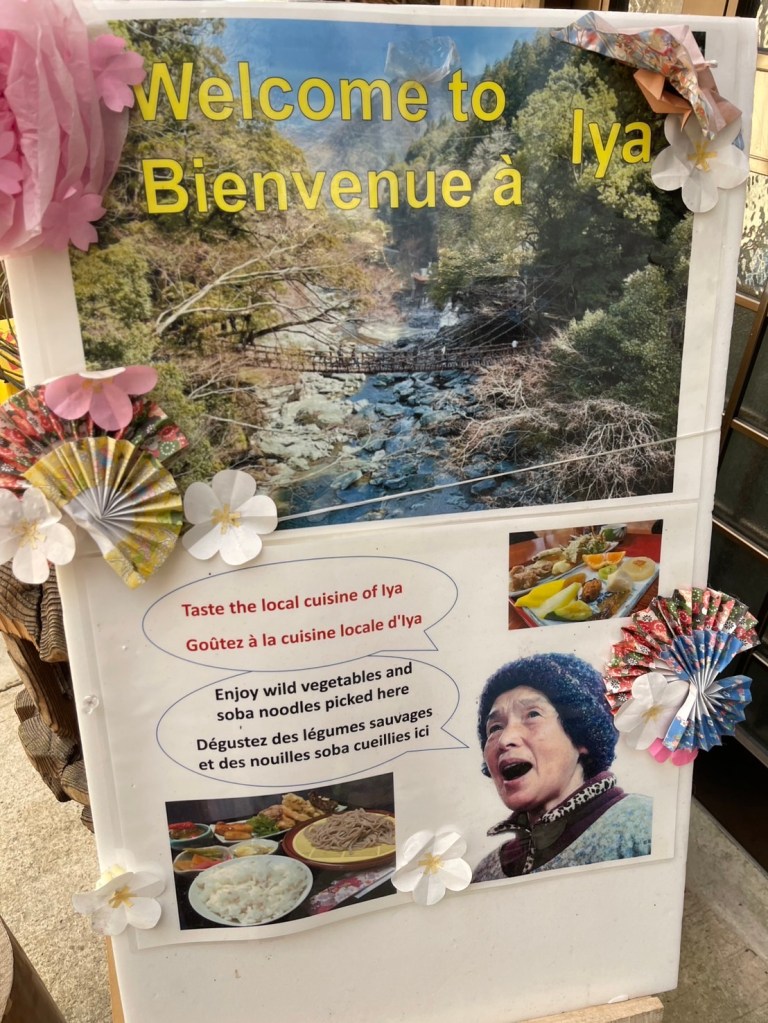

The Iya Valley attracts adventurous travelers who are up for white-water rafting on the river that cuts through the Oboke Gorge. Another thrill that can be had is crossing Iya Kazurabashi, the swaying vine bridge that spans the gorge. I crossed the bridge on that first visit years ago, and I remember clinging to the rope railings while taking careful steps, my heart hammering all the while.

The vine bridge is periodically reconstructed, but the original was said to have been created by aristocrats who had fled the capital of Kyoto. The Heike clan, who have been immortalised in the Japanese literary classic Heike Monogatari, were defeated by the Minamoto clan in the Genpei War (1180–1185) at the end of the Heian Period. They found the wilds of Shikoku to be the perfect hideout. Their descendants continue to live in the area.

I found this story incredibly fascinating. As a university student, I had been captivated by descriptions of Heian court life – the ladies-in-waiting in their layered brocade kimono, lover’s messages exchanged in the form of poetry. As anyone who has seen the recent miniseries Shogun has noted, ancient Japan was filled with aesthetic delights. Imagine going from a wooden house with fragrant tatami mats, sliding paper doors, and an ornamental garden to an untamed mountain, probably teeming with wild boar and monkeys.

I was inspired by this place to write the short story “Down the Mountain,” which appears in my newly published collection River of Dolls and Other Stories. I blended ancient history with the Japanese folktale “Kaguyahime,” or “The Moon Princess.” I was also influenced by reports that I had read of the forced sterilisation of Japanese women who were mentally ill. The story begins like this:

You say that you want to leave this mountain, daughter, and I know that your will is strong. For you, there is not enough of life in selling fish-on-a-stick or serving noodles to strangers. You look at the swaying vine bridge and see a magnet for tourists, those busloads of people who come up from the city, filling the valley with sounds of laughter and loud voices. I will not stand in your way, but before you go, there are some things that you must know.

Last week my husband, who is newly retired, took a trip to the Iya Valley as a tour-guide-in-training. While I was at work, he crossed the bridge and was treated to thick udon noodles in broth and a sampling of teas grown on the mountain. A local woman sang a traditional song to the group of visitors.

“Have you ever been to Iya?” he asked me when he’d returned home.

“Yes,” I told him. “Long ago. As a matter of fact, I even wrote a story about it.”

Suzanne Kamata was born and raised in Grand Haven, Michigan. She now lives in Japan with her husband and two children. Her short stories, essays, articles and book reviews have appeared in over 100 publications. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize five times, and received a Special Mention in 2006. She is also a two-time winner of the All Nippon Airways/Wingspan Fiction Contest, winner of the Paris Book Festival, and winner of a SCBWI Magazine Merit Award.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International