On the morning of July 30, a huge landslide occurred at Mundakkai, in the mountainous district of Wayanad, Kerala, India. 282 people have been confirmed dead and many hundreds are still missing. It is the worst landslide in the history of Kerala and perhaps one of the worst in the history of India. A whole village was washed away in the flood and the flow of earth and rocks. A government higher secondary school and a bridge also got washed away. The rescue operations are still going on.

According to data released by India Meteorological Department Wayanad district received as much as 7% of its entire seasonal rainfall in 24 hours (from Monday morning to Tuesday morning). The Mundakkai region received 572 mm of rainfall in the past 48 hours prior to the landslide. This clearly points to an extreme climate change-induced disaster.

Experts like Madhav Gadgil are saying that it was due to the environmental degradation that the disaster occurred. The fact of the matter is that the landslide happened inside a deep forest which was not affected by human intervention.

The disaster area belongs to the Western Ghats, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which is a very fragile ecologically sensitive area. This is also a region prone to frequent landslides. The Western Ghats starting from the Southern tip of the Indian subcontinent to the Konkan region is home to about 50 million people. In the parts belonging Kerala alone at least 5 million people live. Human habitation has caused a lot of ecological damage to the region. After the liberalisation of Indian economy, tourism has become a major industry in the region. Lots of tourist resorts have come up in the last 30 years, leading to stone quarrying in a major way. The stones from Western Ghats are used to build new roads, bridges, houses even in the lower land area and even the Adani port in Vizhinjam, Trivandrum.

If you look at the history of the Kerala part of Western Ghats, it was the Britishers who started huge tea, coffee and rubber plantations starting from late 19th century. It has caused huge environmental degradation in the region. Tata and Harrison Malayalam are the big planters now in the region. They behave like feudal lords, giving paltry sums in lease to the government and even encroach government lands to plant monocrops. The landslide affected Mundakkai also is a tea estate area owned by Harrison Malayalam company.

The farmers migrated to Wayanad and other parts of the Western Ghats of Kerala during the independence period due to the acute famine of that time. The government also promoted the migration of farmers. It is the descendants of these farmers who are killed by the landslide. They are the unsuspecting victims of unchecked development model and climate change caused by the Global North.

No place can withstand the kind of rain that was received in the landslide area. Yes, of course, wrong development model and environmental degradation has contributed to the disaster but it is not the root cause. It is the climate change caused by global warming for which the Global North is primarily responsible.

Present CO2 level in the atmosphere is 421 parts per million (ppm), which is similar to the CO2 level of Pliocene Epoch was a period in Earth’s history that lasted from 5.333 million to 2.58 million years ago. During the Pliocene epoch, CO2 levels in the Earth’s atmosphere were between 380 and 420 (ppm) during the warmest period. The global mean sea level during the early Pliocene Epoch was around 17.5 ± 6.4 meters which means that we are locked in for a sea level rise of at least 6.5 meters, 17 meters being the upper limit. Also CO2 levels in the atmosphere are rising 2.9 ppm per annum. This also means that we are moving into an unchartered territory in the climate crisis.

Most of our coastal cities will be under water very soon. Kerala which has one third of the landmass very close to the sea will be submerged under water. As the ocean warms more and more drastic climate events like Mundakkai will be a regular phenomenon. As Himalayan glaciers melt, the rivers originating from the Himalayas will dry up. Most of North India will be a desert. As the permafrost melts in the Arctic, Methane which is 28 times more potent than Carbon Dioxide will be released into the atmosphere and we will lead to a feedback loop, meaning more and more greenhouse gases will be released into the atmosphere without any human intervention. Another dangerous scenario is that as the permafrost melts, viruses and bacteria buried millions of years ago will be released into the atmosphere causing pandemics like COVID. Forest fires will be a regular occurrence in the dry seasons.

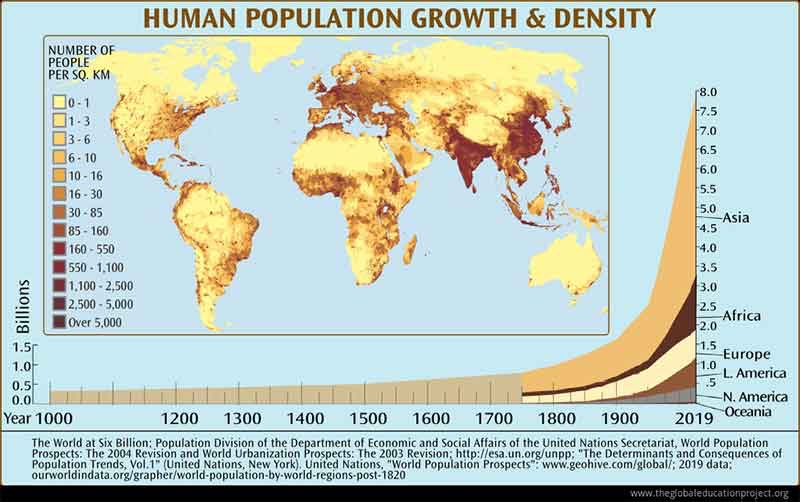

Do you think that climate change would be just weather events? No. Not at all. It will spread into social relations and human relations. We might see water wars, famines, and even civil wars in the name of nationality, ethnicity, language etc. Do you think that the present population of 8 billion people will survive the coming climate catastrophe? I think it will not. Many researchers are saying that we are in the middle of the Sixth Great Extinction. The sixth great extinction, also known as the Holocene extinction, is an ongoing mass extinction event that is caused by human activity. It is thought to be the sixth mass extinction event in Earth’s history, following the Ordovician–Silurian, Late Devonian, Permian–Triassic, Triassic–Jurassic, and Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction events.

In the beginning of the 20th Century, the human population was only 2 Billion. Now we are 8 Billion. The huge spike in population growth that we saw recently is an aberration in human history. Nature will correct itself. That means we are going to see millions or even billions of deaths, if not in our lifetime, definitely in the lifetime of our children and our grandchildren. That means thousands of Mundakkai events will play in a loop in front of our eyes! What is most devastating is that there would be some of our dear and near ones too.

What happened in Mundakkai, Wayanad is not an aberration. It’s the new normal. It’s the beginning!

Binu Mathew is the Editor of Countercurrents.org. He can be reached at editor@countercurrents.org. This article was first published in Countercurrents.org.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are solely that of the author and not of Borderless Journal.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International