I have long been fascinated by the International Date Line, which I have never yet crossed but still intend to. I have unreasonable qualms that crossing it will change a person in some way, will project them into the past or future by a day and that some part of them will always remain displaced from the present. Even if they cross the line again in the opposite direction, they won’t entirely be back in alignment with themselves. It is difficult to explain without resorting to vague words such as ‘soul’ and the idea is without any basis in fact anyway. Yet it is a feeling that persists beyond logical thought.

I suppose that the origins of my excessive interest in the Date Line can be found in one of Jules Verne’s best novels, Around the World in Eighty Days, a book with one of the best twist endings ever devised. Phileas Fogg the explorer makes a bet that he can circumnavigate the Earth in only eighty days and thanks to an unfortunate set of circumstances he fails by one day. Or does he? He has crossed the Date Line from the east in order to enter the western hemisphere and thus has gone back in time one day. When he realises this fact, he uses the extra day to win the bet. Geometry saves him.

For a long time, I wondered why Verne wasn’t praised more highly for this brilliant plot device, but now I ask myself if it wasn’t a conceit he borrowed from Edgar Allan Poe, of whom he was a great admirer. Verne’s novel was first published in 1872 but thirty years earlier Poe’s short story ‘Three Sundays in a Week’ utilised the same ingenious idea for quite a different purpose. When the name of Poe is mentioned, we imagine tales of horror and bitter despair, morbid scenes, grotesque irony, but he also wrote strange comedies and ‘Three Sundays in a week’ is one of his lightest and happiest.

The narrator, Bobby, wishes to marry Kate, but her obstreperous father, Mr Rumgudgeon, is against the match while pretending to approve of it. He offers a generous dowry with his blessings but when Bobby asks that a date be fixed for the wedding, Mr Rumgudgeon replies that it will happen “when three Sundays come together in a week!”. This impossible condition is a cruelly humorous attempt to forestall the wedding. But Bobby is a clever young man. He knows a way in which the unfair condition can be met.

He arranges a dinner for himself, Kate and her father, and two guests, both of them sea captains who had lately returned from voyages around the world. The crucial point is that Captain Smitherton and Captain Pratt sailed in different directions while circumnavigating the globe. The dinner is held on a Sunday, but it is only Sunday for Bobby, Kate and Mr Rumgudgeon: for Captain Smitherton yesterday was Sunday and for Captain Pratt the next day would be Sunday. Thus, the impossible condition is met. It is a week with three Sundays in it and no further objection to the marriage can be made.

Poe was very clear in his mind about the technicalities of time difference in such voyages, as was Verne, but confusion about east/west crossings of the Line forms one of the recurrent absurdist jokes in W.E. Bowman’s The Cruise of the Talking Fish, in which the crew of a pioneering raft accidentally disrupt, at great cost, the launching of an experimental rocket from a remote Pacific island. This book was published in 1957 (one century after the midpoint date between Poe’s short story and Verne’s novel). It is a magnificent comedy that manages to make the reader doubt their own knowledge of how the Date Line works. And in truth the mechanics of the crossing still confuse me.

Yet another novel that utilises the Date Line and the oddities surrounding it is Umberto Eco’s The Island of the Day Before in which a becalmed sailor on a ship near an island that lies on the other side of the Line indulges in speculation as to the physical and metaphysical significance of our conventions of time. The island is unreachable but remains as an anchor that tethers his mind to the topic and he is unable to stop wondering (and extrapolating this wonder) until flights of fancy turn into mathematically-based obsessions. There is always the lurking suspicion that the Line is not just a human convention but something true that is now embedded in nature as a thriving paradox.

Deep down, I still believe that crossing the Line is an act of time travel, not only in terms of human timekeeping but also in relation to the natural world, so that a man who sails into tomorrow can find out the news of the day and learn such things from the newspapers or radio as to who has won a cricket match, then recross the Line in the opposite direction and lay bets on that team, raking in huge winnings. Or a man who has suffered an accident and is badly wounded can be carried back one day into the past, where he is well again and when the following day dawns, he can take evasive action.

I know that none of this is true, but I feel it is right nonetheless, and I have written my own stories in which the Date Line features, one of them being ‘The International Geophysical Ear’, which is about a gigantic ear positioned on the Line itself that can hear both backwards and forwards in time, and another being ‘The Chopsy Moggy’, concerning a talking cat who unfortunately turns up late for an inter-species conference that will determine the future of humanity. There are others and undoubtedly more will be written.

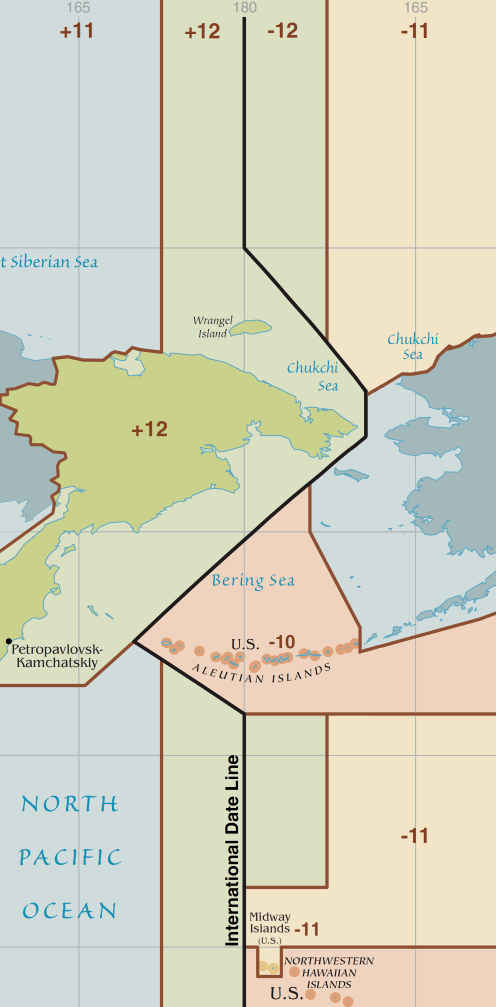

The Date Line has been host to rather strange happenings in reality as well as in fiction. On the map, it is no longer a straight line that follows the longitude of 180 degrees east and west. It veers abruptly to avoid landmasses, taking wide detours around islands. But once it deviated not one inch. It speared through the atolls and islands it encountered, dividing them in half, so that a person had the opportunity of standing with one leg in today and the other in yesterday or even tomorrow. Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean, the last dwelling place of woolly mammoths (still around when the pyramids were being constructed in Egypt), was one of these special places. Three Fijian islands too: Vanua Levu, Taveuni and Rambi, where unscrupulous plantation owners forced workers to cross the Line on Sundays to prevent them having a day off.

There is also the interesting fact that the equator crosses the Date Line and that a point therefore exists where it is summer and winter simultaneously while also being today and tomorrow (or yesterday). The SS Warrimoo was a ship that routinely travelled between Canada and Australia. On the last day of December 1899, the ship was very close to the point where the equator meets the Date Line and Captain Phillips realised that if he positioned the SS Warrimoo exactly on that point, something very curious could be achieved. He gave instructions for this to happen and on the stroke of midnight his vessel lay at 0 degrees latitude and 180 degrees longitude. Magical coordinates…

The forward part of the ship was now in the southern hemisphere and thus in summer while the rear remained in the northern hemisphere and in winter. Half of the SS Warrimoo was in the year 1899 (December) while the other half was now in the year 1900 (January). Captain Philipps was skipper of a vessel that was in two different days, two different months, two different seasons, two different hemispheres and two different centuries. Of course, the objection can be raised that December 30 is not the last day of a year. But the Captain waited until midnight before reaching the miracle point. December 31 did come but it flashed past in less than the blink of a mermaid’s eye. The ship leapfrogged an entire day, or at least the vast majority of it.

My hope is that there was a copy of Around the World in Eighty Days on board the ship when it made that spectacular crossing, or maybe a collection of the short stories of Poe. It is highly unlikely this was the case, of course. And I have just now had another thought. Suppose you are reading Verne’s novel on a ship that crosses the Line in an easterly direction. You have been reading it all day and have reached the last few chapters. Suddenly the ship crosses the Line and you are back in yesterday and find yourself only on the first page again. You might be frustrated not to know the ending to the book. Let me assist you. The hero and the heroine do get married.

Rhys Hughes has lived in many countries. He graduated as an engineer but currently works as a tutor of mathematics. Since his first book was published in 1995 he has had fifty other books published and his work has been translated into ten languages.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL