Narratives and Photography by Suzanne Kamata

FAWE Girls’ School Gahini is in the Kayonza District of Rwanda, up a bumpy red-soiled road, on a hill overlooking acres of green. Various kinds of trees and shrubbery decorate the campus, which is made up of several small buildings painted yellow and roofed in red connected by walkways. Some are painted with murals or words extolling the importance of education. The outer wall of the Science Lab, for example, features a detailed diagram of the digestive system.

A male teacher in a white lab coat comes out to greet my three Japanese traveling companions and I as we alight from the air-conditioned Prado. Our driver Eugene, hired for this week by my colleague Satoshi, remains behind.

We have traveled here from Naruto, on the Japanese island of Shikoku, where two of us are professors and two, graduate students at a small teacher’s college, for a one-week research trip. Satoshi is going to conduct a survey on metacognition in solving math problems. This is part of an ongoing project for which he has visited Rwanda several times already. Last year, when he was about to embark on his trip, I mentioned that I had always wanted to go to Africa. Without hesitation, he said, “Let’s go!”

Of course, it was impossible for me to join him on such short notice, but he checked in with me periodically, telling me the dates of his next trip. I assured him that I was still eager to accompany him. For years I had included my dream of visiting Africa in my first day self-introduction to incoming students. Here was my chance.

I am not a math professor. I have an MFA in creative writing, but I have few chances to teach Japanese students how to write poems and short stories. Mainly, I teach English conversation, and academic writing courses. In the one class I devote to non-academic writing, an elective, I am lucky if even one undergraduate enrolls. Last year, the class included a visiting teacher from the Philippines and a graduate student, both of whom were auditing the class. Even the aspiring English teachers at our university mostly hate reading and writing. If it isn’t manga in Japanese, forget it! I keep a variety of popular novels in my office and press them into students’ hands when they ask me how they can improve their TOEIC[1] scores, but I feel victorious if even one student a year comes back for more.

During the trip, we would be visiting schools, and I would have the chance to conduct a few lessons. We would be visiting a private girls’ boarding school on the second day.

“You can do whatever you want,” Satoshi assured me.

Mostly, what I knew of Rwanda was from media reports about the 1994 genocide in which over a million Rwandans from the Tutsi ethnic group were killed by fellow Rwandans who identified as Hutu. I’d seen movies about the genocide, such as Hotel Rwanda, which the director of one of the memorials we visited would declare “a scam,” and read several books by the acclaimed Rwandan writer, Scholastique Mukasonga, who lost 37 family members in the massacre.

I boned up on education in Rwanda and found that as in some other African nations, such as Kenya, the country didn’t have much of a reading culture, although efforts are afoot to change that. In the epilogue to her poetry collection, Requiem, Rwanda, Laura Apol writes that in April 2009, at the International Symposium on the Genocide against Tutsi, the prime minister spoke of “the historical and literary necessity of having survivors not only tell their stories, but for the sake of history and art, write their stories as well.” Apol conducted writing workshops through a writing-for-healing project to help survivors and perpetrators process their grief and trauma. She’d helped Rwandans develop their writing over a week. I only had 30-40 minutes. Maybe I could get them to write a haiku.

Although there is still occasional violence by so-called Hutus against Tutsis (now simply Rwandans, according to their documents), the atrocities — which made up the genocide — occurred thirty years ago. The girls that I would be meeting hadn’t been born yet. I didn’t want to dwell on that sad historical event. I wanted to encourage Rwandan joy.

I prepared a PowerPoint presentation on haiku with photos, choosing examples that I thought would appeal to teenaged girls — a poem about eating ice cream, another about meeting a boy with “pirate eyes” on a beach, a poem featuring robots and a rainbow. I also included a sad haiku about violence against children in the United States, wanting to give them permission to write about tragedy, if they really wanted to.

I was hoping that they would write distinctly African poems, maybe featuring the gorillas that lived in the Western region, or the trees bearing mangoes, bananas, and avocadoes that seemed to grow everywhere. Perhaps they would write about the many people I saw bringing yellow plastic jerry cans to the river to gather water for daily use, the vendors of kitenge cloth in the markets, or the women who balanced loads upon their heads, or tended the fields with their hoes. They might write about the goat that they had sold to pay for their education, or the wild animals they’d seen on safari in Akagera National Park. But maybe all these things were cliches of Africa. I would not suggest these topics, would not insist that they reinforce my stereotypes.

On the day of the school visit, we are introduced to the smiling head teacher, a tall man who tells me that he has written both haiku and waka, the traditional five-lined Japanese poem. He seems bemused by our presence at his school. Nevertheless, he is affable and game to have us try to teach some girls something about Japan.

We are led to a dimly-lit classroom with four long tables. Laptops for each student’s use are on the tables connected to a power source. The English teacher, another man in a lab coat, sets up a projector, and I hand over my USB drive.

The girls file in, sit down, and automatically open the laptops. Their hair is shorn, and they are wearing white short-sleeved shirts, pleated gray skirts, and matching neckties. To get things started, Satoshi introduces our group and asks a few what they want to be in the future.

“Surgeon,” says one.

“Banker,” says another.

I remember how, when I had first arrived in bubble-era Japan as an assistant high school English teacher, the female students had replied “A good wife and mother.”

Okay. So these girls are good at English, and they are ambitious.

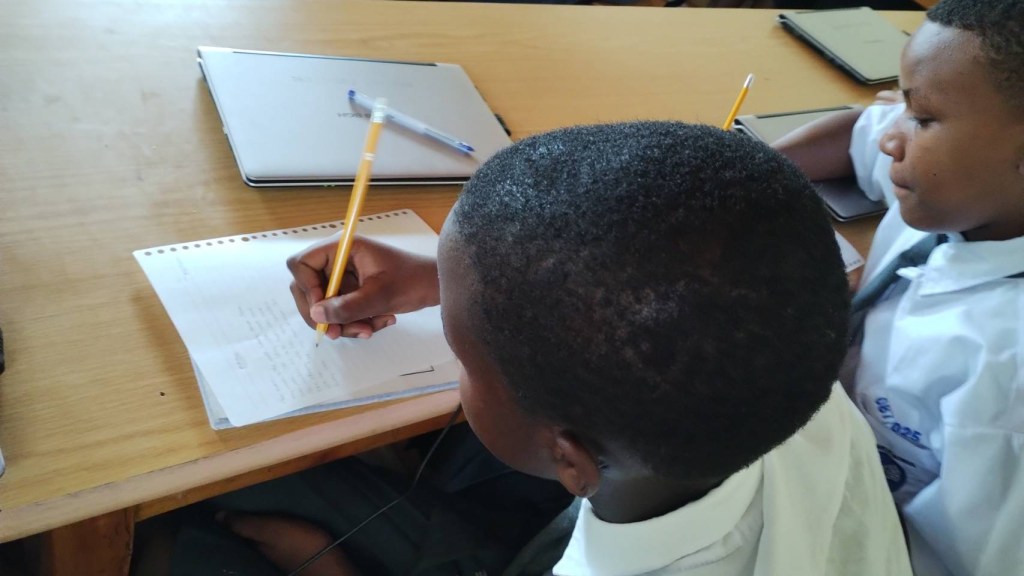

“Please close your laptops,” I say. I personally prefer to write poetry by hand, and I am always worried about students using generative AI, so I have brought pink and lavender pencils, which I bought at Daiso and sharpened back in Japan, and loose leaf lined paper.

I introduce myself briefly, explaining that I am an American, but I married a Japanese man, and have now lived in Japan for over thirty years. I also tell them that I am a writer, and I have brought some books by myself and others which I will donate to their library.

“A haiku,” I tell them, “is a short Japanese poem, usually consisting of 17 syllables, and including a kigo, or seasonal word.”

Their forty or so faces are turned toward me, but I can’t tell if they are engaging. When I ask if any of them have ever written poetry, four raise their hands. When I ask if they have ever written haiku, or even heard of it, the hands stay down. I go through my PowerPoint, noting their interest in a poem about Girls’ Day in Japan, on which families with daughters display ornate dolls representing the emperor, empress, and court.

“And now it’s your turn,” I tell them when I reach the last slide. “Let’s try to write a haiku.”

I ask them to think of an event, or a moment, and write whatever related words come into their heads over the next five minutes. They begin to scribble. When the timer on my phone goes off, I remind them that it’s okay to ignore the five-seven-five syllable rule, and that they don’t have to stick to seasonal topics. I tell them that if they are having trouble, they can use a poem from the PowerPoint as a template.

While they ponder and write, I wander along the rows, looking over their shoulders. I’m pleased to see that some have taken my suggestion to model their poem by one by Masaoka Shiki, about eating and drinking with friends on an autumn evening. But pizza? Ice cream? I’m a little disappointed that they didn’t use a more African dish, like brochettes, and banana beer. Then again, that is just my stereotype. Rwandans eat pizza, too.

Instead of writing a haiku, one girl writes a longer poem, which is clearly about the genocide. I realize that even though I want to encourage them to move on, to look to the future, to laugh and dance and celebrate, the trauma caused by the slaughter persists, hanging like a cloud over the country. Their parents probably lived through it, and there are reminders everywhere. Everyone has a story. Our driver tells me later that his father, sister, and brother were murdered. Rwandan students visit genocide memorials on school excursions as part of their education, just as Japanese students visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Peace education is deemed very important here, and, during this time of division, I can’t help thinking that it would be good in my own country as well.

At the end of the lesson, I tell them that what they have created belongs to them. I want them to keep their poems, but I also want to read them. I ask them to copy their haiku onto another piece of paper and give it to me.

“I hope you will keep writing haiku,” I tell them, my grandiose idea of promoting Rwandan literature in mind. I tell them of where they can send their poems for publication to an international audience. We pose for a group photo.

Later, I bring my books to the library.

“Bonjour,” says the nun librarian, who must have been schooled when French was the official medium of education.

I had not realised that this was a Catholic institution. I hope that no one takes offence that one of the books I am donating, which has been banned in some places in the United States, is about a Muslim girl. In another, a novel by a contemporary Zimbabwean writer, a teenaged girl confesses to having had premarital sex. A character is one of my own novels is a gay figure skater.

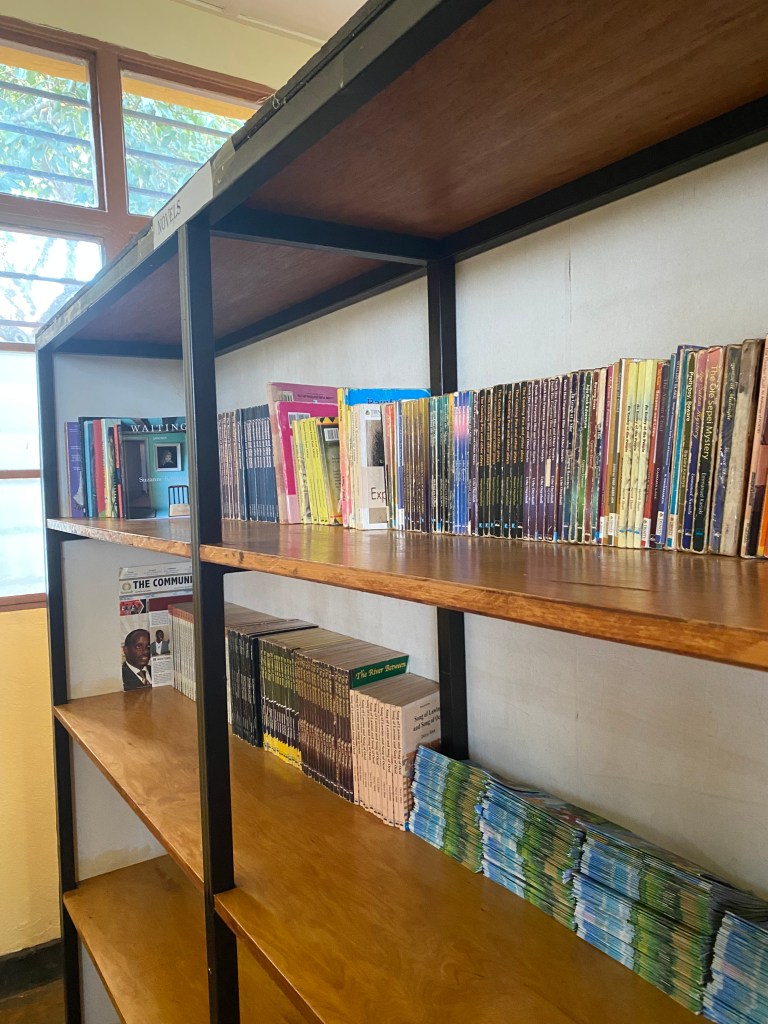

The nun accepts the books graciously and tells some tag-along students to place them on the fiction shelf. I stand back, noting that the ones already there are old and worn. Perhaps they do most of their reading online? In any case, there are no young adult novels for girls, nothing published in the past few years, and I know how expensive imported books are.

“I hope you will read them,” I say, thinking of my students back in Japan who hate to read.

“We will,” the girls promise.

I imagine a single girl, coming upon these novels and greedily devouring them one after another, perhaps seeking out more, and then beginning to write her own stories. I imagine coming across a novel in a bookstore written by a girl who grew up in Kayonza, who attended the FAWE Girls’ School Gahini. I imagine reading that book and posting about in on Instagram. And then I try to let go of my expectations, and say “murakoze,“ which means “thank you” in Kinyarwanda, and “goodbye.”

Hamburgers and fries

Speakers blare Billie Eilish

--lunch in Kigali

A Haiku by Suzanne Kamata

[1] The Test of English for International Communication

Suzanne Kamata was born and raised in Grand Haven, Michigan. She now lives in Japan with her husband and two children. Her short stories, essays, articles and book reviews have appeared in over 100 publications. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize five times, and received a Special Mention in 2006. She is also a two-time winner of the All Nippon Airways/Wingspan Fiction Contest, winner of the Paris Book Festival, and winner of a SCBWI Magazine Merit Award.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International