By Meredith Stephens

On our final day in California, we were looking forward to making the journey to Kings Canyon to see the largest tree in the world, a giant sequoia 87 metres tall. We packed the car with eight pieces of luggage destined for Australia, into Alex’s 1993 Ford Explorer. It had served us faithfully for several hundred miles of touring in California for the previous weeks. We headed up the winding mountains to Kings Canyon, dotted with live oaks and cattle in the foothills. We were heading up a particularly steep section of the road when the engine faltered. Alex urgently pressed his foot on the accelerator but the car refused to budge.

“I’ll try and push it,” I offered.

I positioned myself to one side of the rear of the car. If the brakes failed, I did not want the car rolling back and flattening me. The car did not respond to my urgings so I gave up. I noticed cars ascending the mountains at speed, and the blind corner ahead. I decided to walk uphill so that I could signal the cars coming up the hill to warn them of oncoming traffic around the corner. When there was a car descending the hill on the other side, I put up my hand to warn them to stop until it was safe. About twenty cars passed us this way, until one driver noticed our plight and decided to help us. He stopped at the turn-out, and two elderly couples alighted from the car.

“Hasn’t anyone stopped to help you?” the driver asked.

“You’re the first,” I replied.

The two men walked towards the car to help push it twenty metres to the turn-out.

“John!” called out his wife, trying to stop him. It obviously wasn’t safe for a man in his seventies to push a heavily laden car up a mountain ahead of oncoming traffic.

Meanwhile, a man in his thirties had joined the party. Another car stopped on the other side of the road. Two burly men with tattoos crossed the road to help push the car to safety. Alex, the elderly men, the younger man, and the burly men, joined forces to push the car to the turn-out. The car slowly responded and was eventually positioned off the road. The burly men crossed the road to return to their car, and the elderly men returned to theirs. The younger man remained with us.

Alex tried to call the automobile service but his phone had no reception.

“Can I borrow your phone?” he asked the younger man.

“Sure. By the way, it might be quicker to call a tow truck. I suggest getting a tow-truck from Reedley, because you will be able to rent a car there.”

We called the tow truck company in Reedley and they agreed to come in two hours. The young man, who turned out to be an off-duty ranger, took his leave. We grabbed our picnic items from the car, and headed downhill to the shade of a large live-oak, while we waited for the tow truck. Lying on the grass under the cool shade of the live-oak, enjoying our picnic items, I could almost forget that we were in a crisis. After an hour or two we thought we needed to be visible from the road for the tow-truck, so we returned to the punishing heat road-side, and soon the tow truck appeared. The driver expertly loaded the car onto the truck, and invited us to join him in the front.

“Careful. It’s very high up,” he warned.

I stretched my legs to reach each step to get into the front of the truck, and sat in the back seat, while Alex sat next to the driver.

Sitting in air-conditioned comfort high up with a view down the mountain was such a contrast to sitting in the old car, straining up the mountain. We reached the plains and passed through the hamlet of Squaw Valley before reaching Reedley. With only minutes to spare, we picked up a rental car, removed a few items from the Explorer, and drove back up the mountain. We wound our way past where the car had broken down, into the National Park, through dense forest and charred remains of forest fire several years ago. We followed the signs to our lodge, but our break-down had cost us several hours, and we did not have time for sights that evening.

That evening, Alex checked the passports to confirm they were at hand for our departure to Australia the following evening. They were not in their usual place. We searched our other bags. Then we retrieved bags from the car and searched them too, to no avail.

“We’ll have to call the consulate and get temporary passports,” I suggested.

“First, we will have to retrace our steps. Maybe they fell out when the car broke down. Maybe they are still in the Explorer,” suggested Alex.

That night Alex could not sleep, worrying about the passports. What if we could not return to Australia the next evening and had to buy new tickets? The next morning he was still worried.

“We’ll have to look for the passports, retracing our steps from yesterday. We have no time to see the tallest tree in the world.”

“Do we have time to see the third to tallest tree in the world?”

“Yes. That’s only a fifteen minute detour.”

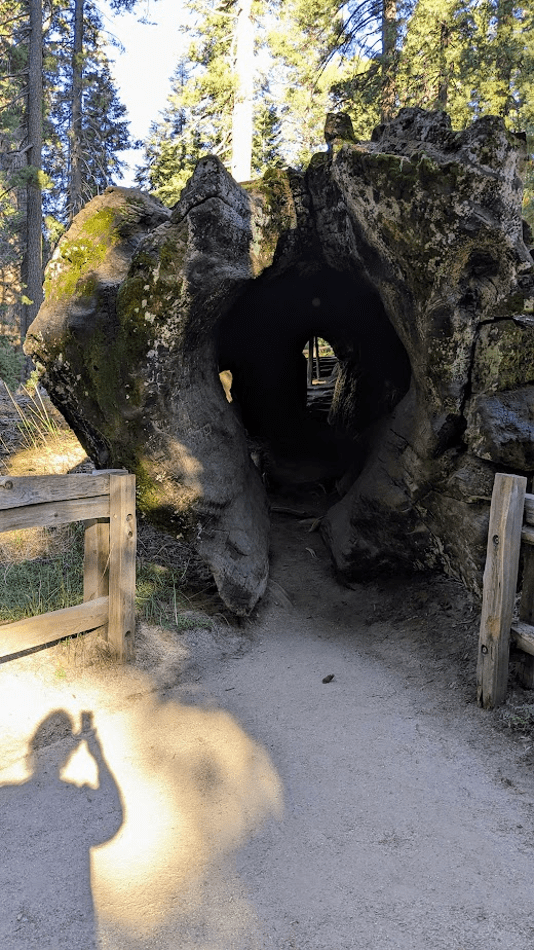

We drove to see the third to tallest tree in the world. As I started walking in the forest I immediately felt both exhilarated and relaxed. These giant trees provided a protective canopy and their scent sent a rush of well-being through my body. I was satisfied. Did I really need to see the largest tree in the world? Yes, but that would have to wait!

We hurried back down the mountain to search for the passports. We could not risk the possibility of not finding them just because of sightseeing. We reached the area of our break-down, and combed the grassy hill carefully in search of the passports, to no avail. Then we wound our way back down the mountain to the tow truck business. I received the keys from the office, opened the car door, and there were the passports on full display.

“Shall we go back to Kings Canyon to see the largest tree in the world?” I asked Alex.

“It will be ninety minutes to get back to the National Park, and then a five hour drive to the airport in LA.”

“I really want to see the tree, but I can’t face over six hours in the car. I guess we should head for the airport.”

“If we had known that the passports were here, we could have gone and seen the tree while we were still in the park,” lamented Alex.

With passports in hand, we did not need to visit the consulate to be issued temporary ones. We could catch the plane as planned. We were not able to see the tallest tree in the world, even though we had driven up the mountain twice. There was some consolation in the fact that the tree would be waiting for us, in years to come, when we had the opportunity to return to our beloved California.

Meredith Stephens is an applied linguist from South Australia. Her work has appeared in Transnational Literature, The Muse, The Font – A Literary Journal for Language Teachers, The Journal of Literature in Language Teaching, The Writers’ and Readers’ Magazine, Reading in a Foreign Language, and in chapters in anthologies published by Demeter Press, Canada.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International