By Charudutta Panigrahi

If language were a haircut, “saloon” got a buzz cut and a blow-dry and came out as “salon.” That change in spelling is the visible tip of a larger style transformation: one rough, male-only ritual space has been trimmed, straightened, scented and repackaged into a gleaming, multi-service, mostly woman-centred retail experience. Along the way, the loud, fragrant, argument-heavy mini-parliaments of small-town India — the saloons — have been politely ushered into warranties, playlists and polite small talk.

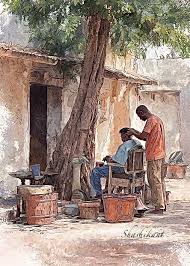

Barbers in India are almost as old as conversation itself. The profession of the barber — the nai or hajam — is embedded in pre-colonial life: scalp massage (champi), shaves, tonsure at rites of passage, and quick fixes between chores. These services were usually delivered in open-fronted shops or under trees, with tools that were portable and livelihoods that were local.

The “saloon” as a distinctive, Western-flavoured, male gathering place began to consolidate during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Port cities and colonial cantonments — Bombay (Mumbai), Calcutta (Kolkata), Madras (Chennai) — saw the rise of dedicated shops selling not only shaves and haircuts but also imported tonics, straight razors and a distinctly public atmosphere shaped by newspaper reading, debate and gossip. Over time, that form blended with older local practices and spread inland. By the mid-20th century, the saloon — a recognisable, chair-lined, mirror-fronted social stage — existed in towns from Kashmir to Kanyakumari and from Gujarat’s chawls to Assam’s market roads.

So ancient barbering traditions fed into a colonial-era intensification of the barbershop as public forum; by the 1950s–70s, the saloon as we remember it was firmly a part of India’s social furniture. The precise start date is a quilt of custom and commerce rather than a single founding ceremony — and that is part of the saloon’s charm.

Walk into a saloon in Nagpur, Nellore, Shillong or Surat and you’ll notice an uncanny resemblance. The reasons are simple and human:

- Low price point: Saloons survive on quick volumes and walk-ins. That encourages many chairs, fast turnover, and layouts that invite waiting men to talk rather than sit quietly.

- Ritual services: Shave, cut, champi. These are short encounters that thread customers through the same communal space repeatedly — ideal for gossip to collect and ferment.

- Social role: The barber doubles as ear, counsellor, news-disseminator and crossword referee. That role is culturally consistent across regions: a saloon’s psychic geography is the same whether the tea is masala or lemon.

The result is that a saloon in Kutch and a saloon in Kerala will differ in language, politics and local jokes — but both will produce that same satisfying racket of opinion, repartee and advice. They are India’s unofficial, peripatetic fora for public life.

Enter the salon: padded seats, curated playlists, appointment-booking and a menu so long it reads like a restaurant wine list (colour, rebonding, keratin, facials, pedicures, threading, and sometimes a minor festival of LED lights). A couple of business realities did most of the heavy lifting:

- Women’s services earn more and recur more often. Regular facials, hair treatments and beauty routines translate into steadier, higher bills. The money follows the customer, and the space follows the money.

- Franchising and professional training created standardized staff who follow brand scripts — which tighten conversation and reduce the barber-confessor vibe.

- Unisex salons consolidated footfall, but that consolidation shrank male-only territory. Men who once had a semi-public living room now sit in chic, quieter spaces that discourage loud, extended debate.

The practical upshot: the saloon’s boisterous mini-parliaments were replaced by stylists with laminated menus, muted background music and an etiquette that favours privacy over political salvoes.

What we miss (and what we gained)

We miss the moralisers, the wisecracks, the boisterous consultancy of unpaid experts who knew which councillor was friendly with which shopkeeper and which wedding was scandalous; the loud education in rhetoric and local affairs; the bench-seat apprenticeship in how to perform masculinity in public.

We gain in expanded choices for women, more professional hygiene and techniques, new livelihoods for trained stylists (especially women), and spaces where people can pursue personalised care without the social cost that used to attend public rituals.

It’s not a zero-sum game — but it does reorder who feels proprietorial about public grooming spaces. The new economics say: she who pays more — and pays more often — gets the say.

Not all saloons are extinct. In smaller towns they still hum. In cities, they’ve evolved into hybrid forms:

- Old-school saloons persist where price sensitivity and cultural habit remain strong: walk-ins, communal benches, loud conversation and a barber who’ll recommend both a haircut and the correct candidate for local office.

- Nostalgic barbershops in urban pockets lean into the past with “vintage” decor, whiskey-bar vibes and sports on TV — except now they charge a premium and call the barber a “grooming specialist.”

- Some entrepreneurs stage “men’s nights” or open-mic gossip hours in neighbourhood shops, trying to recapture the civic pulse while keeping the modern business model.

If you want the old saloon spark, look for places without appointment apps, with too many phones in sight but none in use, and with a tea flask on the counter.

What’s lost isn’t only a loud, male-only gossip pit; it’s a training ground for public argument and a place where local memory was kept live and messy. The saloon taught people how to spar without a referee; the salon teaches how to look good while being politely neutral. If you mourn for the saloon’s barbed banter, you can grieve — but also take action: host a “Salon for Men” in your local café, revive a community noticeboard at the barber, or convince your neighbourhood salon to schedule a weekly “open-chair” hour for community talk (and maybe offer tea).

And until then, if you miss the salty, pungent chorus of small-town democracy, go to any saloon that still has a kettle on the stove and a barber who knows the mayor’s schedule by heart. Sit down, get a shave, and watch a mini-parliament assemble around you. You’ll leave clean-faced, better informed, and maybe a little animated — exactly how democracy used to feel.

.

Charudutta Panigrahi is a writer. He can be contacted at Charudutta403@gmail.com.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International