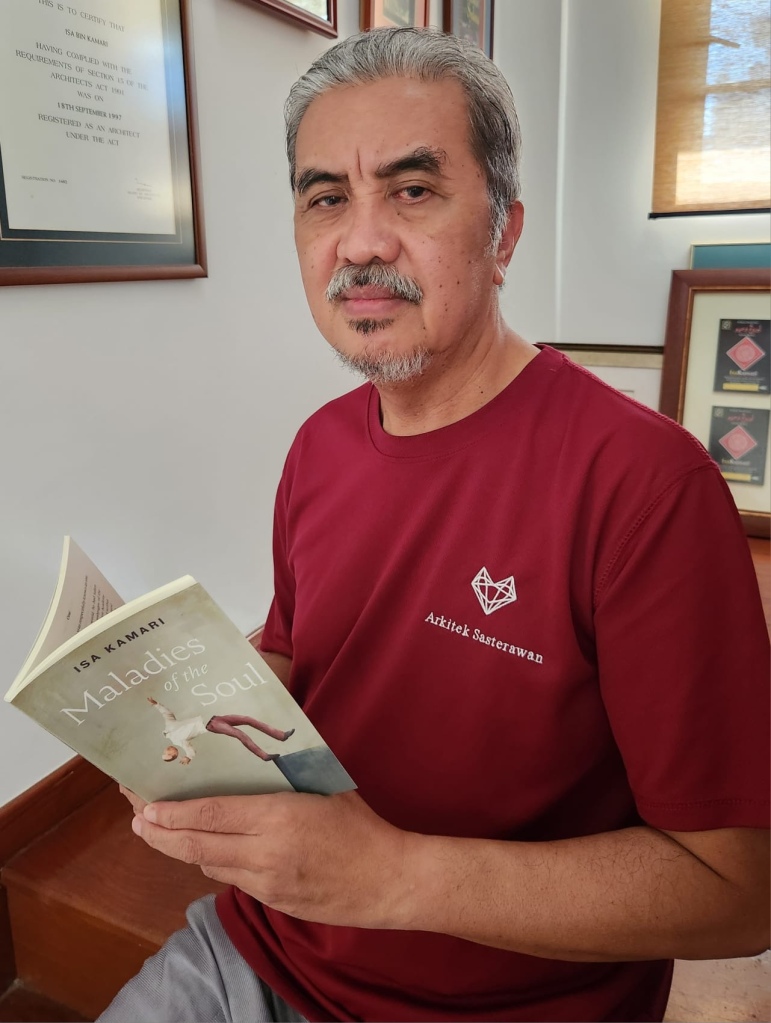

An introduction and a conversation with Isa Kamari, a celebrated Singaporean writer

Isa Kamari is a well-known face in the Singapore literary community. He has won numerous awards — the Anugerah Sastera Mastera, the SEA Write Award and the Singapore Cultural Medallion, the Anugerah Tun Seri Lanang. He has been part of university curriculums and has written for the television. With 11 novels, nine of which have been translated from Malay to English — and some into more languages like Arabic, Mandarin, Urdu and Turkish, French, Russian Spanish — three poetry books, plays and one novella written in English by him, one can well see him as a leading voice in literature on this island that seems to have grown into a gateway for all Asia.

Kamari’s writings dip into his own culture to integrate with the larger world. The most remarkable thing about his works, for me has been the way in which he has brought the history of Singapore from the Malay perspective into novels and made it available for all readers. The most memorable of these actually gives the history of the time around which the Treaty of Singapore was signed between the British and the indigenous ruler in 1819, handing over the port to Raffles, the treaty that was crucial to the founding of modern Singapore. The novel is named after the year of the treaty.

Other novels like Song of the Wind , Rawa and Tweet — all bring into perspective how the local Orang Seletar integrated into the skyscrapers of Singapore. We can see in his writings how the indigenous moved to be integrated into a larger whole of a multi-racial, multi-religious accepting modern city. One of his novels, One Earth (1999), is like an interim almost, set during the Japanese occupation in Singapore. The narrative dwells on the intermingling of races in the island historically. Kiswah and Intercession are novels that cry out for reforms on the religious front.

He also has novels that delve into individual journeys to glance into the maladies of the modern-day world. Whether it is faith, or career, he brings into focus the need to heal. Recently, Kamari has brought out a book of short stories, Maladies of the Soul, to focus on just this. His fifteen short stories centre around the issue mentioned in the title. In the first ten stories, he writes of old age, of mental stress, of compromises made to achieve success, of anxieties just as the title suggests. These are internal conflicts of people in a country where most have enough to eat, a house to live in and access to education for their offsprings. Then in the last five stories, he moves towards not just showcasing such maladies but also resolving, using narratives that are almost surrealistic, or poetic. They are not happy but reflective with the ability to make one think, look for a resolution. They are discomfiting narratives.

One of the last stories is given from the perspective of a silkworm — a powerful comment on the need for freedom to survive. Another has the iconic Singapore Merlion emote to an extent. The writing escapes the flaw of being didactic by its sheer inventiveness. One is reminded that this is a book by an author from a city-state which has resolved problems like poverty to a large extent. That the journey was arduous and full of struggle can be seen in Kamari’s earlier novels. But now, that people have enough to eat and live by, he takes the next step that is necessary. His stories demand not just being familiar with the issues they faced in the past, but also suggest a movement towards resolving the social problems that in a developed country can warp individuals to make them non-functional and make the society lose its suppleness to adapt and progress.

One of the stories like his earlier novel, The Tower, reflects the climb of a careerist, an architect, up a tower he has built, while recalling the compromises made. The interesting thing is the conclusions have a similar impact. And then, there is yet another story that is almost Kafkaesque in its execution, where a man turns into a bull — a comment on stock trading or people’s obsession with money and to compete?

The book needs to be read sequentially to get the full impact of his message. For, he is a writer with a message, a message that hopes to heal the world by integrating the spiritual with modernisation. In this conversation, he discusses his new book and his journey as a writer.

What makes you write? What moves you to write? Why do you write?

I need to be disturbed by events, issues and thoughts before thinking of writing anything. I would then ponder and research on the topics at hand. Only when I have my own tentative resolution of the conflicting elements, I would begin to write. Most often, my views and positions will change as I write further. In that sense writing is a form of discovery and therapy for me.

Do you see yourself as a bi-lingual writer or a Malay writer experimenting in English? You had written your novella, Tweet, in English. Later it was translated to more languages. How many languages have you been translated into? Do you feel the translations convey your text well into the other language?

Culturally, I think in Malay. English is a language of instruction for me. When I attempt to translate my Malay works into English, the writing sounds and feels Malay. Tweet is a result of a challenge I imposed upon myself to write creatively in English. The result is not bad. Tweet has been translated into Malay, Arabic, Russian, French, Spanish, Azerbaijan and Korean. I wouldn’t know how well the novella has been translated because I do not know those languages. I trust the translators whom I choose carefully.

The stories of Maladies of the Soul first appeared in Malay. Now in English. Did you translate them yourself, being a bi-lingual writer? Tell us your experience as a translator of the stories. Did you come across any hurdles while switching the language? What would you say is the difference in the Malay and English renditions?

Yes, I translated all the stories in the book. I had to overcome my own fear that the stories might end up too Malay in expression and feel. But I told myself to be true to my own voice and not be inhibited by language structure and convention. I would not know exactly the difference between the two renditions. I was just interested to tell the stories.

Is this your first venture into a full-length short story book? Tell us how novels and short stories vary as a genres in your work. How do you use the different genre to convey? Is there a difference in your premise while doing either?

I have produced just one collection of short stories. In each of the short stories, I had to be focussed on expressing concepts and philosophies on a single problem of the human condition. In my novels the concepts and philosophies are varied, expanded, more complex and layered but yet interrelated and weaved around dynamic human experiences facing common predicaments or challenges of an era.

One of the things I noticed about the book was that the stories would convey your premise better if read in order. Is that intentionally done or is it a random occurrence?

The short stories can be weaved into a novel. There is a central spine, which is my observation and philosophy of life which bind them all. The intrinsic sequence or order is not intentional, but perhaps it is the psychological thread and latent articulation of the storyteller.

Some of the stories seem to have echoes in your novels, like Kiswah and Intercession, both of which deal with crises in faith. Did your earlier novels have a direct bearing on your short stories?

I used to transform my poems into short stories, and from those write novels. The genres are just tools for me to express my thoughts and feelings. I use whatever works. I have even experimented on weaving short stories and poems in a novel. I wanted to create prose that are poetic, and poems that are capable of conveying a narrative. My latest novel, The Throne, is a result of this experiment.

Some of your stories touch on the metaphorical, especially the last five. Some of the earlier ones describe unusual or even the absurd situations we face in life. As a conglomerate, they explore darker areas of the human psyche, unlike your novels which were in certain senses more hopeful, especially Tweet. What has changed to bring the darker shades into your writing? Please elaborate.

The stories in Maladies of the Soul have a common theme of alienation in various facets and dimensions of life. As such the expected feeling after reading them is that of gloom and hopelessness. That is intentional as a revelation of the deeper and hidden fallacy of modern life that appears organised and bright on the surface. I wanted my readers to be shaken or at least moved to ponder and reflect on our current, shallow and fractured human condition. There is a better life if we were to look the other way and be more mindful and caring of each other and our environment.

I still recall a phrase from your novel, The Tower, “Festivities celebrating loneliness”. Would you say your short stories have moved towards that?

Exactly.

Why did you choose short stories over giving us a longer narrative like a novel?

It is like giving my readers bite sizes of my exploration and philosophy of life. I leave it to the readers to weave the stories into a whole, and reflect upon their own experiences, thoughts and feelings, perhaps in a more integrated and holistic manner.

What are the influences on your writing?

Life itself. Like I mentioned earlier I do not write in a vacuum. I engage life in my writing as a way of validating my ever-changing existence. I want my life and writing to be authentic and significant. Hopefully, meaningful to others too.

What can your readers look forward from you next?

I have just completed a draft of a novel in Malay, Firasat. As in all my novels, I offer a window towards healing by embracing a rejuvenated Malay philosophy called firasat which is an intuitive, integrated, balanced, lucid, harmonious and holistic way of life.

Thank you for sharing your time and your writings with us.

(The online interview has been conducted by emails by Mitali Chakravarty)

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International