Narratives and Photographs by Mohul Bhowmick

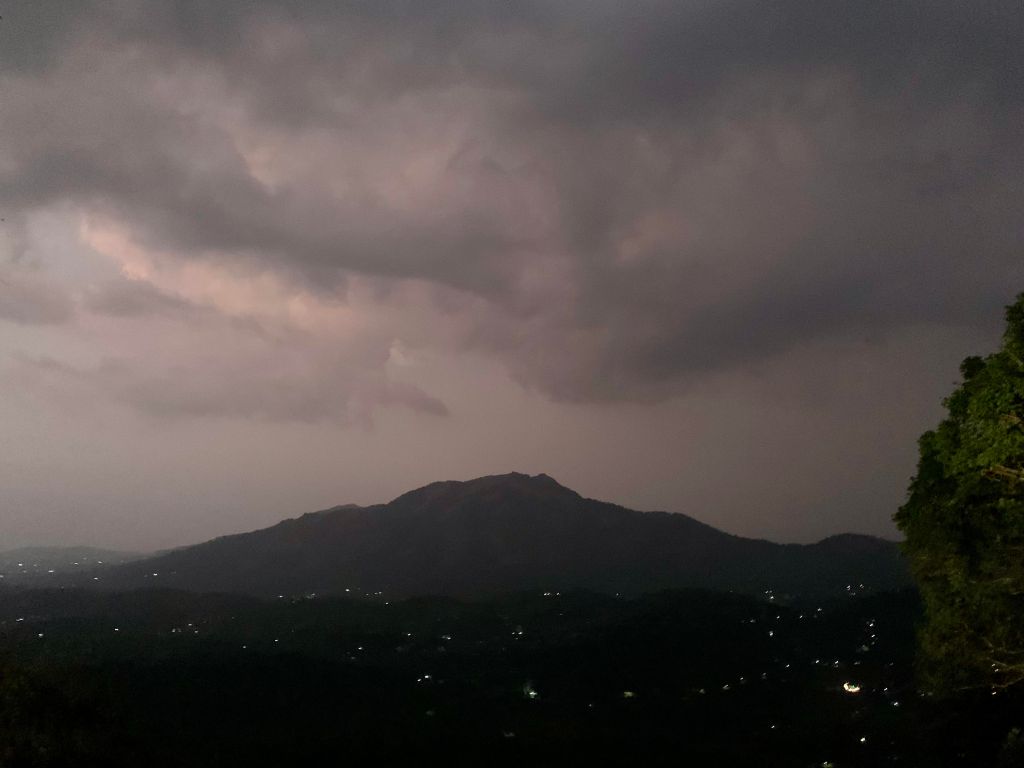

Chembra stands out imperceptibly in the background as the mist descends over its northern side. The driver of the rickety auto-rickshaw in which I make the topsy-turvy trip from Kalpetta settles to drop me at the backpacker’s hostel at Chembra’s foothills for 500 rupees. A vast tea estate stretches out for as far as the eye can see, and it is only when one edges closer to the property’s north-western precipice is any semblance of Wayanad encountered.

Originally a hospital set up by the British in the 1920s, the hostel is a renovated colonial-style structure with a vast corridor that runs parallel to its rooms. I learnt much later that the tea estate that houses the hostel is spread over 700 acres. The fall to the northwest is spectacular, with hills in the lower range of the Western Ghats basking in the late evening sun as it makes its way down to the low-country orbs of Mysore and Chamarajanagar.

It is no surprise that one has to cross Bandipur to reach Wayanad in the first place; any easier and one would have been tempted to think that one was within the anonymity of civilisation.

*

Earlier in the day, the elephants that I spotted from an unobtrusive window on the bus from Mysore seemed triumphant and exultant — for what I did not know. The egret that sat contentedly upon the shoulders of a rather guileless water buffalo winked at me as I struggled to bring my camera out of the mishmash that my backpack had become. I was reminded of an older boy with whom I never got along in school and who often bullied me for the pancakes my mother painstakingly packed.

*

I am forced to snap out of this reverie when my hostess reminds me that elephants were spotted at the southern expanses of the property a few days ago. She asks me to not step out after dark. In the common area boasting of a sit-out on a makeshift tree house, a motley crew from all hues of life rejoice at what appears to be a joint venture launched by a businessman from Bangalore and an engineer from Bombay. I join the pack and am welcomed by a loud cheer.

John, a chartered accountant who rode all the way from Coimbatore on his imported motorcycle, recounts having seen a leopard when turning in one of the several snaking curves when climbing from Kalpetta. He slurs as he articulates and his eyes appear bloodshot; I know only too well to separate the wheat from the chaff. Advait, a veterinarian from Anantapur, rebuffs everything that John says and vociferously advocates for an early dinner. He is, quite promptly, turned down.

*

The trek towards the peak of Chembra is made through the heartland of the eponymous forest range. Langurs peer out inadvertently while a flying squirrel makes an appearance from its cosmic abode. Catching sight of me and my companions’ incongruously sunscreened visages, it jumps shyly onto the double-storied Bo where it has made its home. Murali, the young forest officer who accompanies us jokes with Estelle, the German lady who quite fortuitously chooses to trek in her Birkenstock footwear, about sightings of bears in the vicinity but restrains himself when she turns ashen white.

The heart-shaped lake peeks with unabashed curiosity as we huff and puff our way up to the midway point of the trek. To our great consternation, this is where we have to end our trip as the summit of the peak is sealed off by the government. A few years ago, Murali tells us, a group of nincompoops who made it to the summit lit a couple of cigarettes to celebrate. They did not, however, stub them when they were done. What happened next is well documented — a forest fire of gargantuan scale that wiped out about 60 hectares of forest land and claimed the lives of hundreds of wild animals. The summit has been off-limits to travellers ever since.

The parched outcrops that surround the lake by no means diminish the panorama that lies to the west. A faint countenance of the vast fields of tea and paddy which fortify the district of Wayanad is visible through the mist. It is almost noon, but my companions and I find no reason to shed our coats. Specks of Mohit Chauhan’s Phir Se Ud Chala[1] fill the air; it feels as if Chembra herself has come to life.

It is not exactly wise, but we surrender to the lure of lying down on the grass and bask, cocooned by the benevolent gaze of Chembra. Dark clouds brew overhead but Begum Akhtar reassures us in her palliative voice, and it is not before the first drops fall on my forehead that I alert the others over our predicament. Unsurprisingly, I find that most of my friends had nodded off, obliged by the exercise and the accompanying iridescent breeze.

*

The descent, as always, is trickier than the climb, and we take refuge from the rain under a giant rock midway. The shelter is insubstantial for a group of ten, and we end up getting soaked to the skin anyway. Murali, rather ingeniously, offers his service raincoat to Estelle. Much to his chagrin, she declines, and continues unabated in her soaking t-shirt, Nike track pants and Birkenstocks. Someone mentions a childhood spent in the Bavarian Alps…

Dry leaves fall from the trees — these untimely showers ensure that they are not held on to their material comforts for long — and the fauna we encountered on the way up seemed to have disappeared. The langurs call out occasionally, but the mynahs respond in dulcet tones of their own.

Drenched to the core yet alive beyond measure, the rain loses significance as we meander down the trail. Consciousness makes itself felt in every cell of my body as I lumber past the sludge and try to find a foothold on the wet tracks. Awake to the moment and mindful of not slipping — essentially holding my life in my hands — I experience a pacifying sense of tranquillity that I normally associate with timing a straight drive back past the bowler on a cloudy afternoon at the Gymkhana.

Damp pathways mark our way back to the hostel. On the way, an appetising breakfast of puttu and kadala curry[2] is sought to calm our nerves. A gulp of tea, brewed from the plants of the estate on which our hostel stands, soothes and brings some warmth back into our bodies. After that, we sleep all afternoon. The 1980s restaurant at this point serves as a reputable hotbed for the exchange of accounts as fellow travellers make their way upcountry for further investigation. Krishnagiri, Edakkal, Banasura and even Ooty, among other places, feature on their itinerary. Buses out of Meppadi take the circuitous route towards Sultan Bathery via Kalpetta. A few companions remain as I make the hike back to the hostel.

Last vestiges of the raindrops from earlier in the day cling on with pride on the tea leaves. Seen from a distance as we walk up the bend onto the track that leads to the hostel’s gates, it appears as if the leaves have shed tears of their own.

The sky turns a dull shade of orange, almost as if playing testament to friendships made and attachments uncovered. I am content enough to watch the sunset over the lower Western Ghats as another pre-monsoon drizzle wafts in. Someone mentions a fresh batch of pazham pori[3] being made in the kitchen. I scramble down the tree house to beat the rush.

[1] Song from Bollywood movie, Rockstar. Translates to: He flew again

[2] Local fare. Rice cake and spicy chick pea curry

[3] Banana Fritters

Mohul Bhowmick is a national-level cricketer, poet, sports journalist, essayist and travel writer from Hyderabad, India. He has published four collections of poems and one travelogue so far. More of his work can be discovered on his website: www.mohulbhowmick.com.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International