By Hazaran Rahim Dad

Akbar Barakzai (1939-2022) was born in Shikarpur Sindh, Pakistan. He received his early Education from Karachi and later he graduated from University of Karachi. Barakzai is considered as one of the most defiant progressive voices in modern Balochi literature. His poetry reflects the objective realities of life and ambitions of his people. Boundless love for masses, profound desire for peace and prosperity, and unwavering resolve to resist and defy the tyranny are some of the commonplace themes of his poetry.

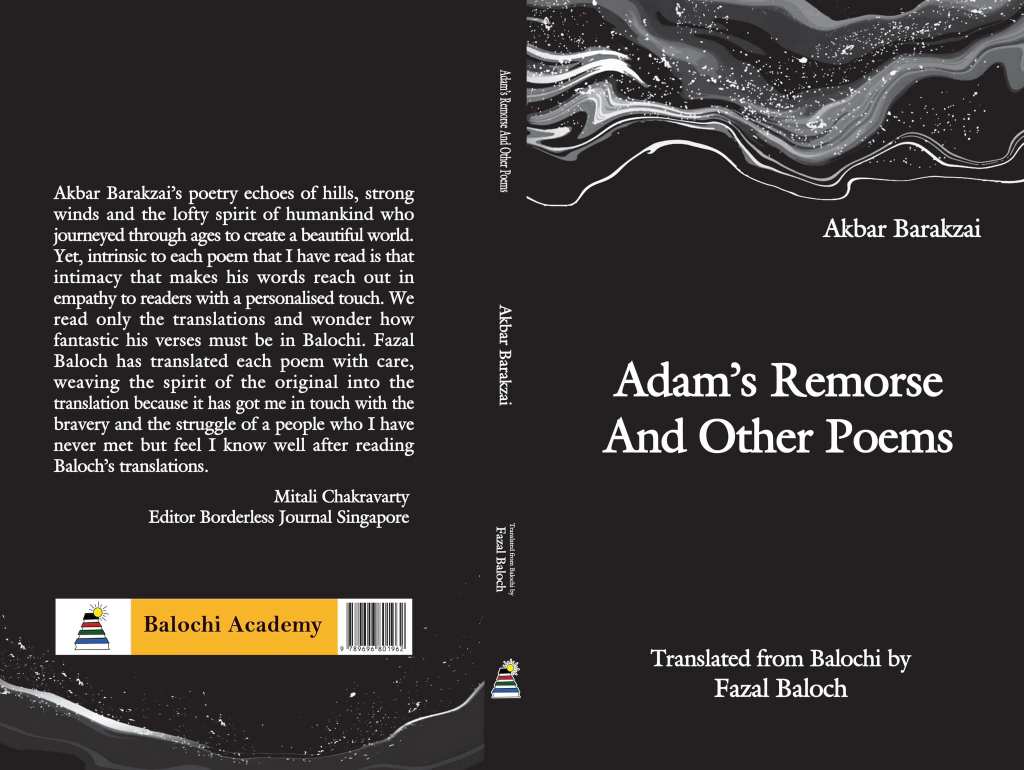

“Akbar Barakzai belongs to the generation of the poets that witnessed the political and literary activism of Muhammad Hussain Unqa, Sher Mohammad Mari, Mir Gul Khan Naseer and Azat Jamaldini”, writes Fazal Baloch, a renowned translator who most recently brought out the anthology of Barakzai’s translated poems under the title Adam’s Remorse and Other Poems, published by Balochi Academy Quetta in 2023.

In his literary career, which spans over a half century, Barakzai has managed to bring out only two of his anthologies. Some selected poems by Barakzai have been translated from Balochi to English by Fazal Baloch, a college professor in Turbat, and a prominent literary translator.

Akbar Barakzai was an honest and dedicated political and social activist whose aim was progress of Baloch people. He as poet could not only express the human sentiments but could also express their aspirations for their life of Freedom and Dignity. “He served … his people admirably and deserves our respect and love,” says Meer Mohammad Ali Talpur, a Baloch intellectual.

Barakzai’s poems are rich in linguistic and literary expressions. His language is both simple and philosophical. In his poetry, he celebrates resistance, challenges oppression, and expresses a belief in a better future without losing hope. He emphasises resilience to overcome suffering. He writes:

I am the tree of immortality,

O, you tyrant brute!

The more you hew me down,

the more I sprout

The imagery of the tree symbolises the strength and the life cycle of a tree which remains steadfast midst harsh weathers.

In another poem, titled ‘Not Forever’, Barakzai continues to convey themes of resistance and defiance. As he says:

The rule of chains and fetters

Will last only for today, not forever.

The age of tyranny and oppression

Will last only for today, not forever.

He inscribes that the current state of being oppressed or controlled (“rule of chains and fetters,” “tyranny and oppression”) is temporary. Barakzai implies hope for a future where such oppression will end, indicating a belief in the eventual triumph of freedom and justice.

Barakzai sought to reshape the prevailing socio-political views and wrote for freedom and liberty, peace and prosperity and dignity of mankind. His love for human dignity transcends all geographical and cultural frontiers and becomes universal, added Fazal Baloch.

Indeed, Barakzai’s poetry transcends borders and speaks to universal themes. In his poem ‘Who Can Snuff Out the Sun?’ written in response to Che Guevara’s execution, he celebrates Che Guevara’s heroism and the universal struggle for justice and freedom. By acknowledging Che Guevara’s courage and sacrifice, Barakzai connects with a broader global struggle for human rights and liberation.

"Who can snuff out the sun?

Who can suppress the light?"

And in the last lines of the poem, he notes,

I'm Ernesto Che Guevara

I'm Immortal

Everywhere in the world

“This is not only Barakzai’s most quoted poem, but it is also one of the most remarkable Balochi poems touching the theme of resistance and defiance,” contends Fazal Baloch.

Similarly, in his another poem like ‘I’m Viet Cong’, he expresses solidarity with the people of Vietnam, few lines are written as such:

I'm the spirit of freedom and liberty

Who can enslave me?

Who can kill me?

After all

I'm Viet Cong I'm Viet Cong.

He might have shown solidarity with Afghanistan in his poem ‘April 1978’. His lines read:

Let's sing for the Saur

Let’s extol the groom

A garden in our heart has bloomed

Doves chant and herald the news

Revolution has arrived

Arrived what we desired

One of the ways in which Barakzai weaves the West and the East into his poetry. He has a poem called ‘Waiting for Godot’. Samuel Beckett’s Godot is emblematic of an ideal that we keep waiting for. Barakzai has captured the essence of the whole play in his poem with his refrain —

Arise! O friends from this deep slumber

Godot will not, will never show up

In one of his most powerful poems, ‘Word’, Barakzai conveys the power of speaking up for one’s rights and the importance of not remaining silent in the face of oppression. He believes that by voicing one’s grievances and advocating for justice, freedom, and salvation can be achieved, ultimately leading to the end of oppression as these lines indicate:

Don’t ever bury the word

In the depth of your chest

Rather express the word

Yes, speak it out.

The word brings forth

Freedom and providence

Of course, freedom and providence.

In ‘How Long’, Barakzai starts by portraying a bleak situation where life is filled with distress and young people are dying tragically. He inscribes,

For how long

Life will remain in utter distress

Handsome youths keep falling to bullets

And mirror like hearts

Continue to shatter into shards?

Then, he shifts the tone to one of hope and optimism, and writes,

Light-- the very essence of freedom

Will not forever remain in prison

Life will not suffer distress

The serpent of tyranny

Will vanish evermore

The sapling of envy and hatred

Will wither away.

He suggests that despite the current darkness, better days are ahead. He expresses confidence that “light”, symbolic of freedom, will not remain imprisoned forever. He predicts an end to the suffering and the disappearance of tyranny. The imagery of the “serpent of tyranny” vanishing and the “sapling of envy and hatred” withering away conveys the idea of a brighter future where oppression and negativity are eradicated.

Barakzai’s poetry is a ray of hope in the midst of suffering from atrocities and hatred and envy. His poetry reflects his love for humanity resonating with the voices of the oppressed and for them.

Hazaran Rahim Dad is a poet and writer. She writes on sociopolitical issues focusing on the right of fishermen. Currently she is pursuing her MPhil degree in English literature from Karachi.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International