By Sohana Manzoor

“Bishti poray tapur tupur, nodaye elo baan”

(The raindrops fall drip drop, the tide rises in the river.)

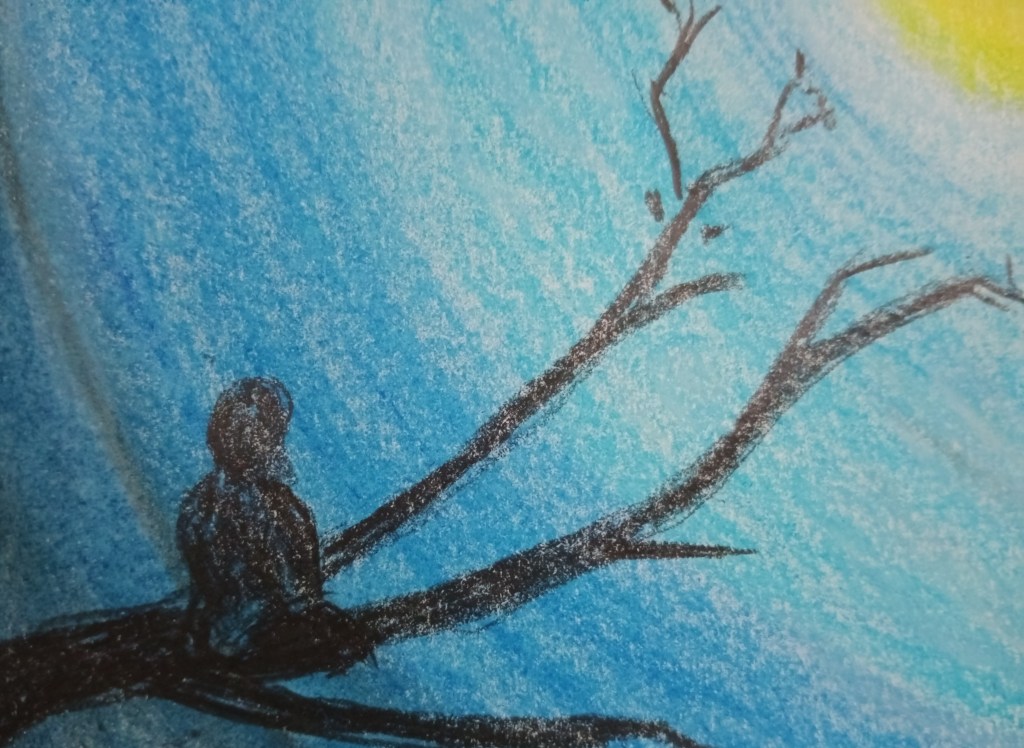

Ratri looked at the small nakshi kantha on the wall. The letters were uneven as if they had been stitched by some unsteady hand. But the bright green leaves and the blue droplets were neatly embroidered. She never remembered it in the last seven years, and yet it had been so much a part of her childhood. She recalled tracing the letters on a small piece of cloth and bringing it to the old lady who was her great grandmother. She had given her a needle with dark red thread and Ratri had made her first embroidery. Her Boro Ma had stitched the leaves and raindrops. The piece had yellowed slightly over the years; Ratri felt numb and stricken.

Why didn’t she remember it all these years? Is it because she always avoided the prospect of coming home? Now the only person who loved her was gone. She looked around the room of her great-grandmother—it still had her smell, faint but it was that intoxicating smell of jarda, incense, and contentment. She noticed her prayer beads hanging by the clothes rack. She took in the peeling green distemper which the old lady preferred to any other colour. The walls of her room were always green. Once it was painted white by mistake and her Boro Ma was furious. “Are they planning to make me blind or something? I need the green to soothe my eyes.” Two days later the walls were repainted.

When Ratri was young, she always felt safe and happy around her great-grandmother. Her mother was a classical dancer with a busy rehearsal schedule and frequent performances. Her parents had separated when she was an infant. Her grandmother had a big family and was busy fussing around the household. Everybody was too busy—only Boro Ma had time for Ratri.

Ratri did not know how her mother smelled—that is, how she really smelled. She saw her from a distance when she was dressed to leave the house or returning from a show. When she entered a room, everyone noticed her, and she wore a tantalizing perfume that Ratri thought was mysterious—just like her. Many years later she recognized the perfume in a famous fashion house in London as Miss Dior. Sometimes she petted Ratri absentmindedly, in the same absent-minded way she petted the house cat Minni. She practiced early in the morning in a room downstairs. She had a beautiful figure and Ratri thought that she danced divinely. Her grandmother often joked that they must have had a baijee in the family tree, and her daughter Nazma had inherited the talent.

Even though she had been married before and had a small child, she had no dearth of suitors. Ratri clearly remembered the bevy of men who came to court her—as one courts a queen, without any expectation of return. They often brought presents for Ratri too. Nazma had a charming smile for everybody, a smile she used to practice before the mirror in her room. She was a consummate artist—everything she did was practiced and trained. Dancing was the only thing she cared about. There were times when Ratri tiptoed to the room where her mother practiced and stood outside the door to listen to the ringing of her anklets and the tak dhin dhin dha – tak dhin dhin dha—na tin tin ta—tete dhin dhin ta that accompanied the music her mother danced to. Some evenings, there were other dancers who joined her, and they danced together. Ratri remembered one night they were all rehearsing a Tagore dance-drama. She thought her mother was some princess or queen and she was ordering her attendants to summon somebody:

“Bol ge nogor paley mor naam kori, Shyama dakitechhe taray.”

(Tell them at the town centre taking my name that Shyama is calling out to you)

Ratri did not understand the words but was enchanted by the rhythm and the spectacle of the performance.

She did not notice Naina Auntie approaching. Her aunt found her entranced by the door and dragged her away. “What are you doing here, Pichchi? You know that your mom doesn’t like to be disturbed during rehearsal. Come with me!” Ratri turned toward her aunt, “She is sooo pretty! Is she a princess?” Naina laughed, “No, she is who she is. A court dancer.”

When Boro Ma heard about the incident, she looked at the child and commented in a stern voice, “Nazu should spend some time with Ratri. She needs to make time for her daughter.” Naina Auntie replied, “She looks so much like her father that Apa does not even want to look at her.”

Boro Ma shook her head. “She should have allowed him to take her then,” she said. “What is the point of keeping her and then neglecting her?”

Neglect.

Ratri had not known then what the word meant. But over the years, she grew up learning all its nuances. She survived because of Boro Ma, the only one person who actually cared. And yet, Ratri would eventually take her for granted, imagining that the old lady would always be there. The years went by so fast—the rainbow years of childhood, the reckless years of youth, and she wondered what she did with them.

*

“Boro Ma!” the little girl came running. The old woman was just done with her midday prayers and had opened her large closet. “Yes, my darling?” she smiled at the upturned face of her great granddaughter.

Usually, Ratri loved to sniff around her Boro Ma when she opened her closet. There were things from the past like her bridal sari that dated from before the Partition, and old embroidered pieces that she had made as a young woman. Curious little sandalwood boxes, and dainty silver trinkets tarnished with age. And there was that mysterious and intimate smell of incense and naphthalene. But today Ratri was too preoccupied to notice.

“Toton Uncle says that I cannot take on a big journey because I am a girl.” Ratri had a frown on her small forehead. “That’s not right, is it?” she asked.

“What do you think?” asked her great-grandmother.

“I think he is wrong. I plan to look for my prince rather than the prince searching for me,” pouted Ratri.

“A ha,” smiled Boro Ma, “so that’s what the journey is about!”

“Yes, but I want to take on the journey. I don’t like that the prince finds the sleeping beauty. Why can’t the princess go in search of the prince herself?” asked a rather peeved Ratri.

Naina, who was poring over a dense medical text, snapped the book shut and laughed out loud. “I guess you do have to look for your prince, Pichchi. No prince will be happy to find you. You are so dark!”

Boro Ma barked, “What kind of talk is that Naina? There are a lot of girls who are dark.”

“But not princesses,” said Naina. “Princesses are pretty and fair, while Ratri is—”

Before she could finish, the old lady intercepted coldly, “Draupadi, the most sought-after woman of ancient India was dark. And Ratri will be no stupid princess, you heard her. She has a mind of her own and will make her own choices when the time comes. Now get out of here before you utter any more nonsense.”

Naina left the room meekly, but Ratri was looking at her arms and legs which were rather dark compared to Naina’s and most of the people in the house. Even her Boro Ma was very fair despite her wrinkled skin.

She looked up at her Boro Ma. “Does dark mean ugly, Boro Ma?” she whispered. She hesitated a little before adding, “Is that why Ammu does not love me?”

“Who told you that your Ammu does not love you?” asked the old lady with a gleam in her eyes.

“Nobody,” replied Ratri. She looked at her feet and examined her toes. She did not want to say that she overheard one of her uncles talking to his wife. She said lamely, “Naina Auntie says that’s why I was named ‘Ratri,’ meaning ‘night.’”

Despite the arthritis in her joints, Boro Ma bent down and grasped the little girl’s face with both of her hands and lifted it toward her. Ratri looked at the liquid grey eyes of her great-grandmother. They were bright and somber.

“Listen, my pet, you are very beautiful. Your skin may not be as fair as your mother’s, but you are lovely just as you are. But even more important is that you are also very brave. You have a beautiful spirit. You want to make a journey of your own—how many little girls want to do that, do you think?” She got up slowly and smiled. “Now, run along and play. Don’t worry over silly things. And don’t listen to Naina.”

Ratri walked out into veranda with her coloring books. It occurred to her that Boro Ma did not actually contradict the notion that her mother did not love her.

*

A week after Ratri’s eighth birthday, her mother married again. She thought her mother had gone on some tour, but Nazma had actually left for her honeymoon, and then to live with her new husband. She had married a business magnate and launched a new life. Nazma had not informed Ratri and had not of course considered taking her to live with her and her new husband.

Ratri’s grandmother thought it odd that the girl did not ask even once about her mother. But Ratri already knew that her life would be different from all her cousins who lived with their parents and siblings. Most of her maternal uncles and aunts had married and moved out by then but visited frequently with their children. Only Toton Uncle and Naina Auntie still lived in the sprawling old British-era house in Lalbagh. Ratri lived there too, along with her grandmother and Boro Ma. She kept mostly to herself, held court in a sun-drenched roof top, and laughed with the birds. She had few friends at school. The only person she could actually share her thoughts with was her Boro Ma. And she did not miss her mother much even though she often wondered why her mother was not like other mothers. But the mysteriously beautiful woman she used to admire from a distance soon became a faded memory.

*

“Ratri, come down. You have a visitor,” yelled Naina from the bottom of the stairs. Their two-storied house was built in the 1920s and large enough to have once housed all six of Ratri’s uncles and aunts.

Ratri did not hear her the first time. She was buried with a pile of books, several guavas and pickles in the attic. The red tabby Minnie with her two kittens dozed nearby. It was afternoon and she was diving under the deep seas with Nautilus and Captain Nemo. She planned to make a painting of the blue ocean and Nemo’s submarine at some point. She was looking for more details when her aunt Naina called to wake her up from her reverie.

Naina yelled again, this time from the first-floor landing. “Ratri! Where are you? You have a visitor, I say!” Ratri thought she must be mistaken. Who on earth would come to visit her? “I’m coming!” she yelled back and dragged herself out of the sea.

She went all the way down to the ground floor. The drawing room, which was usually locked, was now resplendent with the light from a chandelier. Her grandmother and Toton Uncle were talking to somebody. They all turned to look at her and the visitor exclaimed, “Oh, there she is! She does not look like her mother at all.” He sounded surprised but not vexed as people usually were after finding that she did not resemble her gorgeous mother. She never told anybody about her mother, and nobody at school knew that the celebrated classical dancer Nazma Nehreen was Ratri’s mother.

Ratri looked at the stranger. He had a kind face, a slight stoop, and a touch of grey at the temples. She wondered if she had seen him before as his face seemed faintly familiar. He smiled and beckoned her, “Come here, child. Do you not know me?” Ratri made no reply but continued staring at him. She heard a voice behind her, the very familiar voice of her Boro Ma. “How can she know you when you never came to see her once in thirteen years?” She sounded brittle and hostile.

The gentleman stood up. “Nanu, you are still here, I see,” he said with a nervous smile.

“Yes, I am alive and well,” came the answer. Boro Ma entered the room and placed her hand on Ratri’s shoulder. “Why have you come? What do you want?” she asked.

“He has come to see Ratri, of course,” Toton uncle intervened. He smiled and looked at the stranger. “And perhaps take her with him too?”

Ratri was totally confounded. Why would an unknown man come to take her away? Who was he? He wasn’t her mother’s husband, she hoped. She did know that they had a daughter. Nazma came with the child once, a very pretty child in a frilly baby-pink dress. Ratri had seen them from afar and taken refuge in the attic. She wanted no part of their life. Perhaps her Boro Ma had said something stern, and Ratri never saw the child again. Even Nazma rarely visited anymore. She often sent her daughter costly dresses, but Ratri never even tried them on. Did they want her as a baby-sitter? she wondered.

Now she concentrated on this stranger who looked at her earnestly. At length, he said, “I am your father, Ratri.”

At first the words did not make sense to Ratri. Then she suddenly realized that this man was her father, her very own father whom she had never seen, not even in a photograph. A sudden sense of unreality seized her, and she was not sure who she was, or where. She seemed to be somewhere outside her own body.

Boro Ma spoke up, “And where were you all these years, Mahtab? Why are you here now?”

“I—I live in Cyprus,” Mahtab mumbled. “I have a small business there. I only returned to Bangladesh last week. But I came here as soon as I could.”

Ratri’s father seemed to diminish before her Boro Ma’s withering gaze. “I wanted to come before but couldn’t find the time. The business was growing …” He did not finish his sentence but looked at Ratri with an agonized expression. “Nazma made it clear that she did not want me to see Ratri…. But I have finally come. I want to re-establish a relationship with my daughter.”

Ratri could not understand the tight feeling in her chest. She whispered, “Abbu!”

“Yes, yes, I am your Abbu,” Mahtab took off his glasses, his eyes bright and wet with unshed tears. “Ma, you look exactly like my mother.” He held out his arms to Ratri and she found herself ensconced in arms full of love and longing.

They all sat together, and for the first time in her life Ratri felt that she might have a normal life like her cousins and classmates. She may not have her mother, but now she had her father. She suddenly realized why her father’s face seemed so familiar. It was because she looked like him.

Her grandmother cleared her throat and asked, “So, you have come to take Ratri away?”

Mahtab was still misty-eyed, and he said, “I have to figure out how to take her to Cyprus. She will need a passport first.”

Ratri looked at her Boro Ma and said falteringly, “I cannot just leave, right? I live here.”

Her Boro Ma said nothing. But her grandmother and Toton Uncle said in unison, “Come on, he is your father. And you need a proper family.”

When Mahtab left after dinner that night, Ratri felt very strange. Her father! Where was he all these years? And would she really be able to live with him? Like a regular child? She looked up Cyprus in an old atlas that belonged to her late grandfather. She imagined the blue waters of the Mediterranean, and warm sand between her toes.

When it was time for bed, she turned to her Boro Ma and asked, “Boro Ma, what are people like in Cyprus?”

Her Boro Ma did not say anything. After a while she said in a hoarse voice, “I don’t know. Let’s see how things go.” She turned on her side to face the wall and pretended to go to sleep.

*

Mahtab did not come the next day as he promised, but two days later. He seemed disheveled, but Ratri did not notice. She was overjoyed to see him. She sat beside him holding him by the arm and smiling broadly. And then her father said, “Ma, I’m afraid I can’t take you with me. You have to stay here for the time being. Maybe when you grow a little older…” he stopped seeing the ashen face of Ratri.

“Why?” asked Ratri. “Why can’t I go with you now?”

“You are too young,” said Mahtab lamely. “I will take you when you become eighteen.”

“But why?” asked a bewildered Ratri again.

Her father seemed to be on the verge of tears, “I have a family in Cyprus.”

Ratri snapped up to look at her father who seemed to have shrunk in stature. He looked at her imploringly, “Ma, I re-married and I have two sons. Since we don’t have a daughter, I thought Amalie would not object. I told her about you before and that I came to see you. She did not seem to mind then.”

Ratri sat stonily for a few seconds and then slowly disengaged her arms from her father’s. She slowly picked herself up and walked out of the room without looking back. She went straight to the attic.

She heard her great-grandmother on her way out, “That was cruel, Mahtab. Did you have to get her hopes up? Her mother never even looked at her. And you came to tell her of fatherly love, only to abandon her? Shame on both of you.”

Mahtab sat with his head bent.

Ratri never answered any of the letters she received from Cyprus. Even when her mother had cancer and wanted to see her long neglected daughter, she felt no urge to visit her. They were both strangers to her.

She was a rootless tree, she thought. She preferred to remain that way.

*

Ratri made it to the College of Fine Arts thanks to her Boro Ma. She loved that part of town with its tea stalls and flower shops, the imposing façade of the National Museum, and the mystique of the World War II era crater just behind the College itself. It was another world, quite apart from anything else in Dhaka, and even set apart from University of Dhaka’s main campus. By the time she was 17, she was sure that’s where she wanted to study.

Her uncles and aunts thought it was a terrible idea. “What is the point of studying art? Will she become an artist?” Ripon Uncle had asked disdainfully.

“I didn’t ask for your permission,” retorted Ratri.

“Sure,” jeered Maliha Auntie. “Who will pay for it do you think? It’s quite expensive—I hope you know that!”

“And all sorts of weird people go to Art College,” supplied a giggling Naina. “Do you know they often have nude models? And drugs too.”

Ratri felt indignant, but also helpless. “I will pay for her education,” her Boro Ma said quietly.

“You?” Toton Uncle gaped at her.

“Yes, I still have the money Ratri’s great grandfather left me. I also have some property in Faridpur. I will sell it all, if necessary,” she said with determination.

Suddenly, the room went quiet. Nobody missed the old lady’s use of “Ratri’s great grandfather” rather than “your grandfather.” Ratan Uncle, who was the eldest among his siblings and had been listening quietly to all arguments so far, finally said, “I think we all should contribute. She is our niece, after all. We have a duty toward her. Also ask Nazma. She has neglected Ratri too long.”

Ratri wondered why Ratan Uncle suddenly felt responsible. Didn’t they all think of her as an outcast and burden? She felt an immense gratitude toward Boro Ma. She was the one who always stood up for her. Ratri tried to swallow the lump in her throat. She did not cry when people humiliated or hurt her. But love was something she rarely had. And that made her cry.

*

Boro Ma was ill when Ratri got the scholarship to England. She was more than 90-years-old, and her body was starting to betray her. Ratri wondered if she should turn down the scholarship and stay with the old lady. But in her heart, she was already soaring high and wanted to get out of the old house which had become more prison-like than ever. Her uncles and aunts jeered at her artistic talents, her irregular habits and idiosyncratic tastes. Naina Auntie thought she could join a hippie camp. It was the early 2000s, and she wore kurtas and jeans instead of sarees or salwar kameezes, and hardly wore jewelry like other young women her age. She was good looking in her own way, even though she did not have her mother’s exquisite features or complexion. If anything, she tried to distance herself from her mother in every way possible.

Can one grow up and flourish somewhere without feeling any kind of attachment? Boro Ma was her only tie to this house. But even she was not enough to keep her here for the rest of her life. Her life would not really begin until she left, and her great-grandmother seemed aware of the fact.

“Go, my pet,” she said. “This is the chance of a lifetime. Don’t waste it.” She smiled as she added, “We’ll meet again when you return.”

Nobody came to see her off at the airport except their old driver. And Ratri was glad because she was not used to expressing emotion. She felt happy and free. Her palette and paintbrushes were all she needed. She had a new canvas before her, gloriously open to the sky and the horizon, and she would paint to heart’s content.

*

The next four years were the happiest in her life. She met people who took her as she was. There were no expectations except that she excelled in her work. She learned different techniques, experimented with various media, took part in contests and exhibitions, and even won acclaim as a young artist. Mahzabeen Nishat Ratri, the talented young artist from Bangladesh, she thought with pride.

That’s when she met Irfan. They often travelled together and participated in exhibitions jointly. Sometimes they were competitors, but eventually he became her adviser as he was twelve years older than her. She didn’t mind him being older—she felt he was more mature as a result. He had been through a lot in life, just as she had herself. When Irfan proposed, she readily accepted. He had told her about his previous marriage and why it had not worked. “I badly wanted a child. But all Shila wanted was her career,” he said.

Ratri understood. Her mother too only thought of her career. She had heard that even her half-sister, the baby girl she saw with her mother, had had a tough life. Nazma was too much of a careerist to give up anything for children. She sent her daughter to Shanti Niketan at the age of eight.

“O my pet! How are you? When will you come home?” She could hear Boro Ma crowing with joy and longing.

“Did you get my letter, Boro Ma? The one about getting an artist’s residency in France?”

“Of course! I’m so proud of you. But aren’t you coming to see me? I’m getting old,” she sighed.

“I’m planning to.” Ratri paused. “I will bring Irfan with me. We are getting married.”

The phone went quiet on the other end.

“Boro Ma—I told you about Irfan, remember? He is a great guy. You will like him, I promise.”

“He’s too old for you, my pet.” Boro Ma’s voice suddenly sounded like that of a stranger. “And he looks like a catfish. You won’t be happy with him.”

Ratri was dumbfounded. She had always been supportive of Ratri, not hurtful like the others. She tried to reason with the old lady. “Boro Ma, do looks really matter? I am not pretty either. But he is loving and supportive, and he genuinely cares.”

Her Boro Ma was unmoved by Ratri’s remonstrations. She said that she felt in her bones that Irfan was not to be trusted.

The next couple of days Ratri felt lost and depressed. Finally, she decided to tell Irfan about the conversation. Irfan was taken aback, but then he laughed out loud. “I think your Boro Ma is jealous,” he said.

“Boro Ma jealous?” Ratri thought that was the most ridiculous thing she had ever heard. But the more she thought about it, the more it made sense. After all, Boro Ma would no longer be the center of Ratri’s life, and perhaps it was natural for her to feel jealous. Poor Boro Ma!

Ratri felt awful, but proceeded through with the wedding plans, which she felt was her one chance at happiness.

She returned to Dhaka with Irfan and took him to see her relatives. Her uncles and aunts now appreciated her since she was starting to make a name for herself. The Bengal Gallery had invited her to take part in an exhibition later in the year, and she hoped to get a spot at the Alliance Française as well. One of her younger cousins even took her autograph. They all congratulated her—except Boro Ma. She simply looked at her and then turned to face the wall.

Ratri remembered the night after her father’s first visit. She had turned to face the wall at the prospect of Ratri’s departure. For the first time, Ratri wondered about the nature of Boro Ma’s love. Did loving someone mean to possess them, and not let go? She wondered if all love was like that.

*

A couple of days before their wedding, Irfan asked Ratri to take a walk with him and share a plate of fuchka at Shahbag. It was February, and the weather was cool and pleasant.

“I want you to meet someone very special,” he said smiling. On the grassy lawn in front of the College of Fine Arts, he beckoned to a young girl of about twelve. Ratri was sitting under a champak tree wearing a green saree with yellow sunflowers. She did not usually wear a saree, but that day she did.

“My daughter, Laboni,” he said. “She is the light of my life. And Laboni, this is Ratri. She is the lady I told you about.”

Ratri stared at the lanky young child-woman who stared back at her with open hostility. The girl turned to her father. “She is not pretty like you said, Papa,” she said.

Irfan apologized after Laboni had retreated into the Central Public Library that she frequented. Irfan and Ratri were walking from the TSC toward the Kala Bhaban. “She is young and sentimental. I hope you understand.”

It was early spring. Around them, the krishnachura trees blazed their vermilion blossoms, and the shonalu flowers hung like molten gold. They would be imprinted in her soul forever. The sound of her mother’s anklets flitted through her mind. Tak dhin dhin ta, the tablas intoned. The pain of rejection, the elusive happy family.

“Why didn’t you tell me about Laboni?” she asked.

“I was afraid. I thought you would not agree to marry me.”

“So, you deceived me.”

Irfan laughed a little uneasily. “You’ve missed so much love in your life, Ratri! I am sure you will understand her pain.”

“Yes,” Ratri agreed. “I do understand.”

Irfan was relieved. “I knew you would.”

“But you don’t understand either of us, Irfan. That’s the problem.” Ratri took a deep breath.

“What do you mean?” Irfan was taken aback.

“I was in her position once. That girl wants her father. But not her father’s new wife.” Ratri paused. She turned to look at Irfan. “And I want a man to love me wholeheartedly. Without being deceitful.” She took another deep breath and said, “Our marriage is off.”

“No!” Irfan gasped. “The wedding has already been announced, and all my friends and family have been invited. I cannot call it off now.”

“You are not calling it off. I am,” replied Ratri calmly.

“You are insane, Ratri!”

She shrugged. “All the more reason for you not to marry me.”

*

Nine years had passed since then. And she had tried not to remember.

Ratri sat in her old hole in the attic. The night sky was clear, and she could see stars even though tall buildings loomed over their old home. Buildings that had risen while she was away. Towering apartment complexes had replaced many of the old and crumbling homes. But a few remained, including this one.

Ratri had not gone back to live in the old house in Lalbagh after the breakup with Irfan. She taught at the College of Fine Arts and lived in a women’s hostel nearby. She withdrew into herself like a snail. She ate, slept, and worked like an automaton. If people gave her odd looks, she did not notice. When she won a scholarship to France two years later, she broke all her ties with her family.

Only last month she met an elderly lady at one of her exhibitions. “Your work is very moving, you know,” she said. “Oui, très émouvant. It shows your knowledge of the human soul.” Ratri was drawn into the pool of her liquid grey eyes. “You have a beautiful spirit.”

Ratri thanked the woman politely, but her world was crumbling. What knowledge did she have of the human soul or of its depths? “You have a beautiful spirit.” The words echoed from the faded corridors of the past. “Boro Ma!” the child in her cried out. And Ratri could hear her incessant sobs.

“She cried for you a lot during her last days. She kept on asking for you,” said Toton Uncle sadly. “She wanted only you. We did not have any contact information, Ratri. I understand you had no reason to remember us. But how could you forget your Boro Ma?”

Ratri looked at the small nakshi kantha. Boro Ma had asked that they give it to her when she came back. “She said she knew you would return, and she asked us to give it to you.”

Yes, of course, thought Ratri. Boro Ma was the mother she never had. How could she forget her? She whispered into the nakshi kantha, “Boro Ma! I am sorry. I was angry. I was so hurt. I am sorry, Boro Ma.”

She held the small nakshi kantha close to her chest and thought of the days when they did so many things together. Her body shook as spasms of overwhelming grief engulfed her entire being. The raindrops in the nakshi kantha melted before her eyes and finally Ratri cried.

Glossary

Nakshi Kantha: Embroidered quilt

Boro Ma: Great Grandmother

Jarda: Tobacco

Baijee: Professional dancer

Pichchi: Little one

Apa: Elder sister

Ammu: Mother

Nanu: Grandmother

Abbu: Father

Ma : An affectionate way of addressing someone younger, technically, mother.

Fuchka: A savoury snack

Oui, très émouvant : Yes, very moving. French

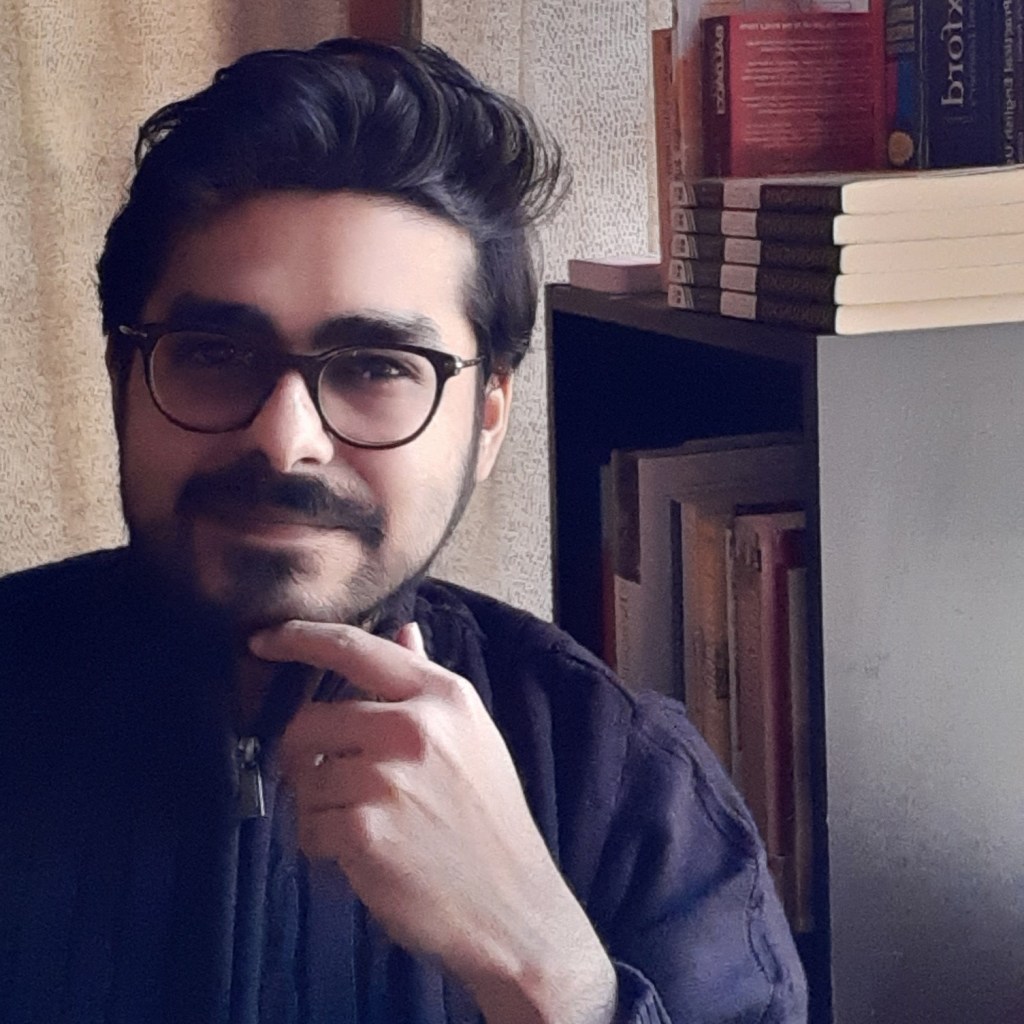

Sohana Manzoor is an Associate Professor at the Department of English & Humanities, ULAB. she is also the Literary Editor of The Daily Star. “Elusive” was first published in an anthology, It’s All Relative, in 2017.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL