By Krishna Sruthi Srivalsan

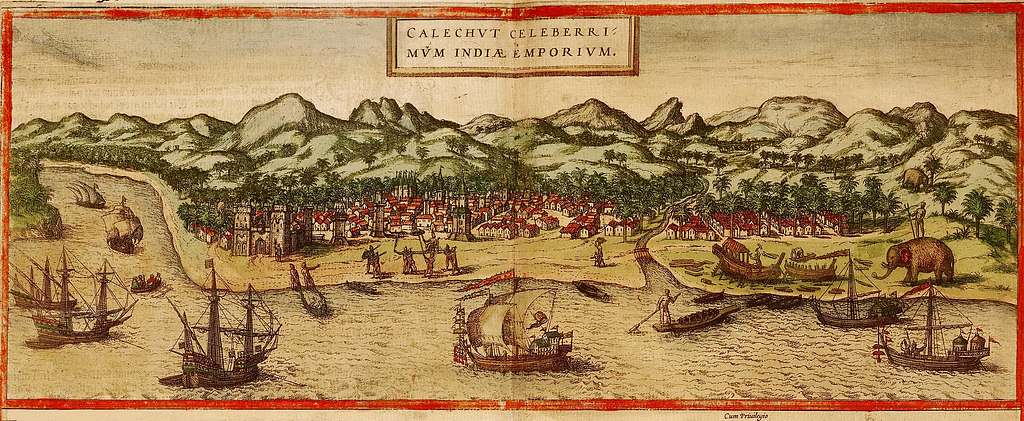

Calicut, 1572

Modern Calicut

The call for fajr from the local mosque Pierces the stillness of early morning, The sruthi box in the puja room stirs awake.

It is dawn in Calicut. The house is quiet, except for the muffled sound of water from the washroom, where my aunt does her ablutions before prayer. She shuffles her way into the puja room and hurriedly shuts the door, careful not to let even a slice of light escape the room and disturb the rest of us. For the next hour, she will be in deep meditation.

Across my bed, I see Amaama. Wisps of white hair framing her toothless mouth, she seems peaceful. Sleep didn’t come to me easy the previous night. A long journey back home and the sudden shock of seeing my grandma succumb to inevitable illness, leaving both her mind and body fragile, have rattled me. I watch her, drifting away in the land of nod.

As the sun peeks out reluctantly from the rain clouds, she wakes up. She looks at me, a question mark on her face. “Do you remember me, Amaama?” I ask. She nods, but when I ask her to tell me my name, she mumbles. I realise that I have become unrecognisable to her. Even after watching her struggle with her memory for the past two years, this upsets me.

My aunt makes idlies for breakfast. I offer to feed Amaama idlies and sugar. It is the food of infants, but it seems like she is a helpless child all over again. After an hour, she quips in a plaintive tone, “I haven’t eaten anything.” We make her a cup of Horlicks and she smacks her lips appreciatively while sipping on the sweetness of the malt.

I spend the day sitting near her bed, reading, in an effort to forget the maze of memories that cloud my mind. I also feel vaguely guilty, though I can’t really tell why. Should I have called her more often when I was away? Should I have been more affectionate to her when she could remember? Could I have been a better grandchild? The regrets pile on, one after the other, and then I understand that the root cause of my guilt is the startling realisation that I never got to know Amaama as a person. All my life, she has been Amaama. What was she like as a child? What was she like as a young woman? What made her happy? Did she have any regrets? I will be in Calicut for the next two weeks and I determine to make use of that time to understand more. I speak to my aunts, pore through old photographs, try talking to Amaama herself.

*

A little girl in pigtails and pinafore Finds the greatest joy In knitting needles and yarn.

My grandmother, Saraswathi Menon, was born in 1932. Her ancestral house is in a village called Kalapatti, in the district of Palakkad, in the foothills of the Western Ghats of southern India. Sarasu, as she is known to her family, was the fifth of seven children. Her father was an inspector in the public works department of the Indian Railways. The family moved between Tuticorin and Sucheendram, two towns on the tip of the Bay of Bengal, and Sarasu grew up in relative affluence. The first brush with hardship must have come at the age of eight, when she lost her mother, who at that time was hardly thirty-three.

Sarasu’s paternal aunt helped raise her, and she moved back to her hometown in Kerala with her younger siblings. As a teenager, she developed a lifelong interest in embroidery and knitting, spending all her time with her knitting needles and balls of yarn. She did not pursue studies after her high school matriculation exams; she did not pass the English examination and did not want to place a burden on the family’s dwindling finances by making another effort.

A memory of Amaama urging me to study flashes across my mind. At that point, she had self-deprecatingly joked that she had no buddhi and that’s why she didn’t study further. I think back and often marvel at how Amaama still aced the many challenges that life presented her, despite this lack of formal higher education. To think of the person she could have become with the right opportunities…

Barely out of her teens, Sarasu returned to Tamil Nadu, as a newly married bride. This time, she found herself in Trichy. I look at Amaama sitting in her bed, propped up by pillows, listening to a version of the Ramayana rendered by Kavalam Sreekumar. I try to jog her memory, and surprisingly, she offers a story of her Trichy days. Her eyes well up as she mentions hopping onto rickety buses that took her to the Rockfort temple and the Sriranganathan temple on an island in river Cauvery. She smiles as she remembers an old lady who taught her how to make murukku and other delectable goodies that she treated her daughters to after a long day at school. She remembers getting married to my Thatha, and accompanying him to the various towns that his job as a sales engineer demanded.

I try to ask more questions, but Sarasu’s spark has disappeared now, and Amaama cannot remember anything else. She can remember events that occurred more than thirty years ago, but she cannot remember what she ate this morning — how treacherous is this mind!

As Kavalam Sreekumar sings in the background, my aunt quietly tells me of Sarasu’s first born child — it was not my aunt, as I had always thought. Sarasu’s first born was a boy; they named him Ravi but they lost him to smallpox at the age of two. This news startles me again — how had Amaama coped with the loss of her only son all those years ago? He would have been the brother my mother never had. How little do we really know of those close to us!

Life blessed Amaama and Thatha with four other children, all of them girls. My aunt talks about the ridicule and pity heaped on her parents, Amaama in particular – “Four girls! No sons! How will you raise four girls?” They raised them with love, making numerous sacrifices, instilling in them courage, confidence, compassion, and a sense of fierce dignity, a determinedness to be independent. It is a testament to Amaama’s sacrifices that all her daughters, and by extension, us — my cousins and I — have reached so far.

*

Coffee stains on the table A jumbled-up algebra problem Anger turns into a ghost of regret.

The day has come to an end. I have learnt new things about Amaama’s life, and I can now see a glimpse of Sarasu, behind the shadow of Amaama. My mother lights the lamp and takes it to the entrance of the house, chanting “Deepam, Deepam!” It is auspicious to keep a lit lamp at the door front at twilight. The air is alive with the buzz of mosquitoes. Amaama is awake. I venture to sing an old bhajan which she used to love. She smiles, she seems to recognise the song, but she still cannot recognise me. Memories spring up from the cobwebs of my mind.

It is supposed to be a holiday for Amaama. Two months in Dubai with her youngest daughter, my mother. I am in grade 10, at the peak of schoolgirl rebellion. A few weeks before the all-important board examinations begin, we have study leave. With my parents away at work, I find myself alone with Amaama.

One morning, I am working on algebra, timing myself to see how quickly I could finish a sum. I hear a cup of coffee being knocked over in the kitchen, but I pretend not to hear. Amaama calls out for me, but I ignore her. When she calls me a third time, I can no longer ignore her, so I stomp into the kitchen, sulking. Not saying a word, I mop up the coffee stains, and slam the microwave to warm another cup of coffee from the flask.

Amaama has not spoken a word about my unreasonable behaviour. I know I have reacted badly, behaving like a spoilt child, but a false sense of pride keeps me from apologising. I hand her a second cup of coffee and try to study for the rest of the day. It is a completely useless day; my anger has now turned to regret and guilt.

When my parents return from work, I observe Amaama speak with them. Will she snitch on me, complain about the brat they raised? She remains quiet, does not say a word about me; instead, she asks them about their day and tells them about gifts she wants to take back from Dubai. I feel uncomfortable. I would have felt better if she had reprimanded me instead.

That night, I toss and turn in bed. Amaama and I share a room, and I hear her sob quietly into her pillow. Guilt engulfs me. I reach out to hug her and I begin to cry too. Amaama turns over and asks what is upsetting me. Exams, I mumble, not wanting to apologise. She hugs me tight and says “What is there to worry? You’re such a midukki kutty. God is always with you!” I sob into the softness of her sari and she says, “I was wondering why my midukki kutty doesn’t like me anymore!” I reply in my garbled Malayalam that I would always love her, but I still did not apologise.

Forgiveness has always been Amaama’s best friend.

*

Barefoot pilgrims walk to Pandharpur Saffron flags fluttering in the wind “Vitthal! Vitthal!” The palkhi bearers chant.

It is pilgrimage season in Maharashtra. Visiting my aunts in Mumbai after ages, we arrange for a trip to Shirdi. A road trip will take us at least six hours. Amaama cannot sit in a car for that long. We decide that the Shirdi trip can wait, but Amaama insists that we do not cancel on account of her. “I’ll stay alone. Will keep myself busy with TV and my books. And anyway, Padma will come for a few hours in the afternoon, so I won’t be lonely”, she says. I wonder what sort of conversation our Marathi speaking helper will have with Amaama whose vocabulary in Hindi (leave alone Marathi) does not extend beyond Kaise Ho! I tell my parents and aunts to go ahead, and I offer to stay with Amaama. “Nothing doing, you have to go see the Baba at Shirdi!” Amaama insists. I slowly understand where my mother gets her stubbornness from.

We set out at dawn the next day and reach Shirdi a little ahead of noon. We spend the next few hours in the temple town, offering our prayers, and soaking in the meditative stillness of the masjid where Baba lived — it is a salve to a weary heart. Before dusk sets, we leave Shirdi. We whizz past fields of sugarcane and cotton, growing in abundance, on the rich black soil of these lands, stopping for a quick cup of tea at Igatpuri. There is a thick shroud of mist, and my mind keeps wandering back to Amaama. What could she be doing, all alone in that flat?

We reach home an hour before midnight. The Matunga neighbourhood is quiet. Amaama is in her chair by the puja room, reading Narayaneeyam. “Did you get scared, Amaama?”, I ask. She shrugs away the question and asks me back, “What is there to get scared of when I have God by my side?” Faith has always been Amaama’s best friend.

*

The Nilambur river quietly chugs along Through hills and fields and forests And merges into nothingness at Beypore.

It has now been three years since Amaama finally succumbed. Watching her struggle through ill health, losing control of her mind and memory, has been an excruciating journey for all of us. Ironically, death seemed to free her, release her from the terrible pain she endured for a few years. When I miss her a little too much, I turn to my phone which had faithfully captured a Boomerang video of her making a dosa when she was in better health. It reminds me of better days in the past when she would make bite sized unniappams, as dainty as the dimples on a toddler’s fist. Sometimes the grief of losing her is too much to bear. I think of a story I read as a child — something about a magic pot which kept cooking porridge for a hungry family. The family gobbled up the porridge, but the pot simply would not stop. It kept cooking porridge, till the porridge overflowed and flooded the entire city! Sometimes, my grief is like that. But then, I look at the photo of Amaama by my bookshelf. A sparkle in her eyes, and a half smile on her lips, she looks the picture of equanimity.

Many dawns have now passed by in that house in Calicut. Sometimes, during the monsoon season, I gaze at the grove of coconut trees outside. The wind rustles the coconut palms and the foliage sways, like dervishes drunk on divine nectar. Sometimes, a bubble of calm quietens an intense battle in my head. Sometimes, instead of holding onto an angry thought, I just let go, like the Nilambur river. In those times, I feel as if Amaama is watching me, from somewhere, where she is reunited with her beloved Krishna, where she can forever listen to the lilting melody from his flute, where she can watch him play by the Yamuna river. In those times, I feel as if her prayers and love have formed a protective shield, an invisible amulet protecting me from all perils. Love has always been Amaama’s best friend.

Glossary

Fajr – The first of five Islamic prayers, also known as the dawn prayer

Sruthi box – An instrument used in Indian classical singing to help tune the voice

Puja room – A shrine room for worship, religious rituals, prayers, and meditation in a Hindu household

Amaama – Malayalam word for grandmother

Idlies – Steamed rice dumplings, traditionally eaten as a breakfast dish in south India

Buddhi – Malayalam word for intelligence

Murukku – Savoury crunchy snack made from rice flour and lentils

Thatha – Tamil word for grandfather

Deeepam, deepam – The word “deepam” means lamp in Malayalam. In Kerala, at dusk, women carry lit lamps to the entrance of the house, chanting “deepam, deepam” in order to invite light and auspiciousness into their homes.

Midukki kutty – Malayalam term for smart girl

Vitthal – Form of the Hindu god Vishnu or Krishna, as he is known in the state of Maharashtra

Palkhi – Marathi word for palanquin. In this context, the verse refers to a yearly pilgrimage where devotees carry the sandals or padukas of the saint Dnyaneshwar from his shrine at Aalandi to the famous Vitthal temple at Pandharpur. The barefoot pilgrims carry the padukas in a wooden palkhi and the journey takes around 21 days by foot.

Shirdi – A town in Maharashtra, which is the home of Shirdi Sai Baba, a revered fakir or saint

Kaise ho! – Hindi phrase for “How are you?”

Narayaneeyam – An epic poem, comprising of 1,035 verses, narrating the life of Lord Krishna. The poem was composed in the 16th century by Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri, a renowned Sanskrit poet hailing from Kerala.

Unniappam – Sweet dumplings made with rice, banana, jaggery and coconut

Krishna Sruthi Srivalsan is a chartered accountant by profession and is passionate about books, writing, travel, and celebrating diversities, not in any particular order. She firmly believes that human beings should not strive to “fit in” when they are designed to “stand out”. She reads on a variety of subjects and genres and hopes to publish a novel someday.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL