Book review by Debraj Mookerjee

Title: India Dissents — 3,000 Years of Difference, Doubt and Argument

Editor: Ashok Vajpeyi

Publisher: Speaking Tiger, 2020

Every man loves liberty and freedom.

Do not interfere with another’s freedom.

– Gautam Buddha

They say inside the heart of a black hole there is a point of singularity. A point of singularity is where no laws of nature exist, like in the instant before the big bang. That point is so powerful that it obliterates all the rules of the universe. It is a place where the laws of nature collapse. We cannot know what happens inside a black hole, because we do not have the tools with which to predict what might be happening inside. There is no physics. Essentially there are no bearings. There is a lesson in the analogy presented here. When power becomes absolute, it freezes everything within its domain. The only way to prevent power from becoming absolute is to check it. Edited, and with an introduction, by poet Ashok Vajpeyi, India Dissents (Revised and updated edition: 2017, 2020) is a critically important book at a time when many believe India might be hurtling towards its own tryst with ‘singularity’. This timely tome is an attempt to articulate the contrarian views inherent in the Indian tradition, spanning from times of yore, to the present. It is an attempt to chart the organic link between freedom and the courage to check power and its manifestations, whether spiritual, social or political.

The most effective way to check power, as demonstrated by this compendium of ‘3,000 years of difference, doubt and argument’, is to call it out. Dissent is at the heart of the human desire for freedom. And without freedom, we are not human. Lord Acton (who’s by and large more quoted than understood) defines liberty thus: “the assurance that every man shall be protected in doing what he believes his duty against the influence of authority and majorities, custom and opinion” (The History of Freedom in Antiquity).

Critical moments in history have seen the suppression of freedoms. The progress of the human race has not been linear. Ancient India experienced great enlightenment in thought and philosophy. Those who have had to endure the attempt – by contemporary media platforms and concomitant experts – at manufacturing consent vis-à-vis a narrow world with narrow identities, via appeals to visceral emotions and spurious theories of hurt and cultural assault, might be surprised to read from the Brihaspati Sutra (foundational text of the Charavak school of Indian philosophy, composed in 600 BCE):

“There is no heaven, no final liberation, not any soul in another world,

Nor do the actions of the four castes, orders or priesthoods produce any real effect.

The Agnihotra, the three Vedas, the ascetic’s three staves, and smearing one’s self with ashes,

Were made by Nature as the livelihood of those destitute of knowledge and manliness …”

The Classical Age saw the birth of Democracy in ancient Greece. Absolute power was kept in check by the voice of the people within the Senate. In India, the counsel of wise voices ensured virtuous actions by Kings. When power heeded the voice of the people or the counsel of the wise, society remained enlightened. But there were intermittent periods of darkness, such as the 1,000 year long dark ages in Europe. The modern world had apparently understood this, which is why modern societies were founded on the principles of liberty, fraternity and equality, the call of the French Revolution against the singularity of power enjoyed under feudalism. But that world is at risk, not only in India but in so many other nations that are otherwise functioning democracies.

Vajpeyi’s book does weigh heavily on recent dissenters whose works are widely in circulation. There is no new ground broken here. And yet it is important for those who have not transcended the plethora of voices that are constantly articulating views smoke-screened by the cacophony of mainstream opinions, championed uncritically by the media, that has long forgotten its mandated role as the Fourth Estate. Some attention is also paid to the freedom struggle, and the thinkers and freedom fighters who left with us a rich legacy of dissent. Amartya Sen traces India’s argumentative nature to our ancient text. He observes how the national penchant for dharnas (strikes) and protests are seared into souls by the struggle against colonial oppression. These voices feature in the book. But the real meat of the book is in the voices of minor poets and dissenting voices (little voices if you like) from our past, unknown perhaps to most.

Here are some voices from the book for you to gauge the diversity of dissent articulated in it. Ghalib in his plaint against God, “Whenever I open my mouth you snap: And who are you? / Is it your culture that I must not speak, only listen to you?” Raja Rammohun Roy against social customs: “Men are in general able to read and write and manage public affairs by which means they easily promulgate such faults women occasionally commit but never consider as criminal the misconduct of men towards women.” And then there is Kazi Nazrul, who along with Tagore, is revered as Bengal’s poetic voice:

“Blow your horn of universal cataclysm!

Let the flag of destruction

Rise amidst the rubbles of prison walls

Of the East!

Who’s the master? Who’s the king?

Who is it that gives punishment

Having snatched away the truth of freedom?”

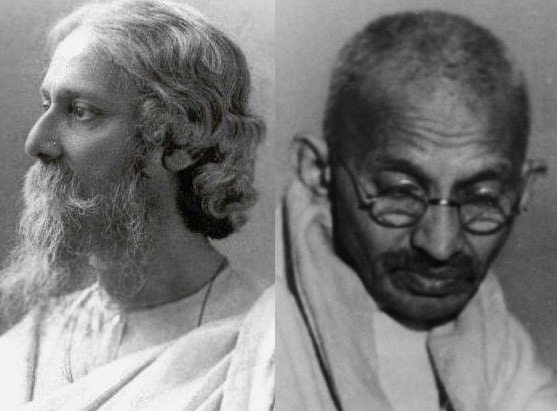

These words of Nazrul would speak to power, were they to be voiced today. Whether it is Gandhi’s articulation of dissent against colonial rule, or Tagore’s denunciation of the idolisation (literally the worship of the nation as Mother, venerated via the slogan: ‘Vande Mataram’) of the nation over humanity, or even Periyar’s cry against superstition and caste oppression, and of course Bhagat Singh’s sharp critique of the world of oppression around him, India Dissents reminds us of what lies at the core of who we are: a plural society shaped by myriad traditions and cultures bearing the influence of peoples from faraway places. No one ruler, no one rule, no one singular identity, can ever define ‘the wonder that is India’ (to misquote A L Basham slightly).

Particularly amusing is the inclusion of the ‘obscenity’ trial against Chugatai and Manto (who was a born dissenter), presented in Chugtai’s voice. The presiding judge being perceptive decided he needed to talk to the contestants in his chambers and had drawn them therein. Chugtai: “The judge called me into the anteroom attached to the court and said quite informally, ‘I’ve read most of your stories. They aren’t obscene. Neither is ‘Lihaf’. But Manto’s writings are littered with filth.’ ‘The world is also littered with filth,’ I said in a feeble voice. ‘Is it necessary to rake it up then?’ ‘If it is raked up it becomes visible and people feel the need to clean it up.’” The judge laughed. Today, no anchor on prime news TV would laugh if told someone needs to rake up what’s wrong with our system so that we could work together to fix it. Such a person would be labelled ‘anti-national’.

India is at the crossroads. Not because its politics is troubled. Politics is all about rotation, and every moment in history is contested by that which is to follow. The world so far has witnessed many ups and downs and so shall India. What is troubling is the anger throbbing inside the people who are ready to rake offense, at almost anything. This is particularly true of the entitled, the middle classes — those with a modicum of education and material wealth. The facile credulity of the great mass of people who can be led by fake news, ‘What’s App University’, misogyny and the willing suspension of disbelief is what is truly threatening I contemporary India. To dissent is to grow. To accent without questioning is to shrink. To read India Dissents is in a way therefore an attempt to try and rediscover India’s soul.

India’s strength lies in its diversity, best explained in the words of Maheswata Devi’s words, reproduced from the book: “Indian culture is a tapestry of many weaves, many threads. The weaving is endless as are the shades of the pattern. Somewhere dark, somewhere light, somewhere saffron, somewhere as green as the fields of new paddy, somewhere flecked with blood, somewhere washed cool by the waters of a Himalayan spring. Somewhere the red of a watermelon slice. Somewhere the blue of an autumn sky in Bengal. Somewhere the purple of a musk deer’s eye. Somewhere the red of a new bride’s sindoor. Somewhere the threads from words in Urdu, somewhere in Bengali, somewhere in Kannada, somewhere in Assamese, yet elsewhere in Marathi. Somewhere the clothes frays. Somewhere the threads tear. But still it holds. Still. It holds.”

Diversity and dissent go hand in hand. To be able to dissent is also to be able to accept the dissent of others. Dissent is not always angry. It is questioning and it is curious. It is at the heart of what it means to be human. It is what makes us modern and free of the prejudices that have often laid civilization low. It is Des Cartes’ great call ‘Cogito Ergo Sum’ (I think therefore I am). The method of doubt foregrounded by the advent of reason, as it were, led not just to political emancipation, but also to the great scientific discoveries that define modern existence. Dissent is the source of discovery and research. Dissent is our door to adulthood, our way of finding ourselves. Any society that demonises dissent shuts the door to what it can become; it shuts the door to as yet unmapped possibilities. By crushing dissent, a society seals its tryst with negativity and slides into the prison-house of its worst fears and anxieties.

But then who is the most distinguished dissenter among them all? My choice is clear: It is none other than Mahatma Gandhi himself. To understand the nature of Gandhi’s dissent, one must first recognise the fact that perhaps along with Emperor Ashoka and the Prophet Muhammad, he was among those who believed in the imperitive of morality in politics, and in the politics of morality. Said he: “In my opinion, non-cooperation with evil is as much a duty as is cooperation with good.” By imbuing a moral quality to political action, Gandhi brought to bear exacting standards to politics, unheard of in the modern era. His very politics dissents against the existing dictum of political action: That politics is the art of the possible.

But Gandhi’s is not merely a great dissenter in politics. He is, in the words of the author of the internationally recognised novel Samskara (1965), and litterateur, UR Ananthamurthy, a ‘critical insider’. Gandhi, avers Ananthamurthy, allowed himself to be absorbed by the traditions of India, and from within that position, articulated his critique of what he saw as wrong with that tradition. He was a devout Hindu who was secular to a fault, and against the evils inherent in Hindu society. It is precisely because of this that Gandhi was so successful in mobilising India both politically and socially.

Alas today, those who are critical are seen as outsiders: westernised, liberal, socialists, and so on. And those who are insiders are not critical: they are viewed as provincial, obsequious, bigoted and belligerent. India will have to find the will to shake itself free of the straight jacket it finds itself in at the moment. That can happen with only more, and not less, dissent.

.

Debraj Mookerjee has taught literature at the University of Delhi for close to thirty years. He claims he never gets bored. Ever. And that is his highest skill in life. No moment for him is not worth the while. He embraces life and allows life to embrace him.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are solely that of the author.