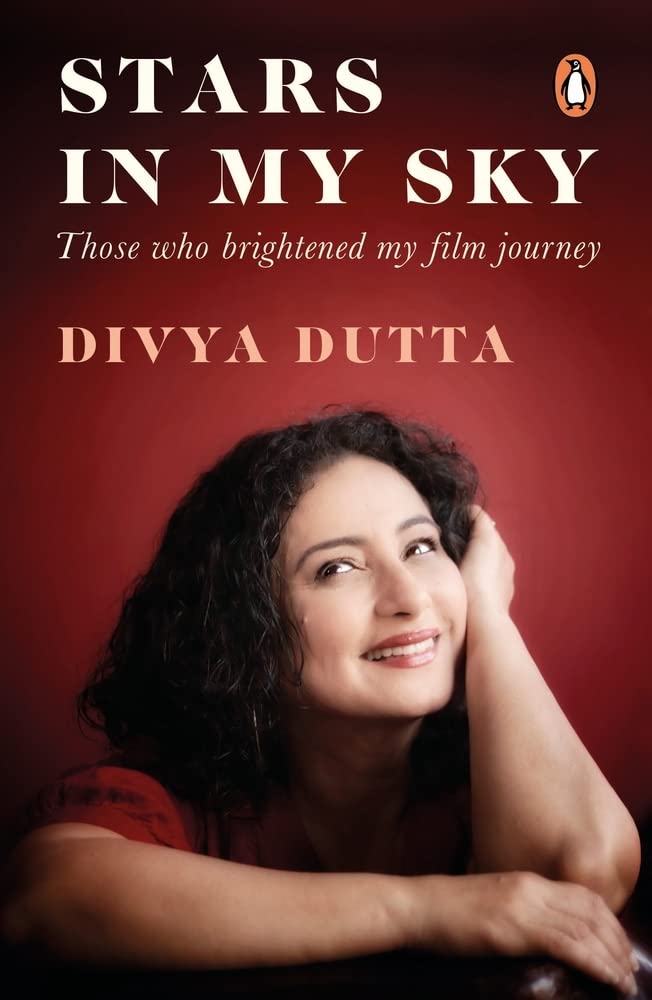

Ratnottama Sengupta, an eminent senior film journalist, converses with Divya Dutta, an award-winning actress, who has authored two books recently, Stars in my Sky and Me and Ma at a litfest in Odisha. Sengupta directs us with her questions to a galaxy littered with Bollywood snippets and emotional stories about life.

Divya you are in this literature festival organised by Shiksa O Anusandhan (SOA)[1], Bhubaneswar with your second book, Stars in My Sky[2]. But your life as an author started with Me and Ma[3]. So your first book was on your personal life. Didn’t your publishers want to know more about your professional life first?

l never had any motive to become an author, you know! My life has been very organic. Things have just happened. Me and Ma wasn’t planned either. My biggest fear was, l didn’t want to lose my mother. Life teaches us that we don’t lose anyone. They may stop living outside of us but they stay on inside us. In our heart. And we have the security that they won’t go away from there. But l wanted to celebrate my parents.

Many a times our dreams don’t match our parents’. Some 25 years back, it was impossible in a doctor’s family to imagine that l would be an actor. There are many parents who force their children to do what they want, they don’t care to understand their children’s dreams or interests. But my mother did.

I would often flip through the pages of Stardust, a magazine which was very popular then. One day an advertisement for a talent hunt caught my eyes. l applied with two amateurish photographs clicked by my brother and never expected to get selected. Much to my surprise, l got selected. So I told my mother, l have to go to Mumbai for an audition.

Both, my brother and I were standing in front of her, our eyes downcast, pin drop silence in the room. My mother said, “You have your second year exams…” And l said, “l promise l will work very hard.” She said, “Look at me.” I looked up. She asked, “Are you sure?” There was a few seconds’ pause. And in those few seconds l realised that this is what l want to do in life.

My mother said, “Okay fine, I am with you.” At that moment happiness filled my heart. And l knew l can never let down this parent because she has believed in me and stood by me, come what may. When she was in the hospital l thought to myself, “Shall l cry or shall l celebrate her?” And l realised l wanted to celebrate her.

So I called Penguin and told them l wanted to write about my mother. They said, “It sounds beautiful, please go ahead. What do you call it?” Till then I had not even thought about what to call it! The title that came out of my heart was Me and Ma because it is the story of a mother and a daughter.

As you said, The Stars in My Sky is commercially attractive but nothing can be more fetching, more precious than your mother. So to me Me and Ma was a bestseller from the outset. I could connect with the readers through the book, through the audio book and now the Hindi version is also out.

Words from the heart!

You see, we don’t build friendship with our parents – neither do our parents. This book is about diminishing those gaps. Children, talk to your parents. And parents, don’t think that you are older, your children should listen to you. Parents too should listen to their children though they may think differently.

I was very fortunate to have outstanding parents. So whenever people told me they had read the book l would call my mother to say, “Mamma l love you.” Many a times we do not say that. We take our parents for granted, and perhaps rightly so — other than our parents, whom can we take for granted? But having said that, I will repeat: We certainly need to convey our love.

The same way parents should convey their love to their children?

Everything in life is mutual but parents, especially a mother’s love is unconditional. Many times when we are in a rush we tell them to “hang up”. Now, when she’s no more, l think, “Whom do l call up when l want her to pick up the phone!”

You touched the core of my heart. When my mother passed away, the first thought that crossed my mind was, “l can never call her again!”

I do call her, and we talk. The bell rings from my heart and we have fun talking, bade majje ki baat hoti hain.[4]

You wrote for your school and college magazines but at which point did you realise that expressing with words rather than emoting is what you want to do? Of course younger years are more about being in front of the camera – later, with your pen dipped in experience, you turn reflective.

All these things are gifts from the universe. When l was writing in my school and college magazines, those were not coming out of experience but were full of sincerity, from my heart. My first love always was to face the camera –- perhaps because l am an ardent fan of Mr Bachchan[5]. I saw him on the screen when l was four or five and was mesmerised. I wanted to belong where he was, which world is it? l wanted to go there.

Remember the song, Khaike paan Banaraswala? [6] I would tear my mother’s dupatta or sari and wrap it around my waist over my kurti. Paan wasn’t allowed, so I would stain my lips with maa’s lipstick. I would invite the neighbourhood kids and tell them that, if they clapped louder after my performance, they would get sweets-and-savoury and rooh afzah [7]too. I loved the claps, the appreciation, the acknowledgment but above all the performance was what l loved most.

As a student too I loved to entertain my class between two periods. I was the head girl but l was the naughtiest in the classroom. My friends would ask me to perform and l performed. So performance is what l always enjoyed. Alongside I wrote. Perhaps I had been experiencing the magic of words.

Emoting beautiful words penned by others is an actor’s job. Beautiful words always touch our hearts. I experienced the magic of words as an actor. When l started writing it wasn’t for a film, it was for me. And it was to find a different world that resonates with me. So, both go parallelly.

Both writing and acting are based on lived experiences. You write about experiences in your life; you also portray a character from your life experience. Let’s hear how your life moulded your characters.

Sure! Let me tell you about Isri Kaur in Bhaag Milkha Bhaag[8].

My mother was a Doctor in a rural area. If the ladies who came for treatment were asked, “How are you?” They would cry. “You are fine?” and they could cry. They’d cry for everything. After school l used to sit in my mother’s clinic and watch everything. I would wonder why these ladies wouldn’t speak but only cry!

Cut to Bhaag Milkha Bhaag. When Rakeysh Omprakash Mehraji cast me he said, “You don’t have much of dialogue. But you must speak through your eyes.”

“No problem,” I replied.

Now let me tell you about the power of costume. I had gone in jeans for a rehearsal of the scene where I’m washing the utensils, but things were not going right, there was a gap somewhere. Then Rakeyshji asked me to wear my costume.

I said, “l’m absolutely comfortable Sir!”

He said, “I insist.”

I changed into a salwar kameez, draped the dupatta behind my ears and then wrapped it around myself — and magic happened. I was washing as if l were a pro! The Director later told me l’d put my hand on burning coal and got burnt, but l don’t have any recollection of that.

Suddenly, l recognised Isri Kaur! She could be the lady who’d come to see my mother. She was there in my subconscious, and tears just trickled down my eyes.

At the end of the scene, l was hugging Milkha. Rakeyshji said, “Give it your end.” So l thought to myself, “Should the end be so clichéd! Brother and sister hug each other, and that’s it?!” All of a sudden l realised that the roles we play, the characters, also have subconscious memories. I remembered Isri Kaur had, as a child, seen Milkha saluting his father, “so do it!” I don’t know where the voice came from but it did. I left that embrace and saluted him just like he did. The entire set fell silent. Every person in the team was crying and that became a cherished moment. This is the power of the subconscious!

Now my eyes are moist! But just as ocean gives back what it takes, so does the ocean that’s life.

Beautiful. So aptly said!

Divya you have two books to your credit. Me and Ma is so personal, and The Stars in My Sky probes your connection with the outer world. What was the difference in writing these two books?

There’s a big difference between writing and acting. Each has a different feel altogether. In acting you part with yourself and allow the character to come in.

You internalise an outsider.

You have put it beautifully. Yes, writing is extremely personal — as personal as my experience with my mother. But Stars in My Sky is my experience with the people l have encountered on the sets. People l shared my movie journey with: Amitabh Bachchan, Shabana Azmi, Irrfan Khan, Javed Akhtar, Gulzar, Shahrukh, Salman…

In the course of making a movie we meet so many people. We cannot say, ‘This person has given me this character,’ or ‘this person has made me a star’. But each of them did something beautiful which l will always remember. Something that brought a smile to my face at that moment. So l thought, l should write about those moments — and you cannot capture those without being personal.

And when you write something on a director or a writer you need to share it with them. These were my personalised accounts. But I’ve had the most overwhelming experience sharing the chapters with them. I saw actors and directors alike cry on reading their chapters. One person l was sharing with over the phone fell silent. He did not speak, nor did I. And l realised that, many a times we don’t say, ‘l like this thing of yours’ or ‘what you did for me made a big difference in my life, thank you.’ So this silence was most rewarding.

It’s so very important to let people know they’ve made such an impact! Now, since we are in a lit fest – which is a celebration of words – l’d like to ask you: what is the thrill in holding a printed book in your hands? Let me elaborate: Today so many things are online. We type or key-in more than we write with pen on paper. Yet I always want to touch the book. After retiring from The Times of India, much of my writing got published online. Some of these got published as an anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles[9]. I was thrilled to hold a copy of that book. Why?

l can certainly tell you about scripts. These days many directors and producers say, “Shall l mail you the script?” I tell them, “Please send me a bound script.” It imparts a sense of belonging, like the power of hugging. When we hug our book, we can feel the power of touch. So I hug my script, my copy, with my name written over it… It’s fun turning the pages rather than scrolling with your finger. The smell of paper, the sound of flipping the pages, maybe reading while eating had left a spot of turmeric… All these give me the feeling, it’s mine. The touch, the smell, of a new book will always remain my first love.

You just said you’ll write stories. Will you also write scripts, and direct them?

I’m in love with acting. And, people who write good screenplays should do that. At the same time, we should be open to life. I never knew l would be an actor, I never knew l would be an author, l don’t know what l will be in future. So l say ‘Yes!’ to what life offers us.

Right – Life is a journey, not a destination.

I will go back a little bit to Stars in My Sky. You have mentioned and we also know that Rakeysh Omprakaash Mehra, Yash Chopra, Shyam Benegal, Shabana Azmi who has written the Foreword, are important parts of your career. Can we peep into that world?

I have been fortunate to work with some brilliant and legendary directors. Let me tell you some stories.

Shyam Benegal is one of the most approachable and humble directors ever. When l came to Mumbai from Punjab, no one said ‘No’ in this industry. Who knows when you will require whom? So when l visited production houses they all said, Yes, they will work with me. And i believed them all. And l called Ma to say l was doing 22 films. Of these, 20 never happened and two were made with other heroines, not me. So I was heartbroken.

During that time l met Shyam Benegal at the premier of Train to Pakistan. I said, “Sir l want to meet you.” He said, “Okay. This is my number, call me.” By then I had become cynical, I thought, ‘Is it that simple?’ But I went to Shyam ji’s office – and he was truly honest. “My film’s casting is done,” he said, “but there is one sequence of folk dance. Will you do that?” I said, “Of course Sir.” The film was Samar. He said, “l will need seven days.” Seven days? Then l will have to learn dance and a lot of things, I thought.

On the very first day he asked me, “What’s your hobby?” I said, “Cooking Sir, l love cooking.” “Okay,” he said, “go to the kitchen, with your co-stars, and make something you like.” I was surprised – when will the dance rehearsal start? But l went to the kitchen, there were Seema Biswas, Rajat Kapoor and others. I used to call Seema Biswas Ma’am. In the process of cooking the formality gave way to familiarity and warmth. Suddenly I found myself saying, “Didi pass me the salt, the paratha is getting burnt!” So Ma’am turned to Didi — and that translated into my chemistry with them in front of the camera. Unassumingly it moulds you into the character, without you being aware of it!

Then he told me, “Go to the folk dancers and watch them dancing.” I went, I saw them dancing, and came back. “Now listen to the song,” he told me. I listened, and responded, “The song is beautiful Sir!” “So choreograph it,” he said. “Me Sir!” I squeaked. Here was Shyam Benegal, who could get any choreographer to do it, but he asked me, all of 18, to do that. Was I nervous! I couldn’t sleep that whole night. But more than nervousness or excitement was the feeling of responsibility: none other than Mr Benegal had asked me to choreograph the song. And when I did it, he asked me to teach it to the dancers. The next day went by in teaching them their dance only!

What a wonderful way to groom a talent!

The day after was the shoot. A night shoot. The entire crew, cast and the villagers were there to cheer me up. There was a 7-camera setup shooting the dance at one go but l was looking at one person alone – Mr Benegal: he was telling me, “Do it, do it.”

I did it to loud cheer. l was scooped up by my co-stars. I felt so beautiful, and so confident. With gratitude l turned around to thank Shyam Babu, but he had left for the next shot! Nothing mattered to him, but he had left behind a girl who had learnt how to take responsibility. A girl who now knew she had it inside her.

Fabulous! This is what make them icons!

Divya Dutta (born 25 September 1977) is an Indian actress and model. She has appeared in Hindi and Punjabi cinema, in addition to Malayalam and English-language films. She has received many awards including a National Film Award, a Filmfare OTT Award and 2 IIFA Awards.

Highlights in Acting:

1) *Shaheed-e-Mohabbat Buta Singh*/ Punjabi/ 1999

2) *Welcome to Sajjanpur*/ 2008/ Director: Shyam Benegal

3) *Delhi-6*/ 2009/Director: Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra

4) *Stanley Ka Dabba*/ 2011/ Director: Amole Gupte

5) *Bhaag Milkha Bhaag*/2013/ Director: Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra

6)*Irada*/ 2017/ Director: Aparnaa Singh

*Divya Dutta got National Film Award for Best Supporting Actress in Irada*

-- (Compiled by Ratnottama Sengupta)

[1] Studies and Research (translation from Hindi). SOA is a deemed University in Bhuwaneswar.

[2] Stars in My Sky: Those Who Brightened My Film Journey (2022)

[3] Me and Ma (2017)

[4] We really have fun.

[5] Legnedary actor Amitabh Bachchan

[6] Literal translation, ‘Eating a paan (betel leaaf) from Benares’, song from Bollywood blockbuster, Don (1978)

[7] A rose flavoured drink

[8] Run, Milkha, Run, 2013, Hindi film

[9] Monalisa No Longer Smiles: An Anthology of Writings from across the World (2022), Om Books International

.

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and write books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself been the recepient of a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International