Ratnottama Sengupta time travels fifty years back as famed actress Jaya Bachchan recounts her first day on the sets of Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar

When Shanti Di, my eldest aunt’s eldest daughter, had got married in 1964, she was already working. So she did not have to face the resistance Arati, the pivotal character of Mahanagar had to face from her in-laws and son. But prejudices and cryptic comments she did face — from her male colleagues. “Women in workplace? They only deprive deserving men of a livelihood,” they would say. “Because, men have to run entire households on their earnings while women work only for the ‘sauce’ — jewellery and saris!”

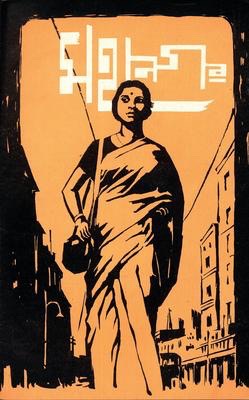

I remembered this at the screening of a restored print of Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963) at Nandan, the West Bengal Film Centre, to mark the 102nd birth anniversary of Satyajit Ray. Based on Narendra Mitra[1]‘s novel, Abataranika (Staircase), the film followed the trials and triumph of Arati, a housewife who steps out of the narrow domestic walls when she finds her husband Subrato bending under the weight of fending for a superannuated father, an aged mother, a school going sister, and their little boy along with themselves.

But once she starts working, she enjoys her new role of conversing with and convincing women with deep pockets to buy her products — and soon her confidence in her work grows along with her empathy with other women who are yet to be empowered like her sister-in-law, Bani, her mother-in-law, Sarojini, her Anglo Indian colleague, Edith Simmons… When her husband loses his job, Arati firmly negotiates a raise. And when Edith is fired for absence due to ill health she takes up cudgel for the ‘insult’.

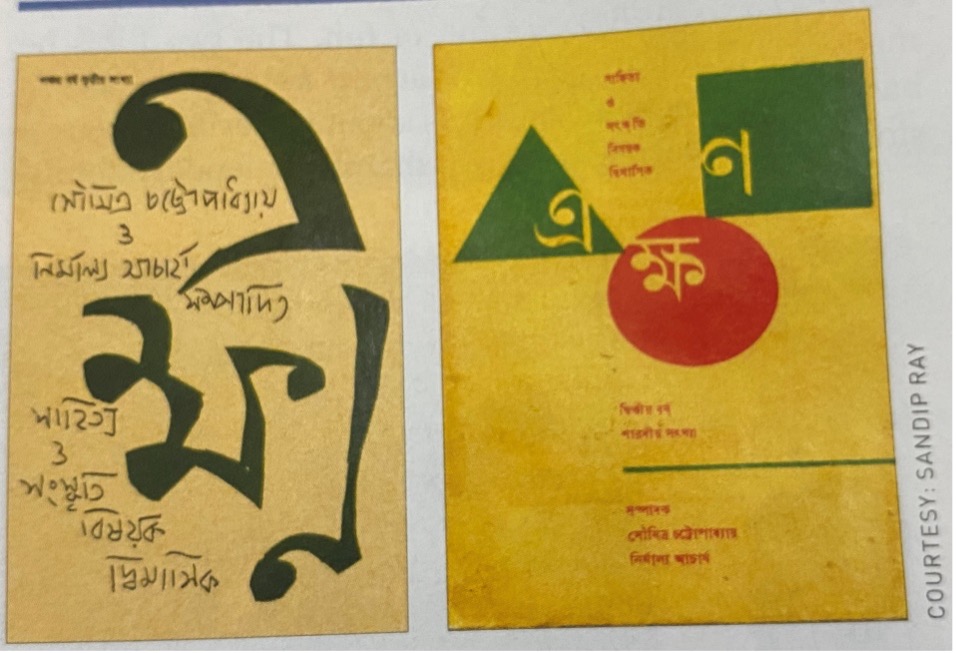

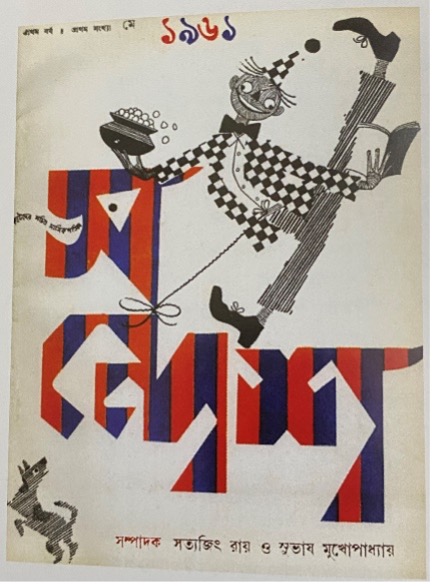

The remarkable sensitivity and the eye for details with which Satyajit Ray etched the ordinary lives of a middle class family earned him the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival 1964. The director’s son, Sandip Ray, remembers attending the ceremony with his parents. “Why were you not there?” a voice from the audience asked Jaya Bachchan, who was in conversation with the maestro’s son, now a renowned director in his own right. “Why would they invite me, who was just a ‘cameo artiste’ as someone mentioned this evening?”

Jaya Di[2] — as I am privileged to address her, much like Sandip ‘Babu’ Ray — was much more than a cameo artiste in Mahanagar. Her ‘Bani’ was a flesh and blood character as she brought to life a marriageable sister who, in my childhood and not just in Bengal, was a part and parcel of any Indian household. Bubbly, sincere, attached to her Boudi as much as to her little nephew whom she mothers when the housewife is earning the family its bread, she is pampered by her brother even as she is being trained by her mother to pick up the haata-khunti…spatula-spoon…in the kitchen!

“I distinctly remember the first day of shooting in Indrapuri Studios. It marked my debut in films. Madhabi Di and Anil Kaku were in that shot which is reproduced whenever something is written about Mahanagar. I am at the study table, trying to write something. Those days I used to wear specs when I was reading. Manik[3] Kaku must have made a mental note of that, he said, ‘Don’t take off your specs, keep them on for the shot.’ I didn’t have any dialogue for the scene. So, although I had not even been on stage before this, I didn’t feel that I was acting. The camera in front of me with Subrata Mitra behind it was not daunting. I was comfortable, just my usual self…”

Little did Jaya Bhaduri know, then, that this ‘girl-next-door’ identity would become her calling card in the years to come, storming even the glamorous boulevards of tinsel town Bollywood.

*

How did Jaya reach the sets of Mahanagar? She didn’t: Ray had sent for the girl in her teens. In all probability, she was recommended by Robi Ghosh and Sharmila Tagore. “They were shooting for Tapan Sinha’s Nirjan Saikatey (1963) when I had gone to Puri with my father, Tarun Bhaduri,” Jaya Di recounts. “We met them and on their return to Kolkata both Robi Kaku[4] and Rinku[5] Di told Manik Kaku that ‘the girl for that role (of sister) has been found at last!'”

The first time she met Ray he did not ask her anything special. Nor did he ask her to do anything particular on the set. Young Jaya was told to read her lessons aloud, which she did, just as any school going child in Bengal did half a century ago. “I remember that Baba told Jaya Di to continue reading after the camera had moved on because he wanted an audio track of her reading in the background,” Sandip recalled in the course of the conversation. “She continued to read, but suddenly there was a sound of coughing. What happened?? In reply to everyone’s anxious query she coolly replied, ‘Why? Can’t a fly wing its way into my mouth while I’m reading?'”

Jaya Di herself has no recollection of this prank, but she vividly remembers that she would pester people on the set, incessantly asking questions. She especially questioned Subrato Mitra for taking time to light up! “It was as if we were out on a picnic,” she smiles. “The entire unit indulged me like a little girl. I was very comfortable because I had no burden to carry. In the presence of major actors I was required to do very little!”

*

Jaya Bhaduri was not given any express direction — neither about how to speak her lines nor about action or emotion. She had full freedom to interpret the scene and react to the other characters. “Manik Kaku used to call all the artistes and read out all the dialogues to us. His intonation would give us an idea of what he wanted from us. We interpreted the scene according to our capacity and gave our best shot. He went about canning it, he never had any problem with my delivery.”

But lessons in acting she did learn on the sets of Mahanagar — by observing how the director groomed the lead actress. “I have seen Manik Kaku directing Madhabi Di to grow into the role of Arati. He literally groomed her in acting. ‘Look this way, through the corner of your eyes. Turn your head like this. Say it like this. Wear the sari in this manner…’ The fact is that Satyajit Ray had a strong visual sense. He envisaged how the character would look and behave at the outset, how she would change, how she would resolve her dilemmas.”

In other words, his actors were not puppets: he allowed the spontaneity of some, like Jaya; he moulded the emotive action of some, like Madhabi Mukherjee who would soon storm the silver screen as Charulata (1964).

*

“Mahanagar was a very modern film, and not just at the time it was made,” Jaya Bachchan observes. Her critique of Ray’s first urban development film gains greater weight from the fact that, in the intervening years, she has ‘grown up’. From a school girl to a trained actor. From the heartthrob of every Indian family in 1970s to the heartthrob of her ‘Lambuji[6]‘ — Amitabh Bachchan — whose charisma straddles two centuries, three generations, five continents. From a reclusive personal life to a vibrant political presence in the upper house of India’s Parliament.

So let me elaborate on her observation, taking off from a scene between her and Subroto, her elder brother in Mahanagar, enacted by Anil Chatterjee.

Subrato has come home from work and his sister asks him for his pen as hers has run out of ink. He enquires when her exams are to commence, then he comments, “What use is this reading and writing? Sei toh henshel thelte hobey, you’ll end up dealing with only pots and pans!”

“Sekhaay toh,” Bani is quick to revert. “They teach us that too – it’s Domestic Science.”

That statement portrayed Ray’s attitude towards housewife. It was and still is a commentary on the identity — role — of a contemporary wife. It is in fact every woman’s attitude in contemporary India,

Jaya Di has observed: “Today every woman also has to and does work. Not only for economic reasons but for identity, purpose in life. Those who have had higher education, certainly do. Those who have not studied much, who help with housework also have such dignity. I see their confidence in the way they carry themselves. They know their mind and they don’t hesitate to say up front what work they will do and what they won’t; how much time they will apportion to a household and when they will leave. And like urban working women, they too save a little from their earnings, use some of it and keep some for emergencies.”

*

Ray’s masterstroke is seen in the way he sketched the nuances of the bank clerk husband, complete with his angst and jealousy. He is proud of his wife’s charming appearance, he is confident she can steer herself through the career of a salesgirl, he is happy when the second income flows in. Yet — and especially when he loses his job — he suffers from insecurity, jealousy, suspicion. To the extent that the man who wrote her application letters, goads her to write a resignation letter. He is redeemed by the stand he takes at the very end when she gives up her much-needed job to protest a wrong against a colleague.

Critics have found Ray to be more kind to the protagonist than Narendra Nath Mitra, the Bengali author who also penned Ras[7] (made into the Hindi film Saudagar (Trader, 1973) which again builds upon how economic realities can make or mar a marriage. About a decade later Jaya Bachchan co-starred with husband Amitabh Bachchan in Abhimaan[8] (1973). In it Hrishikesh Mukherjee takes to an extreme the consequences of a husband’s ego trip when his wife fares better than him, professionally and financially.

*

Earlier Hrishikesh Mukherjee had, in Guddi (1971), given the young sister of Mahanagar a full canvas to come into her own as an actor. The same bubbly girl matures into a woman who can differentiate between love and infatuation. “After Mahanagar I was very selective. I chose to work only with directors who had a ‘Bengali’ sensibility,” Jaya Di says without a hint of hesitation.

And the rapport she struck with Ray? It lasted a lifetime. When she joined the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) she asked her Manik Kaku for a letter of commendation to go with her biodata. He wrote back saying that she doesn’t need an institute but join it, “it is the place for you”.

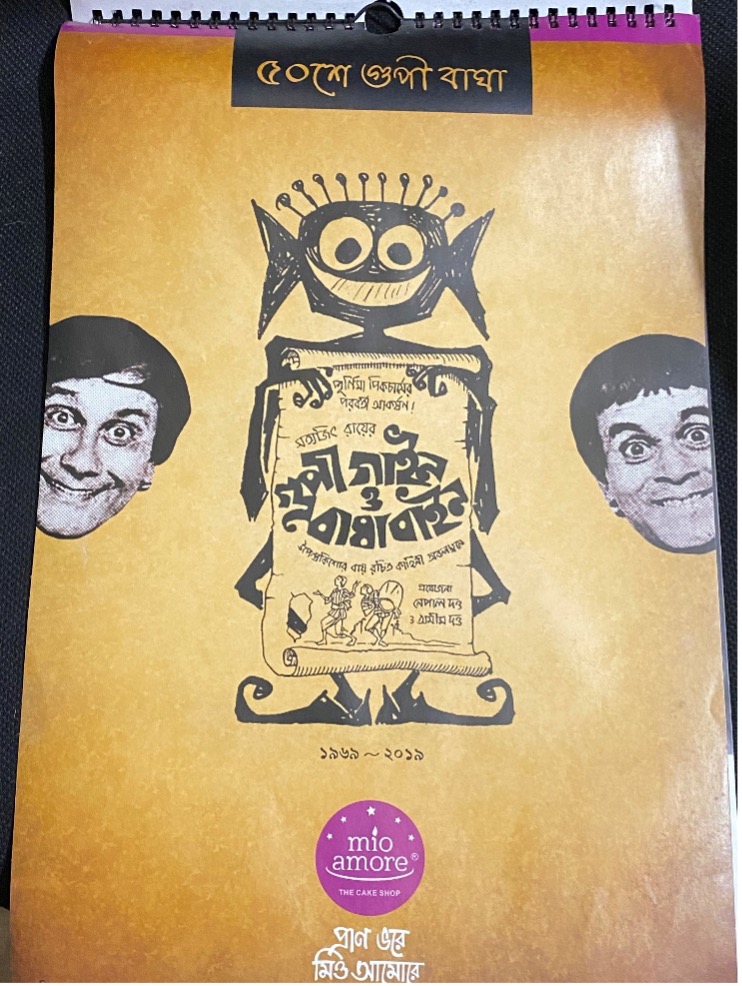

She went thinking she would not last beyond a few months but with batchmates like Anil Dhawan, her co-star in Piya Ka Ghar (1972), and Danny Denzongpa, she stayed the full course. “And when Manik Kaku came with the print of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969), I felt so proud! I went to the airport to pick him up!”

That bonding would show every time they were in each other’s vicinity, Sandip Ray reiterates. “Once we were in Bombay and Baba stepped out of the Taj Mahal Hotel to leaf through books in the stall just outside. Suddenly a shrill voice screamed, ‘Manik Kakuuu!’ Jaya Di was passing by in her car and had spotted him!” “And I hugged him!” Jaya Di adds, “I took liberties others would hesitate to.”

So why was she was not seen in his films again? “There were talks of casting me in Pratidwandi (1970) opposite Dhritiman Chatterjee,” Jaya recalls, “but I was in FTII then. Later I accosted him for not giving me a thought (for the role) – ‘You could have at least called me!’ His reply? ‘It was not necessary.’ That’s all!

“As if to add insult to injury, Manik Kaku got Amitji to do the voice over for Shatranj Ke Khilari (The Chess Players, 1977) but a role for me? No! I was so angry I went and met him in Rajkamal Studio. His reply? ‘ Ha ha ha…’ Not a word more.”

That did not stop Jaya Bachchan from going to Bishop Lefroy Road every time she happened to be in Kolkata. She had, after all, seen the films the ‘Towering Inferno’ made even before Mahanagar. “Every time I watched a film by Ray I felt this is his best. Until the next one came along…” So, when Charulata came, Mahanagar paled. But wait, to this day Debi (The Goddess, 1960) continues to haunt Jaya Bachchan.

And to think that, when Ray had sent for her, the young girl growing up in Bhopal was beset with doubt and hesitation. “I was studying in a convent school, and I feared that the nuns would disapprove of my acting in a film. But my father said, ‘It’s the opportunity of a lifetime — don’t let go of it.'”

Cut to the convent when she went back after Mahanagar. The same austere nuns came and said, ” ‘You have acted in a Satyajit Ray film?! You are so lucky!!’ That is when I first realised, even before he was crowned in Berlin, what a major director my Manik Kaku was!”

[1] Bengali writer (1916-1975)

[2] An honorific for elder sister

[3] Satyajit Ray was Manik to his friends.

[4] Uncle, father’s younger brother

[5] Sharmila Tagore

[6] Tall man

[7] Juice

[8] Pride

.

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and write books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International