Book Review by Meenakshi Malhotra

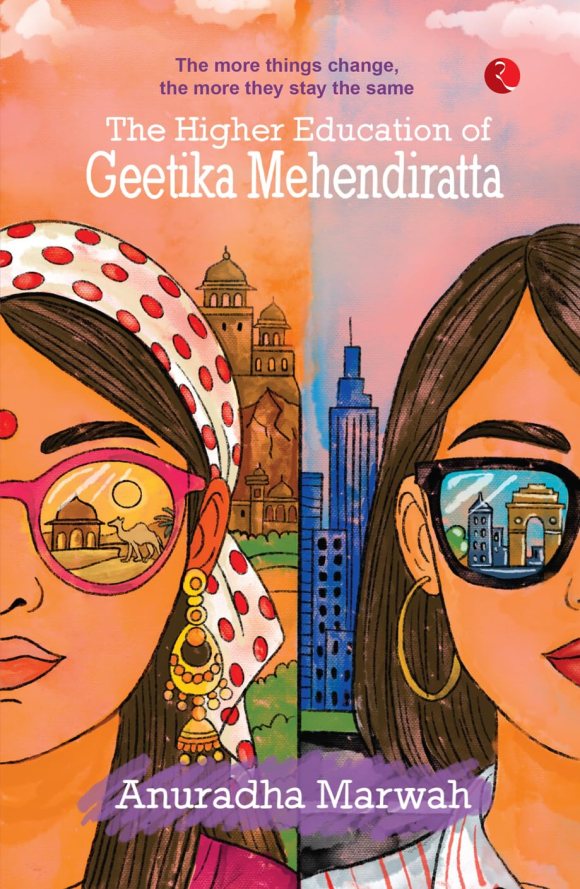

Title: The Higher Education of Geetika Mehendiratta

Author: Anuradha Marwah

Publisher: Rupa Publications

Anuradha Marwah’s debut novel, The Higher Education of Geetika Mehendiratta, republished by more than thirty years after its original publication, is a delightful read. It is a trailblazer and a pioneer in more ways than one-an Indian campus novel before the campus novel became identified as a genre; and a frank exploration of female sexuality without the usual humbug and euphemisms associated with the treatment of sex in many 20th century novels.

It scores in other respects as well-its recreation of small-town ennui before the internet took over our lives, in the middle of a hot summer is a feeling we recognise well. Time moved slowly, people still read books and families still conversed with each other, albeit in the most cliched terms. However, the novel’s tone is not nostalgic, and does not “invite readers into a sepia-tinted past.” (Authors Note)

When the novel opens, we see Geetika whose outlook and family context is quite at variance with the majority of people around her. We cannot imagine her settling into middle-class bourgeois domesticity with her ‘boyfriend’ or otherwise. The slow pace of life and limited options available in Desertwadi make it a claustrophobic trap for someone like Geetika, who is ready to embark on her adventures, both intellectual and sexual. Her experiments in both directions is a sort of liminal phase before she embarks upon the next stage of her life.

The author has hit the right mixture of irony, tongue-in-cheek humour and social satire. Her social satire pierces particularly deep, albeit at the risk of occasionally falling back on stereotypes. This is strongest in the case of the typical small-town aunty, Andy’s mother. Andy, her son, who is attempting to court Geetika, can barely get anything said (or done!) without his mother butting into the conversation or walking into his room. Dalpat Singh is another such character, a corrupt small town sports official who has considerable clout and fully exploits his position in whatever way possible. Geetika realises that “Dalpatji was a reality I could not accept. He did not care if the Indian team won or lost; he only cared about the requisite number of scotch bottles that had to be presented to a journalist in order to get good coverage in the papers.”

Drawing on an undertow of real events like the mega sports hosted by India, ASIAD in 1982, the novel stays moored to recognisable places and times. Sometimes, it almost seems like a ‘roman a clef,’ a novel where real events and people appear with fictitious and invented names. The author has explored the nooks and crannies of the two cities, Delhi (Lutyenabad) and Ajmer (Desertwadi) in intimate detail, the claustrophobia of small town existence and the fraught ‘freedoms’ of the big city which breeds its own threats and insecurities. Double standards of morality and the double binds of gender are both in evidence in the novel. Geeti’s friend, Vinita, gets married to a NRI who while being sexually experienced himself, wants a ‘pure’ Indian wife. Vinita is comfortable with her new husband’s sexual exploits before marriage: she did not mind as it was “all before marriage and men will be men-if girls were game, one couldn’t expect them to be saints.” The double bind of gender is evident in Geetika’s careworn mother. A working woman who is also engaged in social work, Geetika also observes how she has to do the heavy lifting when the domestic help is on leave.

Many aspects this coming of age story seems particularly prescient for a novel that was first published in 1993. Its primary concerns — the stifling and limited choices of life particularly for girls in small-town India, its frank and unabashed exploration of sexuality, narrated in a sassy and unapologetic way make it seem like a fitting story of twenty-first century India. The book accurately captures the inner conflicts of a young woman caught between a society where even progressive parents are limited by the paucity of available options and the narrowness of societal expectations. Geetika inhabits a society that veers between conservatism and a kind of progressive hypocrisy. On a quest to expand the contours of her world, she learns that there are no easy choices and the seemingly viable options of settling into bourgeois domesticity, albeit self-chosen, would clip her wings and disable her from self-realisation. This realisation hits her when she is already into the relationship. Some of the fault lines in the relationship between Geetika and her boyfriend, Ratish, are evident from the beginning. From his conservative perspective, feminism is a problematic term. On being asked about his mother, he declares that she is not a hysterical feminist. For him, a woman’s primary duty is to make herself available and agreeable and be a good mother and wife, and any other aspiration is dismissed as a feminist excess.

Geetika realises that her curiosity and quest for freedom have led her up a slippery slope and this book is about the incremental costs of chasing one’s dreams. The book ends on a somewhat sombre notes with Geetika giving up on dreams of middle class marriage which would severely limit her choices. The unconventional and difficult choices she makes also demonstrate the influence of feminist staff rooms where many women– colleagues and associates — have made difficult and unconventional choices. In their company, Geetika realises that she has let herself drift into a relationship which would negate any exercise of agency on her part. It is in part, her recovery of her intellectual freedom to think and write authentically that constitutes her higher education.

The novel also offers us a social satire of ‘higher education’ in the premier institutions of Lutyenabad, replete with references to Capital University and Jana University. This is an insider joke with barely veiled references to actual universities in Delhi. Further, the academic pretensions of many academics who unleash fancy theories, which they have barely grasp themselves, on their hapless research students, are called out. Literary references pepper the text where Roland Barthes’s essay “Striptease”, a masterpiece of structuralist criticism, actually refers to a stripping of Geetika’s professor of her pretensions of having been at Sorbonne .

The Higher Education of Geetika Mehendiratta is a sharp, accurate, searing and witty coming of age story, a bildungsroman, which is unabashed in its honesty about an ambitious young woman’s journey to self-realisation. To quote from the Author’s Note, “Geetika, my outspoken protagonist, questioned and challenged, and the issues she grappled with are by no means resolved till date.” She continues, “Young people continue to face similar dilemmas: career or family, feminism or femininity, love or rebellion.” Geetika’s story is still relevant and contemporaneous, ”adding the heft of history to present-day conversations on marriage and partnership.” It’s a coming of age story that resonates far and wide into the twenty-first century.

Click here to read an excerpt of the novel.

Meenakshi Malhotra is Professor of English Literature at Hansraj College, University of Delhi, and has been involved in teaching and curriculum development in several universities. She has edited two books on Women and Lifewriting, Representing the Self and Claiming the I, in addition to numerous published articles on gender, literature and feminist theory. Her most recent publication is The Gendered Body: Negotiation, Resistance, Struggle.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International