By Somdatta Mandal

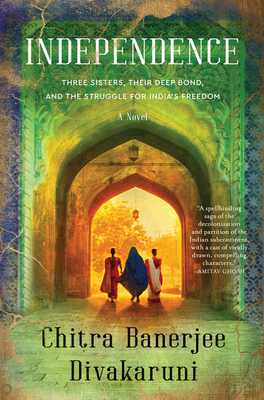

Title: Independence

Author: Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

Publisher: Harper Collins

Over the last two or three decades, the Indian American writer, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, has managed to carve a niche for herself by regaling in stories of cross-cultural issues prevalent in India and the United States with special emphasis on experiences of diasporic immigrant women. Though most of her stories are women-centric, with time one notices a gradual tectonic shift in her selection of themes. Initially she would write on problems of immigration and culture clash plaguing Indians in the New World. In Palace of Illusions, she went back to the Indian epic and narrated the story of the Mahabharata told from Draupadi’s point of view. In her novel The Forest of Enchantments, she brought Sita at the centre of the epic narrative The Ramayana and accorded her parity with Ram, revealing her innate strength. Then she took recourse to Indian history and rebuilt the story of Maharaja Ranjit’s Singh’s empire in Punjab narrating it from the viewpoint of Rani Jindan Kaur, his last wife as one of the most fearless women of the nineteenth century. Apart from the available historical data, she filled in The Last Queen by imagining many things Jindan would have said and done and thus painted a complete picture of a woman from all perspectives. A perfect blending of fact with fiction, the novel interested all categories of readers, serious and casual alike.

Now with Independence, Divakaruni widens her canvas to tell us the story of a doctor’s family and his three daughters against the freedom movement in India, particularly Bengal, beginning from August 1946 till the epilogue in 1954. The story of India’s independence is narrated through the eyes of three sisters, each of whom is uniquely different, with her own desires and flaws. They live in a rural village Ranipur and right at the beginning of the novel, which is divided into five parts and an epilogue, the author manages to give us the idyllic ambience of the place in very selective poetic language:

“Here is a river like a slender silver chain, here is a village bordered by green gold rice-fields, here is a breeze smelling of sweet water-rushes, here is the marble balcony of a grand old mansion with guards at its iron gates and servants transporting trays of delicacies up the stairs, here are a man and a woman on carved teak chairs. Here is the country that contains them all.

“The river is Sarasi, the village is Ranipur in Bengal, the mansion belongs to Somnath Chaudhury, zamindar. He is playing chess with Priya, daughter of his best friend, Nabakumar Ganguly. The country is India, the year is 1946, the month is August.

“Everything is about to change."

Doctor Nabakumar Ganguly is an idealist and with his practice in their native village Ranipur, where the family resides, he also treats patients in a slum region in Calcutta. He is highly regarded but earns little as he refuses to charge patients without sufficient means. His wife Bina complains about this but supplements the family income by making exquisite quilts for sale and gifting them to those in need. Among the three daughters, Priya is intelligent and idealistic, and resolved to follow in her father’s footsteps she wants to become a doctor, though society frowns on it. She is fortunate to have the support of zamindar Somnath Chowdhury, her father’s best friend. The eldest daughter Deepa is very beautiful and is determined to make a marriage that will bring her family joy and status. The third daughter, Jamini, is devout, sharp-eyed, and a talented quiltmaker, with deeper passions than she reveals.

Theirs is a home of love and safety, a refuge from the violent events taking shape in the nation. This idyllic setting changes rapidly, as the violence of Direct Action Day in August 1946 takes Nabakumar’s life and introduces fear and a communal bitterness in the once largehearted Bina’s veins. Soon their neighbours turn against them, bringing the events of their country closer to home. Deepa is estranged from her mother and eventually isolated on the other side of the border in what becomes East Pakistan, when she falls in love with Raza, a Youth Leader at the Muslim League. As Priya is determined to pursue her career goal, her attempts to get into medical school in India are thwarted by a gender bias, and she finds herself at a college in America. But due to several reasons she cannot complete her degree there and comes back to India to run the clinic where her father worked. And Jamini attempts to hold her family together, even as she secretly longs for the handsome Amit, her sister’s fiancé. When India is partitioned, the sisters find themselves separated from one another, afraid of what will happen to not only themselves, but also each other. It is only then that they understand what it means to be independent, and the price one must pay for it.

After a lot of twists and turns to the story, including smuggling of arms and rescue mission on the Ichhamati River dividing the two Bengals, Amit shot to death, by the time we come to the Epilogue it is 1954 where we learn about Deepa’s daughter Sameera, Jamini’s son Tapan, Deepa managing the zamindari estate and Manorama and Somnath eager to find a suitable match for Priya when she tells them that she is happy as she is now. Feminism, communal amity, empathy, and self-growth are among the requisite qualities Divakaruni identifies for both a country and a human being to be truly independent. Though set in households more than seventy years ago, towards the end we still find some hope. The Postscript to the story is rather interesting as it comes even after the epilogue. It reads thus:

“Here is a river. Here is a wind rising. Here is a village. Here is the year. “The river is time, ebbing, flooding. The wind is memory, it can carry flowers, it can carry flames. The village is the world, and you are at its centre. The year is now. “What will you do with it? What will you do?”

As a Professor of Creative Writing in an American university, Divakaruni has gained the expertise of playing her cards well – her narrative technique in each of her novels and short story anthologies preaches what she teaches – the saleability and marketability of a book in this electronic age should be of utmost concern. Like her earlier novel The Oleander Girl, which seemed to have been written as a sort of film script in mind, (incidentally two other novels are being made into motion pictures at the moment), Independence too seems to follow suit with the right amount of ingredients necessary for promoting the book to different kinds of readers and in different forms as well. One is therefore taken by surprise to find a QR code even before the Contents page which tells us to “Listen to the soundtrack for Independence. A playlist of songs that inspired the freedom movement.” For her Western readers, Divakaruni managed to blend history and fiction very well where along with the fictitious characters we get to read about Mahatma Gandhi and the Noakhali riots, Sarojini Naidu, Nehru and others as they played their parts in the freedom movement. Here we find Priya actively engaged in conversation with Sarojini who gives a letter of recommendation to Bidhan Chandra Roy to help Priya to run a clinic.

One praiseworthy aspect of the novel is how Divakaruni manages to give us details of the streets and sounds of Calcutta – the Calcutta of the 1950s with her double decker buses, the shops at New Market, the quaint little restaurants with curtained cubicles to maintain privacy in a public place – all brought back from memory of the city in which she was born and brought up. The novel is also full of translations of several patriotic songs in Bangla which the swadeshis sang during that period. Several lines from Tagore’s songs are also interspersed to express the moods of characters – a technique used by Divakaruni in some of her earlier fiction as well. The exoticism of India, especially rural Bengal of the time is deftly portrayed through many other incidents of killing and looting at different regions of undivided Bengal. As for her Indian readers we are given the story of Priya’s brief stay in America to study medicine at the Woman’s Medical College in Philadelphia where along with her homesickness, we have Arthur, a lovelorn American doctor, who lends her support and patiently waits for her to come back to him as “his heart has been empty” without her.

Despite such manipulations to the story to bring in as wide a canvas as possible, including sufficient examples of Hindu-Muslim amity and hatred as well, the novel remains a page-turner no doubt and can be recommended for its lucid and racy style of narration, something that Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni excels in.

Somdatta Mandal, author, critic, and translator, is former Professor of English at Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, India.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International