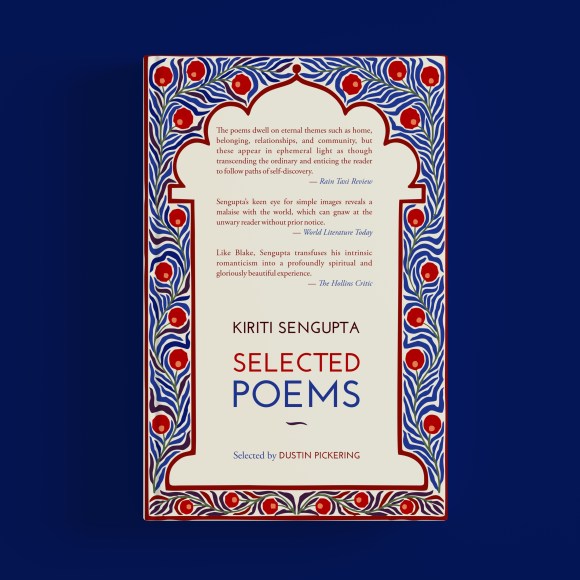

Book Review by Pradip Mondal

Title: Selected Poems

Author: Kiriti Sengupta

Publisher: Transcendent Zero Press (Texas)

Sir Philip Sidney, in his An Apology for Poetry, argues that the primary purpose of poetry is to “teach” and “delight”. Kiriti’s Sengupta’s Selected Poems serves both purposes though the poems do not preach at any point but leave the readers mulling over the ideas with the play of words. The book contains more than 125 poems, selected by Dustin Pickering, a writer and the founding editor of Transcedent Zero Press. The content covers an eclectic range of subjects—from personal musings to ecology, memory to myths and more — mostly republications from his earlier collections and some from journals.

An award-winning poet, publisher, editor, translator and critic, Sengupta believes himself twice-born as he states in his poem of the same name — ‘Twice Born’, written specially for this collection. He has embraced the calling of a poet, forsaking the lucrative profession of a doctor. It’s not that he doesn’t vacillate: “The ink has dried on the paper; the pot can’t be refilled with scribbles. Do I now surrender my pen?” But poetry is his vocation; it would sound ludicrous if someone could ask a noted poet, “What if you weren’t a poet?”(“Intrinsic’)

There is a sense of flow in the poems despite his stylistic terseness. Water permeates his poetry. The poet believes: “…water is achromatic and otherwise called life.” As the poet is a deep observer of nature and its surroundings, he observes that water carries out its own duty: “Water has no call, no décor either; it floats the bone and/ the ash free.” In ‘Evening in Varanasi’, the poet assigns the water of the Ganges with exceptional qualities: “The water here is not/a fire extinguisher. /Flames rise through the water.” He connects the water to the Sun: “O Sun, I remember/I’ve bathed your feet/with the water of the Ganges”. ‘River of Tears and Mother’ airs the deep concern about the recalcitrance of those who ignore ecological issues: “Ganga has her stories to tell;/wish she had someone to listen to her.”

Ecological strains seep through Sengupta’s poems. In ‘The Pillars of Soil’, he draws a fine connection between human beings and trees through the image of the roots. The poet invokes a supreme spirit: “the world would need another maestro/who could sing for the seasoned flesh—/those who walked the earth—/whose roots ran deep into the ground”. In ‘Hibiscus’, he evocatively draws a curious connection between the colour of hibiscus flower and human blood: “…I’ll bloom/like a hibiscus:/the blush will endorse/my bloodline.” The epigraph of the poem, translated by Sengupta from a poem by the noted ‘rebellious’ Bengali poet, Sukanta Bhattacharya, re-enforces his stance.

Concern for extreme air pollution in cities yields sardonic poetry: “Nature made the nasal frame fragile. /How do they breathe the vain air?” He also highlights pollution caused by plastics: “The earth has grown plastic. Water takes eons to seep”.

Some of Sengupta’s poems convey a sense of domesticity. “Clarity”deals with gastronomy as the poet succinctly invites the reader to succor ghee with all their five senses. In this piece, the poet reminisces about the aroma of ghee that his mother used to prepare. The poet here compares his mother’s organic ghee with his organic memory: “So organic is my memory—/the granular residue lifted us to heaven. /Ah! Pious Ghee, and incorrigible.”

In poems such as ‘Experience Personified’, the poet records his experience of the commonplace things: “Tiny droplets envelop my feet/and permeate the toes. /I don’t call it a feeling, I will name it/my experience”. It reminds a me of lines by Tagore: “But I haven’t beholden/what lies two steps away from my home/on a blade of paddy grain, a dazzling drop of dew”. Sengupta also doesn’t shy away from the recent happenings in India. In ‘The Untold Saga’, the poet recalls the abominable “Nirbhaya episode” and rues that, unlike Durga, Nirbhaya could not create an epic due to her untimely death.

The poet turns metaphysical – almost like John Donne[1]— when he asserts, “I now look beyond the flesh, bone and keratin, /I’ve been told/the finer body dwells undressed.” Though most of the poems are contemplative, the book offers some light-hearted ones too: “To my complete bewilderment, if the ghost appears, I’ve decided to offer it a chair first, and then I’ll plead, ‘Take a seat and relax! Let us share our stories.’” In ‘Gravity’, the poet offers a lighter note for the turbulence caused in the aircraft due to the inclement weather. He gives solace to his terrified son: “Relax, Bumps help us/ realize the earth.” In a haiku, punning on the word ‘wisdom’, the poet realises that it’s a test of a surgeon’s wisdom to pluck out a wisdom tooth (biologically called ‘the third molar’) of a patient.

Sengupta’s Selected Poems is a fabulous collection. These poems are like chosen seeds that contain intrinsic vigour to sprout through the age-old concrete floor, giving a message of hope in the face of all odds. Sengupta’s penetrating observations, coupled with his poetic prowess, can be vividly experienced by delving into the rich treasures hidden in between the covers.

.

[1] John Donne (1572-1631), Metaphysical poet

.

Pradip Mondal teaches at L. B. S. Govt. P. G. College Halduchaur, Nainital (India). He has been published in journals like Suburban Witchcraft (Serbia), Muse India (India), and Indi@logs (Spain).

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International