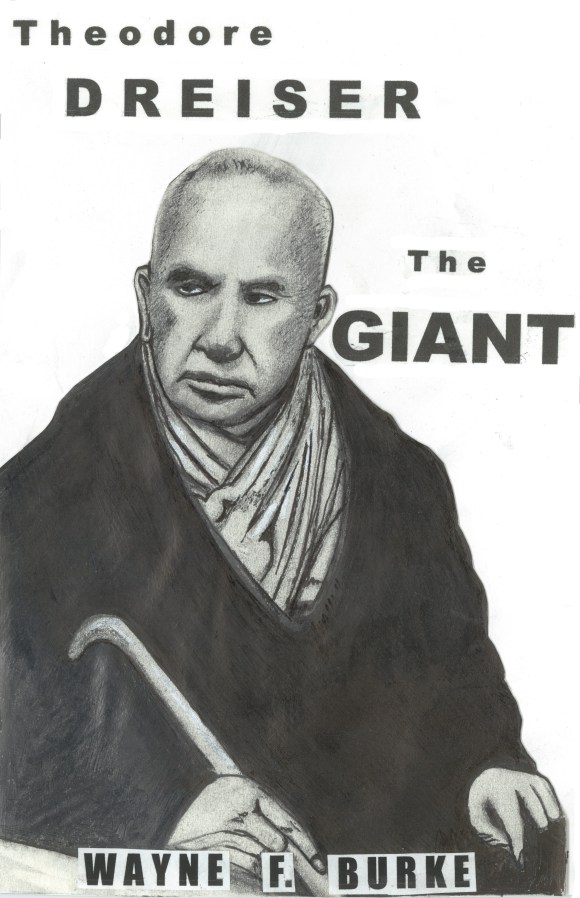

Title: Theodore Dreiser — The Giant

Author: Wayne F. Burke

Theodore Dreiser (1871-1945) reached apotheosis of his literary endeavour with his 1925 publication An American Tragedy. In the following twenty years, until completion of the The Bulwark in 1946, nothing he wrote remotely equaled the power of the tragedy. His opus plus Sister Carrie has become a classic—so too Jennie Gerhardt to a less heralded extent. Some of Dreiser’s short stories, such as “Nigger Jeff”, “St. Columba and the River”, and “The Lost Phoebe”, could stand on their own in any American or world anthology. Due to its narrative thrust and other attributes (powerful romance), The Financier was and is the best of Dreiser’s ‘Trilogy of Desire’ (including The Titan and The Stoic). The first three-quarters of the autobiography Dawn made for compelling reading, as did all of the essays in Twelve Men. The Bulwark was and is a minor classic, truncated but yanking at heart strings as adamantly if not for as long as any of Dreiser novels. Newspaper Days, the second volume of his autobiography is a baggy and verbose twin of the heavily, and unfortunately edited, A Traveler at Forty.

“The last great American writer of Melvillean dimensions,” Jerome Loving wrote of Dreiser. Dimensionality and similarity is each writer’s search to uncover and understand the phenomenon of existence. It’s a spiritual quest, though neither men have any sectarian belief (Melville nominally Unitarian). What is and to whom does the “oversoul” of Emersonian transcendentalism belong? To Dreiser, the grand protagonist life itself suggests a something else: God or gods perhaps, behind the display of natural phenomenon. Hs opus suggests that God or gods, or the “Creative Force,” used humankind for his, her, its own purpose; a purpose hidden from humankind’s limited understanding; also theorising possibilities of additional God or gods in the background making use of, let us say, “primary” God or gods, for a like inscrutable purpose.

In his last years Dreiser looked through a microscope for clues to the phenomenality of being—to unravel mysteries of life. Switching gears mid-career, he became an explorer of consciousness who preferred the company of scientists to that of literary brethren (to the detriment of his art, I must add).

In Dawn, Dreiser theorised that humankind was an invention—a schemed-out machine, useful to a larger something. This theory marked his turn from an early mechanistic belief in universal proceedings to consideration of an oversoul, or creative intelligence, behind or causative to universal phenomenon.

But what “soul”? What cause? What intelligence? Ahab[1] tried to tear the veil that covered the quondam source; tried to expose the phenomenon of so-called “reality,” but being only a man, and mortal, failed—dying in the process. What is the symbolism of the great whale’s whiteness but a concealing veil thrown over appearances? Melville’s scientifically, scrupulously dismantled his leviathan part by part, yielding naught as to mysteries of origins and unquantifiable organic processes, while Dreiser wandered over the same dry speculative desert (as Hawthorne noted) too honest to be or do otherwise.

Dreiser had his own mystic creed; refusing to conform to any formal doctrine—his views in later years influenced by Quakerism, Hinduism, and Christian Science (which his wife “Jug,” and his character Eugene Witla of The Genius came under spell of). In Newspaper Days, and in a sour mood, he wrote, “Religion! What a mockery! Why pray? Of whom to ask? The one who loaded the dice at the start?” Elsewhere in that same book—and in a better mood—he wrote, “There is a sower somewhere. Is it planet, gas, element, fire? It gardens and sows—what is its plan, and why?”

Like many ex-parochial students, Dreiser had a profound dislike of Catholicism and her rituals. A dislike engendered, in Dreiser’s case, by scorn of an ineffectual father, John Paul Dreiser. In Dawn, Dreiser wrote of Catholics with ossified brains who rejected natural emotion as sinful; who spent inordinate amounts of time on their knees praying to an immense and inscrutable something which cared not for their adoration or supplication.

He denied sectarian pretense to divine authority and wrote about how little there was to the Christ legend aside from artistic spectacle. Ritual and churchly dogma infuriated him—particularly angered by the priest who at first denied Dreiser’s mother burial in the sacred grove because she was a lapsed Catholic.

Dreiser despised religion in the form of Catholicism as much as he came to despise oligarchy—though early in his career celebrated the power of the oligarch in the character of Frank Cowperwood, of the ‘The Trilogy of Desire’, apotheosis of laissez faire capitalism run amuck.

Will Dreiser’s work survive the muddle of brave new world exigencies? I hope so. The slow relentless and inexorable pace of his stories, with their accumulation of details, are or seem anathema to the cyborg-screed of flash fiction sound bites in the blogosphere, but the stories he told—all having to do with vagaries of the human heart—though perhaps out of vogue, will never not be relevant to the human oh so human condition.

[1] From Melville’s Moby Dick

About the Book:

Theodore Dreiser – The Giant, is an explication, exegesis, of the fiction of Dreiser plus much of his nonfiction. Included are synopses of each title. Between considerations of the work is a biography of the writer. (Note: Dreiser could be, in his work, pedantic and humourless: this study is neither.)

About the Author:

Wayne F. Burke writes both poetry and prose. He is author of 12 published poetry collections–most recently Whatever Happened to Baby Wayne? Hog Press, 2025; two works of fiction–most recently No Tab For Sully, a novella, Alien Buddha Press, 2025; and six works of nonfiction–including Theodore Dreiser – The Giant, Cyberwit,net., publisher, 2025. He lives in Vermont (USA).

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International