Narrative and Photographs by Prithvijeet Sinha

Solitude hardly alienates us when our mind is at peace. It travels with us. It’s a profound pursuit when one embraces the solitude of a city like Lucknow. Our fates travel with the boat of time flowing on the languid currents of the river that flows through the town, Gomti.

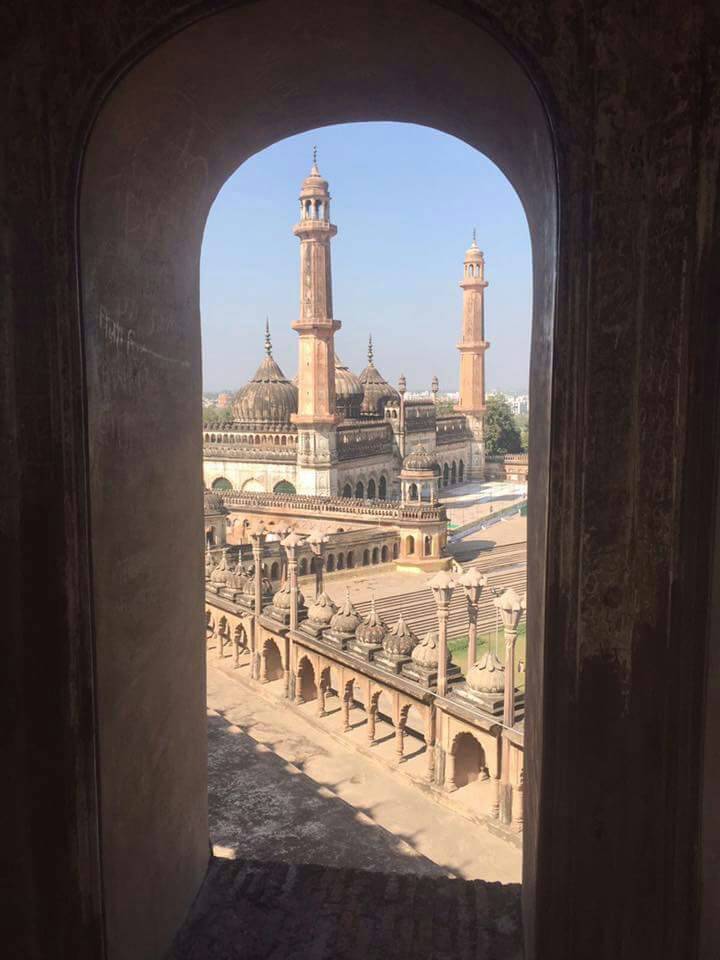

As someone born and brought up here, it’s a great joy to walk in the footsteps of those who gave exquisite shape to its countless monuments, their chisels and hammers turning stones into works of art, adorning the city with centuries of hard toil that created exquisite beauty. This beauty hewn into the Bara Imambara enchants me anew everytime I stroll through the compound. Those limestone pillars, graded by years of construction in its classical heyday, are miracles of human hands that mesmerise. The golden paint adorning its architecture courts the sun and that great orb of light gives in to the invitation to be eternal friends for life.

The Bara Imambara, also bestowed with the title of “Asafi Imambara”, was made by the king Asaf Ud Daula out of benevolence. He commissioned the building in order to employ the drought-stricken populace of the city in the 18th Century. Very soon, this structural project expedited as a corollary to supplement the dwindling fortunes of the region became more than a philanthropic feat. Over the centuries, Bara Imambara became a royal palace, a seat of power and knowledge and a quintessential component of the Awadhi [1]identity. It’s convenient to say that it’s the axis around which the entire city revolves. It’s the architectural apex around which Lucknow sculpts its identity with each era.

Throngs of revellers travel across the city to savour its beauty and historicity. The Imambada keeps its tryst with timelessness sacred, giving every discerning eye moments to cherish, feel the same timeless energy course through their mortal bodies, giving them the gift of the spiritual. Then there’s the mystical side to it where on each visit tugs my heart. It’s as if from some intensely private part of the soul emerge these words, “Thank God, you are alive to see it. Thank God that you were born to witness such sublime beauty.”

The story of arches, pillars, doorways, the zigzagging mysteries of the Bhool Bhulaiya — its fabled labyrinth, hallways that make a single lighting of the match echo with precision across great distances and the cool atmosphere that envelops it even on muggy or scorching days make it a unique experience. But as the horizon spills its canvas around it and the panorama of life becomes a live orchestra of colours, the Imambara transcends its solemn sanctity as the abode of imams, transcends the rails of religion to diffuse faith to every corner. From some high point in the parapet, when you look straight at the city, each angle reflects the union of the divine and the mundane. It’s a grand gesture that this timeless solitude is something that can be felt even among millions of other feet and voices. It’s the solitude of the dark alleys and the baoli or stepwell within these enchanting premises. It’s this solitude gliding with the birds above the soaring pillars and dome of the Asafi Mosque, making the secular transport tangible in the mouths of those who drink in the air contained in the edifice of this monument.

I may be a dreamer but, in a city, where so many parts feel like a dream come true, the Hussainabad corridor hosting Bara Imambada is immune to modernisation’s whims or the gritty nature of our societal churnings.

As tongas[2] carry dignified visitors on cobblestone roads, Lucknow’s epicenter of culture beseeches us like a best friend to partake in the poetry of its eternal axis. Which is why I always like to walk towards it, crossing a stretch of the road that finds beautiful buildings, parks, wide roads and secular spots lead towards that most handsome of structures. Time stops here yet moves like ripples. Time is of the essence. A lifetime of meetings with the Imambada makes one reconcile with the inherent meanings behind one’s attachment to Lucknow and its Awadhi cheer. I’m fortunate to live and tell the tale, a modest man made to feel grander by these inflections of architecture, stillness and cosmic solitude that only this city has to offer. The Imambada absorbs all of these inflections and stands in good stead, telling me, “You are not a dreamer, son. Your sense of your world is intimate to a fault. Come to us. Come again. There’s so much to seek from each other…”

[1] Awadh was the ancient name of Lucknow

[2] Horse drawn carriages

Prithvijeet Sinha is an MPhil from the University of Lucknow, having launched his prolific writing career by self-publishing on the worldwide community Wattpad since 2015 and on his WordPress blog An Awadh Boy’s Panorama. Besides that, his works have been published in several journals and anthologies.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International