With its four-storey outlet in GK-2, Ajay Jain has made Kunzum the new happening place for book lovers in Delhi-NCR. He converses with Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri about his journey and about making brick and mortar stores viable in the era of Amazon as the writer browses through the different sections of the bookstore.

It is a bookstore unlike any I have been to, and that’s saying a lot. I visited it first sometime in December 2022, when it was still a work in progress, and even then it was stunning enough for me to get my aged parents, who need walking sticks, and my wife, who at the time was nursing a broken ankle, to visit this as a new year outing on 1 January 2023. Since then Kunzum at M Block Market, Greater Kailash 2, New Delhi, has grown to four floors spread over 10,000 square feet. The first floor is the regular bookstore, the second the Penguin bookstore. The third the ‘Theatre Kunzum’ – a 125-seater events hall – and the fourth an eighty-seater theatre, with plans for a café. There are other Kunzum bookstores which are a more modest 2500 square feet each. The original Kunzum Travel Café is approximately 500 square feet.

I enter it and am transported to a book lover’s paradise. Its very affable owner, Ajay Jain, and brilliant curator, Subir Dey – who generates in me a huge complex with his awareness of books and a hole in my pocket with his recommendations for the same – have time and again asked me to work out of the store. Which I would have gladly done, but for the fact that, one, it is impossible to get any work done once you enter its precincts (the only work it allows is browsing its shelves), and, two, I fear that I will end up spending all my salary at the store.

What makes it remarkable is that Ajay can visualise a store chain like this in this day and age where we hear a constant refrain of brick and mortar stores closing down. Of how difficult it is to sustain one in the age of Amazon. Most of the major bookstores across the country have devoted a large part of the space to stationery and toys. Ajay is determined not to do that. As far as he is concerned, a bookstore is a bookstore. And there will be no dilution of the space. As Ajay says, “I was very clear from day one. We will not sell teddy bears, stationary, croissants (chuckles). It might be a slightly steeper learning curve, but we want to learn how to sell more books. If I’m not selling enough books, why am I in this business? I could have invested this money somewhere else. For me, it’s a social mission to push more people to read. If everyone, every human being on this planet, reads books, it would be a much better place to live in. When we read books, we also challenge rampant consumerism – we are taking the money away from buying other stuff to buy books.”

Given the quite extraordinary range of books, including rare and collectors’ editions – I picked myself a mind-blowing one on iconic book covers, The Look of the Book, by Peter Mendelsund and David Alworth – Subir Dey, the curator, is the backroom star of the show. A quiet, self-effacing book lover, Subir says, “I have been doing this for myself, at home, before Ajay started the bookshops. One day, I just picked up the phone and asked him, how can I help? Then, there is the community angle. I talk to fellow bibliophiles both online and offline who point out all the amazing editions of great books. The curation team at Kunzum is indispensable. Everyone has their favourite genre and we all diligently keep track. The classics and graphic novels are an easy target because of their popularity. Then there are collected works and anniversary/commemorative editions that we try to keep track of. Publishers help us with that too. For example, the Dune series picked up when the new movie came out. There are so many beautiful editions of the book that it is hard to choose. There are graphic adaptations of long-form novels like 1984, Animal Farm, The Kite Runner that we tracked down and have in stock. These are great books for someone who is intimidated by the traditional long-form novel format. This could be their gateway drug into reading and Kunzum would love to get them addicted. Special editions are a brilliant gifting idea. Books are the best gift you can give to people. Most of us have friends who are avid readers. These special editions are a very thoughtful gift. We tell our customers to bring a book to a party full of people who are bringing bottles of wine. We all used to give and receive books as gifts, growing up. Those books shaped our worldview. We are rolling out ads on social media to highlight the special editions available with us and pretty soon you will see more of these titles highlighted not just online but in our stores too. There is a demand for it, we have seen an uptick in the interest among buyers who are looking for specific edition of their favourite books and our team is happy to track them down.”

The Beginnings

Ajay Jain: I have a background in engineering and management, so I worked in the IT industry for five years. Then I got into sports management, and did that for five years. At the age of 31, I dropped everything and moved to the UK to study journalism. I did my master’s in journalism there. I came back in 2002, worked for the Express group, started a youth newspaper, got into blogging and freelance writing – mostly business and tech writing – which I did till about 2006–07. I was one of the earliest professional bloggers in the world. As a journalist/blogger/ influencer (the word wasn’t there at the time), and as somebody who wanted to write books, I figured I wanted to do something where I could create more of a legacy.

Early Reading

Ajay Jain: Growing up, I read the usual staple. You had your Enid Blyton, Nancy Drew, Hardy Boys, Famous Five. Unlike my classmates, I never read Agatha Christie or PG Wodehouse, but I had read all of James Hadley Chase by the time I was in Class 8. My headmaster used to ask me why I was borrowing these books from the library. I did so because they were there! I read a whole mixed bag of books in middle school and high school, even in college. I read Sidney Sheldon, Jeffrey Archer, Ayn Rand – a mixed bag. Anything that caught my fancy.

Travel Writing

Ajay Jain: Around 2007, at a personal and professional crossroads and unable to relocate from Delhi, I said to myself, ‘Okay, let me do the next best thing,’ and I became a travel writer. I’d done a few short road trips around India, and I was really enjoying travelling. Since I’d also learnt photography, I was doing a lot of that. I thought, why not make it a profession? So I hit the road.

I didn’t want to write a Lonely Planet kind of book, and I also didn’t want it to be a literary piece. I was thinking of my own format. The first trip I actually went on was to this place called Spiti in Himachal. I spent a night in Manali, and then headed for Spiti. I crossed the Rohtang Pass. Till then, it was fine because there were other people. I’d never done that kind of terrain ever. I drove for hours in a high-altitude desert area with no road signs, no mobile signals, nothing! Just a track where you followed earlier track marks. After a while I realised I was lost!

The Defining Moment – the Birth of Kunzum

Ajay Jain: I just kept driving, not coming across another human being for hours. Imagine not seeing another human being for hours in a country like India. Suddenly I came upon a plateau, upon a sign that said ‘Kaza’, which was where I was headed! That spot, where I stood, was the most astounding place. As I looked around, the only thing I saw was snow peaks, Buddhist flags flying, complete silence. It was breath-taking. I thought to myself, if this is what the planet is, if this is what India is, I want to be a travel writer. In that moment, not only did I find my direction to Kaza, I found my direction in life as well. The spot where I stood was Kunzum-La.

After I returned, I called my blog Kunzum.com. A little accident in technology worked in my favour. I had reserved the domain called traveltattoo.com as my travel blog. For some reason, the registrar didn’t inform me that my domain was up for renewal. It got taken by someone else. In losing traveltattoo.com, I got Kunzum.com. That’s how the name Kunzum came up.

Kunzum Gallery, Hauz Khas Village

Ajay Jain: I did a few shows for my photography at places like Habitat Centre and got a decent response. I was encouraged to open a place of my own and came across a place in Hauz Khas Village. I picked it up in 2009 and opened up a gallery there. On the first day I sold a print, and then for the next year or so I didn’t sell a single thing! So, I was just sitting there with some friends, mulling over what to do, and we realised that all the people who bought my prints in Habitat just happened to be passing by. They saw the prints, they liked it, and bought it on the spot because the prints weren’t very expensive. I decided to do something there (in the gallery in Hauz Khas) that would get people in. That’s when we decided to offer seating in the gallery- let people come in, enjoy free WiFi, etc.

We set up a small library so that people could borrow books, and decided to serve up tea, coffee and cookies. We thought we could pay for all of this. When we looked at the numbers (and crunched them), we realised that if we pay for everything and a certain number of people come, and nobody pays, we will be out of pocket by so much, but will have acquired some customers for that price of coffee and cookies and all.

Funding the Enterprise

Ajay Jain: I was still freelancing, and had been investing over the years with whatever I’d saved from my various ventures. I was just getting by. We decided to rebrand the place in Hauz Khas from Kunzum Gallery to Kunzum Travel Café. The place took a life of its own. A few days after we opened, someone came in asking if we could do a poetry reading, to which I agreed. Before we knew it, we had over 200 events happening in the café every year. There were all sorts of events – book launches, film screenings, poetry events, talks, etc.

We were clear about the financials. If you benefited commercially from it, you pay us. If there was nothing commercial, if you didn’t have the budget, okay, you could use the space anyway (if the event was suitable). We kept it flexible. My main motivation was to get people in, to see my photography and my books, which were sold at the café.

Bookstore Chain in the Time of Amazon

Ajay Jain: During the pandemic, I was reassessing a lot of things. I have always believed that just because we are doing something well, we should not be doing it all our lives. With the pandemic, I had to shut Kunzum Café for over two years, making do with a skeletal staff throughout. I wrote my first novel. I kept wondering: how do I find an audience for my books? No matter how big your publishers are, or how big you are as an author, you still need to find your own readership. Then I thought, why don’t I set up a book club? A national book club, something that would have many people. The response came in quickly as well. I enrolled a couple of thousand members.

That’s when I thought, why don’t I turn Kunzum Travel Café into a chain of reading rooms? Build a model where we create reading rooms across the country, where people come and sit and read. The numbers didn’t add up though. There was no model that would make this sustainable for me. Enough people wouldn’t pay enough money to make this a library-type of model. It wouldn’t work in this climate, especially when real-estate had become so expensive. I had learnt how to build a community, how to bring people together through Kunzum Travel Café, but I didn’t know how to monetise it.

People had asked me, will there be more Kunzum Travel Cafes? Will there be a Kunzum Travel Café franchise? For me, Kunzum Travel Café was more of an exercise in personal branding. For the external investor, there would be no ROI since the only one benefiting from Kunzum Café was one Ajay Jain. In the process, I started making money doing brand endorsements through Kunzum Travel Café. It was more like a PR agency, so the only guy benefiting would have been me.

That is when I realised I should open a chain of bookshops! The model would be Kunzum Travel Café, but with a bookshop added to it. I did some back-of-the-envelope market research. There were people buying books, publishers doing business. In absolute numbers, there were more books being sold than ever before. I went to the bookshops which had good business – like Bahrisons, Faqir Chand, Midlands, etc. They had a huge legacy and were located in prime locations. I figured that I’d learnt how to make Kunzum Café in Hauz Khas a destination, and that I’d make this new venture a destination also. I didn’t really feel too daunted by this, I knew we’d figure things out as we went along. If I started asking too many questions, I would have been dissuaded immediately, so I thought that I’d figure it out on the road.

We have five locations. The GK one has four floors, so you can consider them either four stores or just one. At the core, the business model is simple – sell books, and sell enough books to make a profit. It’s still early days for us, we are on the way as we speak. I know that trends are right, and within this year we will be operationally profitable, so I’m not too worried about that.

I did a bit of reading, given that stores were closing all over the world, and the rise of Amazon. If Amazon did not exist, or if Amazon did not offer such discounts, many more bookshops would be open today. People would still prefer to walk into a bookstore for the experience of buying a book over buying it online. Because Amazon offers such discounts, most people think books are easier to buy online. I blame publishers squarely for this, not Amazon.

The Irony of Publishers Killing Bookstores

Ajay Jain: If books and readership are being challenged by other forms of entertainment, and readers are distracted, one needs to look at this as something cultural. That’s why experiences become important. Experiences are connected to physical spaces. That’s how you expand readership. Unfortunately, when I started interacting with publishers, I noticed that they show little intent to expand readership in society. They are making enough money not to think about expanding readership. It’s not enough for publishers to tell me, “Hey, I love what you’re doing at Kunzum Café.” They need to plug the discounting at Amazon, and the piracy of books. More than piracy, I think the discounting is a problem, which publishers can solve partly through lobbying, and partly through curtailing supply, if they want to. They own the product, and if they say no, that can change things.

The publishers’ argument is that they give the books to distributors to be sold, and these distributors are not within their control. The fact is, everyone is traceable. Publishers know who is selling their books, and can plug supply. If a reseller picked up a book on Amazon to resell, the publisher could tell Amazon to stop them. It could get into a cat-and-mouse game but eventually, it would dissuade them so much that the incentive to play this game would go down.

France Shows the Way

Ajay Jain: Look at what happened in France. The government in France forbade Amazon from offering discounts of more than 5 per cent on books. The French government realised bookshops were a national cultural asset. Because of this, bookshops that were struggling are now flourishing, and new bookshops are opening. This change came through legislation.

In India, if publishers want, they can move the Competition Commission, and say that discounting on Amazon is an unfair trade practice. In a country like India, where you have the MRP [Maximum Retail Price], if you can’t sell above MRP, how can you sell below MRP? Especially because all governments in India have the same stated position on FDI [Foreign Direct Investment] in retail, which is to ‘protect the small trader’. So, Competition Commission could look at how these discounting practices are putting businesses in such a precarious situation. If the publishers make enough of a song-and-dance about it, if they lobbied, if they took legal recourse, I think this issue can be resolved. We have a precedent in France now.

Financial Viability

Ajay Jain: When I was doing research, I wasn’t researching into whether I could open bookshops or not. I was researching how to make it viable. I had already decided I was going to commit to this venture. I’d started acquiring the real estate for it. I read someplace, “Bookshops don’t fail. Bookshops run by lazy booksellers fail.” In today’s day and age, not just books, you have to sell every commodity as an experience. You could be selling shirts, shoes, books, anything, because everything you want is available online. But if you want people to come to the stores, shopping malls, markets, you need to create that experience for people.

The Four Cs of Bookshop Design and Marketing

Ajay Jain: I have formulated what I call ‘The Four Cs of Bookshop Design and Marketing’. First is Configuration, which is basically the way you design the stores. If you look around, we’ve designed them in a way that the shelves don’t overwhelm you. There is enough space to move around, to sit down, to go through the books. You have browsing space and you can maintain a distance between yourself and the shelves. Not only is the vibe inviting, the design also allows you to discover books which you may not have discovered in an overstocked bookstore. The whole mood of being inside a bookstore is extremely important.

The second C is Curation. The kind of titles we select, the way we display them, and the way we help customers discover new material. Finding books customers were not looking for makes for a delightful experience. That is what will bring them back. These customers will say, “Hey, you know what? I went to Kunzum and found this great book! I loved it. It was money well-spent and time well-spent.” This is where Subir and his team come in.

The third C is Community, which we were doing at Kunzum Travel Café. We wanted to build a community of not just readers, but creators – writers, artists, designers, editors, everyone involved in creating books. Again, like Kunzum Travel Café, look at it like a larger cultural thing. So, bring in musicians, film-makers, puppeteers! We wanted to bring these people together to create a community.

The fourth C, Convene, aims to bring these people together for events. Ever since we’ve been fully operational, we’ve already hosted over 500 authors. We’re adding many more events, more programming, more partnerships, so that people can come and use our spaces. We make sure that there is enough space for people at our events, and that people don’t have to push bookshelves in order to be able to participate. We have dedicated spaces for events.

Since many people in my team come from the book retail industry, when the first store opened, the first question they asked was, “Sir, haven’t you wasted a lot of space?” The event space is going to be your brand ambassadors, your marketing agents. People will want to come for these events. We built the whole model on these four Cs. The signs are positive. People will come and talk about you, and be here, and will want to buy books from you. It’s just a matter of time before enough people will buy these books.

The Penguin Floor and Other Initiatives

Ajay Jain: In GK 2 we had just one floor, the first floor, a general bookstore, to begin with. Then an opportunity came to acquire the rest of the building above. Because the terms were attractive, I agreed. Then I thought, why not have thematic floors? One thought was that half of the second floor could be a graphic comic and art store, and the other half would be for children’s books, with the rest of the spaces above being dedicated to events. I was in the Penguin office having a general talk about multiple things. I really loved their office, so I said, “Look, it’s like a bookstore in itself.” I proposed that we should have an exclusive Penguin store. Penguin is one publisher with such range and distribution in books, no other publisher has ever come close. Their international collection is only increasing, and they have so much to offer. I don’t think the exclusive floor in our bookshop would have worked with any other publisher, just because no other publisher can offer the range Penguin has. They have graphic novels and comics – an important genre for us.

Then we got an offer from the top management, and I got excited. Like everything else in life, I ran with the idea, and decided to work out the viability later. The idea is that our bookshop showcases the best Penguin has to offer, incentivising Penguin to bring in their best in terms of their programming, their authors, and their events. It technically becomes a Penguin showcase. For us, it’s an opportunity to work closer with the world’s biggest publishing house. A few weeks ago, the UK Penguin team confirmed to me that this (the floor of the bookshop) was the only exclusive Penguin store in the world.

As part of a community, we’ve actually taken a lot of initiatives. One of them is called Book Bees, which is a book club for children, for kids up to twelve. Our children’s book section is called Kunzum Book Bees now. We also have a general book club called the Kunzum Book Club. Anyone can become a member for free. If you become a member, you get priority invites to events, we will give you first access to signed editions, which are always in limited supply; we will give you a little discount on our books, stuff like that. That’s part of the community-building exercise.

We launched the Kunzum CEO Book Club, where we’re getting corporates to come on board to encourage the culture of reading. The proposition being that all leaders are readers. If you want to nurture leadership within your organisation, you need to promote readership. We’re reaching out to them, asking them to buy books on a structured basis to distribute them amongst their employees, and maybe go even beyond that, by distributing them amongst their vendors, their customers, to spread the culture of reading.

We launched this programme called ‘Kunzum Key’ which is open to everyone, but primarily for creators of all kinds. You could be an actor, a dancer, a film-maker, a producer, an event-manager, a musician, anything! We give a free membership card that allows them to create at Kunzum – keep their own sort-of-office as long as they follow a fair-use policy. These creators can come, sit here, do their work, hold meetings, have interactions, brainstorm, showcase their work in some way. They will be offered free WiFi, which we don’t offer our regular customers. Every time these creators come they will be given a no-questions-asked complimentary cup of coffee or tea, and the bookstore will give them a very hefty 20 per cent discount on all the books they buy at the store.

Then there are the lit-fests. We are reaching out to every possible event where there are likely to be people who will buy books. We are asking them to make us their official bookstore partner.

Reaching Out to the Underprivileged

There’s a limitation to how many bookstores we can set up and how much we can do in each store. We don’t want to expand our physical spaces indiscriminately because we want to stay true to the culture we are trying to create. If we expand too much, or thin ourselves out, even if we get funding, which comes with its own pressures, we don’t want to lose our essence.

Our idea of expansion is to take Kunzum to potential readers. The corporate sector is a very obvious one. We’ve started doing small book fairs and events at different localities to promote the culture of books and reading at your doorstep. Schools and colleges are important to us. The intent is there. We’ve already reached out to a few schools, some of the DAV schools, where we did some events. There’s around a thousand schools there. Each school in the DAV chain cuts across all segments of society. We’ve also been approached by a few universities and colleges. We have a limitation of manpower. We want to make sure our manpower can pay for itself. We want to reach out to schools to, again, promote this culture of reading. If schools start buying at an institutional level from us, they can make books available for students who are not able to afford books. That’s where, again, we go back to the whole ethos of ‘Curation’ we are trying to create. Don’t just buy books that you think everyone is reading for the sake of being like everyone else. We’ll help you select books that you may not have thought of. I have been thinking of a programme where enthusiastic readers who are unable to afford books can be matched with someone who could fund their books. Of course, we will have to do it in a slightly more structured way. When I meet anyone from above a certain economic stratum, I see how privileged they are because they can afford to buy books but they are not reading books. There are people out there who want to read books…

At an LGTBQIA event that we had done, a guest who loves books said she couldn’t read anymore because of an eyesight problem. There was another young person there who wanted to read books but could not afford to buy. They just got chatting, they’d never met each other, and the former bought the book for the latter. She said, “I can’t read, but you can, so here’s the book for you.” How do we kind of institutionalise this programme? We’ll have to figure it out.

Regional Language Library

There are a couple of issues here. We will have a space constraint – where do we store it? Number two, how would we curate it? Because every language would require a different curator. In a city like Delhi, there would be enough Telugu readers, Bengali readers. But then, Bengali readers may want something other than the popular titles we might store. They might be looking for a larger collection. A lot of vernacular readers invest a lot in their respective languages. We might not be able to build depth to cater to that audience, so that’s a challenging situation to be in.

Going Ahead

We want to be present in every community – corporates, residential neighbourhoods, schools and colleges, etc. In a small way, we are sending books to rural areas too. For that to pick up pace, we need to look at it slightly differently. For now, we’re doing it in our small capacity. The whole idea is, irrespective of how many stores we have, we just want to go out there and get more people to read. Whether they borrow books and read, or buy books from Kunzum or not, let that be secondary. It falls upon every book lover to spread the good word, and encourage other people to read. Once you overcome that inertia and start reading, you stay with it.

(Published in multiple sites)

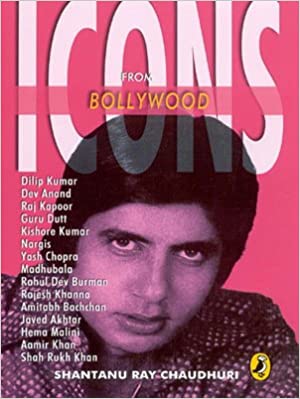

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema twice and the inaugural MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has contributed to a number of magazines and websites like The Daily Eye, Cinemaazi, Film Companion, The Wire, Outlook, The Taj, and others. He is the author of two books: Whims – A Book of Poems(published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin/Puffin).

.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International