Book Review by Satya Narayan Mishra

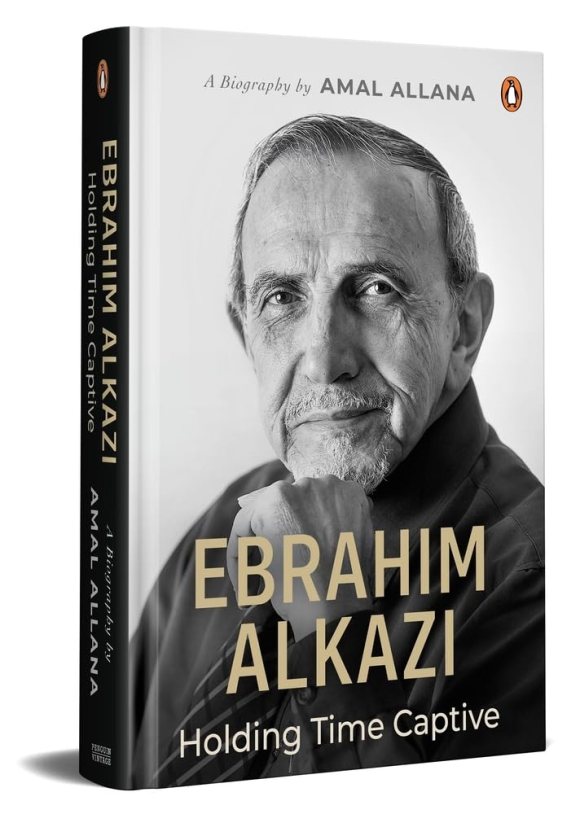

Title: Ebrahim Alkazi: Holding Time Captive

Author: Amal Allana

Publisher: Vintage Books, Penguin

During an extensive interview, Pankaj Kapur, the highly acclaimed actor, director and writer, nostalgically remembered his days in NSD[1] as a student in the 70s and of Ebrahim Alkazi who was the guiding light of the school as the Director from 1962-77. Mandi House was the vibrant cultural hub where the quartet of NSD, Triveni Kala Sangam, Sriram Art Centre and Kamani Auditorium breathed cadences of art, music, dance and theatre. As the presiding deity of NSD, Alkazi’s prodigious talent in all aspects of theatre except costume (where his wife was the moving spirit) brought his dynamic genius into the quest for intercultural and interdisciplinary thinking in artistic expressions that was both transformative and liberative for his myriad students like Sai Paranjpye, Nasir, Om Puri, Surekha Sikri, Uttara Baokar and Pankaj Kapur[2], who later on lit the stage and celluloid though their exceptional talents and skill. He would have been a hundred this month. Amal Allana, his daughter has authored a biography of her father, Ebrahim Alkazi: Holding Time Captive. The book makes an absorbing read.

She brings out Alkazi’s early encounters and reception by the Hindi Theatrewallas of Delhi in the early 60s. It is the story of a western educated Bombayite who was presumptuous enough to think he could teach Delhi theatre buffs a thing or two. As a second-year student, Sai Paranjpye recalls Ebrahim as a storm under whom a metamorphosis took place in the NSD overnight. Walking in to the den of Hindiwallah writers’ camp, Alkazi caught them unawares by picking up the works of the most cerebral and experimental of the Hindi new wave movement; Mohan Rakesh’s Aashadh Ka Ek Din[3]and Dharmavir Bharat’s Andha Yug[4]. Aashadh ka Ek Din, a play with a rural background, was the story of the Indian villager, whose lifestyle, pace and values were succumbing to the inevitable onslaught of urbanisation. The basic theme was autobiographical to Mohan Rakesh himself, where he identified himself with a classical playwright like Kalidas. This mix of history and the present entwined in to a single entity, was a modernist strategy that Alkazi too had attempted while contemporising myths. He exquisitely crafted the mise en scene[5]that sparkled with delicate, nuanced performances from young student actors such as Sudha Sharma as Mallika and Om Shiv Puri as Kalidas.

India had lost a war with China in 1962. Alkazi had chosen Andha Yug, set during the last days of the Kurukshetra war, when Aswasthama stood in rage, prepared to use the ultimate weapon to annihilate the mankind. It was just not the play’s topicality, its anti-war thrust that drew Alkazi to it. Alkazi tried to shrug off the baggage of European modernism he was carrying, embarking now on a foundational journey towards a deeper ‘discovery of India.’ Through Andha Yug, Alkazi came closer to learning about India’s value system and philosophy as explored in the Mahabharata, while Aashad gave him an appreciation of the artistic sensibility of the great Sankrit poet-dramatist Kalidas, India’s veritable Shakespeare. From now on, he would engage with the idea of India between the two polarities: India as a myth and India as a kind of documented reality. Alkazi was introducing the idea that theatre was a performance art, not literature performed on stage. He was creating a language of performance that was distinct from the language of words.

The making of Tughlaq and its staging in Purana Qila is a watershed event in the theatre landscape of Delhi. Alkazi was greatly drawn to Girish Karnad’s play Tughlaq. Karnad had confided in him how Tughlaq was the most idealistic, the most intelligent king ever to come on the throne of Delhi and one of the greatest failures also. And how in the early sixties India had also come very far in the same direction. Alkazi felt that this play effectively reflected the trials and opposition a visionary leader faced, while trying to function within a corrupt political scenario. The cast of Tughlaq had some of the most brilliant actors, each painstakingly trained by Alkazi himself. There was Manohar Singh who was playing Tughlaq, Surekha Sikri and Uttara Baokar were doubled as Sauteli Ma, Nasiruddin Shah as the Machiavellian Aziz, Rajesh Vivek as Najeeb. The young reporter members included Pankaj Kapur, KK Raina, Raghuvir Yadav, a veritable who is who of latter-day cinema. Tughlaq was staged in 1972 at the Purana Qila (Old Fort) in Delhi, utilising the historical ruins as a backdrop for the dramatic spectacle. This production is considered a landmark event in Indian theatre, combining history, politics and performance to create a commentary on the reign of Tuqhlaq[6] and politics of the 60s.

Nehru’s dream of reconstructing the nation needed a powerful and unitary concept of ‘nationalism’ to recognise all productive forces in the country. Culture was very much a part of the reconstructive process that needed to be systematised and brought under one umbrella and for this purpose, three national academies had been set up: the Sangeet Natak Academy, the Lalit Kala Academy and the Sahitya Akademi. The desire to modernise Indian theatre was part of the same reconstructive cultural policy. And Alkazi was the mascot of the theatre movement and Mandi House, the epicentre of cultural conflation and crescendo.

The Purana Qila festival in 1972, with Tughlaq, Sultan Razia and Andha Yug became the most talked about cultural event of the decade He wanted to offer both the hoi polloi and the cognoscenti, including burqa clad women, high quality theatre that did not conform to ‘popular taste’; theatre that had a social relevance, that both instructed and entertained. This was Alkazi’s ideal of what constituted national theatre.

There have many stars in firmament of Indian theatre. Ebrahim revitalised Indian theatre. Habib Tanvir, blended folk traditions with modern drama. Badal Sirkar revolutionised Bengali theatre by challenging conventional norms. They are like the great troika of Indian Cinema, Satyajit Ray, Ritwick Ghatak and Mrinal Sen.

Alkazi left NSD as it was denied autonomy by scheming bureaucrats. Allana brings out how Alkazi passionately believed that an artist belongs to no political party, and has no religious ideology. An artist has to distance himself from each one of these in order to see each one of these objectively. “And finally, he has to distance himself from himself.” He wrote: “ It is our duty and moral responsibility to study history dispassionately, but with a passion for the truth, with humility and with a profound sense of responsibility and to ask ourselves seriously: What is the legacy that we shall leave behind?”

[1] National School of Drama

[2] Well known Indian actors

[3] A Day in Aashadh (June-July) was a Hindi play that debuted in 1958

[4] Blind Age was a verse-play in Hindi written in 1953

[5] Placed on stage

[6] A 1964 Kannada play by Girish Kannad, translated to Urdu in 1966 in NSD and most famously performed for in Purana Qila, New Delhi, in 1972

Satya Narayan Misra is a Professor Emeritus and author of seven books. The latest, Against the Binary, was published in December 2024. He is a regular columnist and reviewer of books for several leading newspapers in Odisha and digital platforms likeScroll.in and The Wire. He was associated with the NSD in the 70s.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International