Book Review by Somdatta Mandal

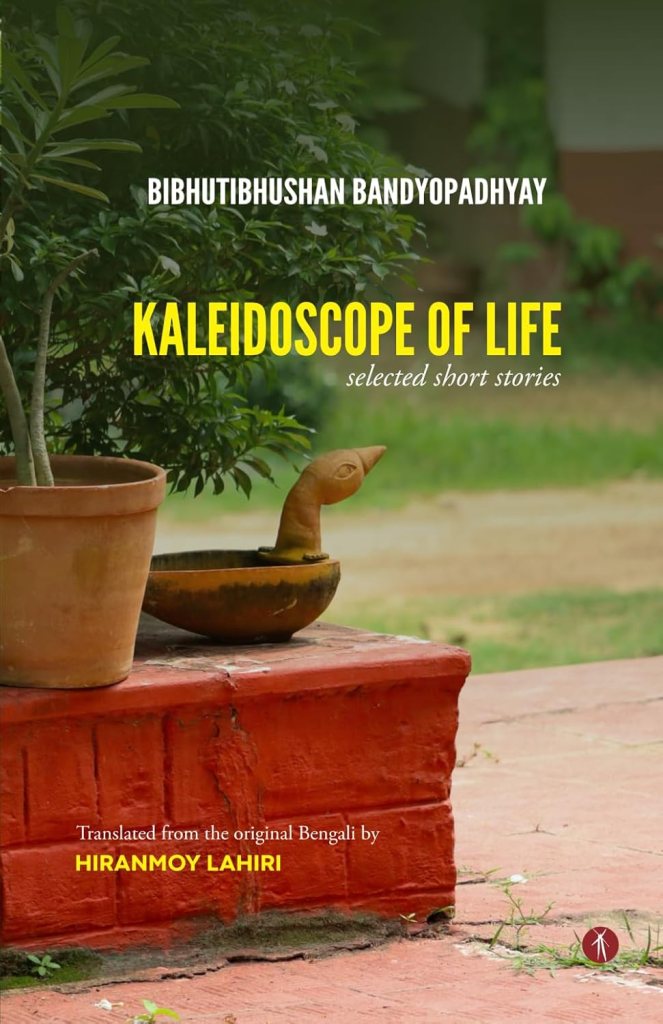

Title: Kaleidoscope of Life: Select Short Stories

Author: Bibhutibhusan Bandyopadhyay

Translated from Original Bengali by Hiranmoy Lahiri

Publisher: Hawakal Publishers

Bibhutibhusan Bandyopadhyay (1894 – 1950) is one of the best-known Bengali writers of the twentieth century and therefore needs no introduction. Though most of his works are largely set in rural Bengal, he didn’t receive much critical attention until 1928. Author of famous novels like Pather Panchali (1929), Aparajito (both of which inspired the famous film director Satyajit Ray make his films based on them), Chander Pahar and Aryanak, he is the also the author of several short story collections like Meghmallar (1931), Jonmo O Mrityu (1937), Kinnardal (1938), Talnabami (1944), Upolkhondo (1945), Kshanavangur (1945), and Asadharon (1946). The multifaceted nature of his short stories has invited translators to explore the different facets of this genre and till date, we find several new translated volumes of his short stories see the light of the day quite frequently.

An interesting feature of the short story is that down the centuries the genre’s changing variety made it difficult to be classified under any fixed notion. Whatever may be the subject matter, structure, or style, a short story tells a ‘story’; otherwise, readers would not read it. Whether events in their stages of development or sequential movements and logical relationships are enough for it to be considered a story have been debated so often that it is not necessary to repeat them here. We just need to remember that as far as the short story is concerned, readers have opted for it because of the beauty that lies within its compact structure, a beauty that thrills the reader when the story ends.

Now to come to this collection of Bibhutibhusan’s short stories selected and translated by Hironmoy Lahiri, a young translator and a freelance writer. Apart from the semi-autobiographical piece “How I began writing,” with which it begins, there are fifteen stories ranging from the sentimental, bizarre, thrilling, meditating, and occult where different other kinds of emotions are also expressed. Except for a couple of already translated pieces by other hands, most of the stories selected here by the debut translator have not been translated earlier and all of them are unique for their theme, style and narrative method. The stories have not been chosen on the criterion of chronology of their appearance in print or a particular theme which is usually resorted to by other translators; instead, the focus has been on the diverse nature of the author’s creative world. The volume thus includes ‘slices of life’ stories, unusual stories such as those of smugglers and dacoits, fictions of remote places and unusual personalities, and even supernatural narratives. They really provide a comprehensive view of Bibhutibhusan’s genius, and the phrase ‘kaleidoscope of life’ mentioned in the title definitely justifies this collection.

The very first story in this collection titled Upekshita, ‘The Disregarded’, is significant because it happens to be Bibhutibhusan’s first published story that appeared in the leading Bengali magazine Prabasi in 1921 and narrates the writer’s special relationship that he had developed with a village lady who took on the responsibility of taking care of his meals and looking after him. Drawn upon his personal experiences, especially during his stint as a teacher at a suburban school in Harinavi, when the myopic residents of the area misrepresented the author’s innocent nature of the relationship with the lady as a scandalous incident, it led to such misunderstanding that Bibhutibhusan eventually resigned from his school and moved to Calcutta.

‘Archaeology’ talks about a statue that mysteriously comes to life and establishes Bibhutibhusan’s interest in ghosts, the mystic and occult that is revealed in several other stories as well. Some of them are simplistic, like the story ‘Motion Picture’ that narrates the vision of seeing a lady djinn swinging outside an old house, or the sighting of the ghost of an opium seller in ‘Gangadhar’s Peril’. But there are also much more complicated ones like the very popular long story of ‘Taranath, the Tantrik’ where the protagonist is a mystic figure and practitioner of occult. With a growing fascination for tantra and tantric practices and philosophy in real life, it is said that the author had interactions with a commanding female ascetic who was a devoted follower of the Hindu goddess Kali, and she offered him words of wisdom about tantra and afterlife. The popularity of this fictional character created by Bibhutibhusan was later continued by his son Taradas Bandyopadhyay and even graphic stories continue to be created on him.

Bibhutibhusan’s penchant for exotic locations in his fiction like Chander Pahar (The Mountain of the Moon, 1937) and Moroner Donka Baje (The Death Knell, 1921) comes out clearly in the story ‘Chyalaram’s Adventure’ where a driver is recruited to help the King and his family escape from Kabul by crossing inhospitable terrain and reach India. The narrative is packed with action and thrilling escapades and Bibhutibhusan portrays Chyalaram’s brave actions and unorthodox approach to life in a positive light. As in the novels mentioned above, it expresses the author’s impressive ability to vividly and accurately describe exotic places he had never visited but write about them imaginatively, totally resting upon ‘the wings of poesy.’

In several stories, we find a delicate twist at the end of the tale, be it ‘Grandpa’s Tale’ narrating how he was forced to marry a dacoit’s daughter with a subtle touch of humour seamlessly integrated into the narrative, or ‘Not a Story’ that focuses on the danger posed by dacoits in rural Bengal at that time, where a traveller narrates the tale about a person called Satish Bagdi; or the sweet romantic ending of ‘The Suitcase Wrap’ that was inspired by an actual event when the author’s sister-in-law’s suitcase was accidentally switched on a train. This story captured the attention of readers and was eventually made into a very popular Bengali feature film called Baksho Bodol. ‘Jawharlal and God’ is a satirical tale born out of the author’s anguish and sorrow caused by the Partition of India and the tumultuous aftermath of World War II. The story was written to depict the loss of human values and how man had lost compassion and wonder for the natural world and distanced himself from God. Each of the remaining stories in this collection is unique and once again the translator needs to be congratulated for such an eclectic selection.

Providing a suitable glossary at the end, Hironmoy Lahiri has tried to stick to the original as far as possible, as well as to keep inconsistencies at bay. He has also taken particular care to maintain the essential Bengali linguistic and cultural nuances in the stories. The book will provide non-Bengali readers a good example of the quintessential Bibhutibhusan Bandyopadhyay, who is definitely a difficult writer to translate. The stories explore several universal themes that transcend cultural boundaries and will prove to be popular with readers from different cultural backgrounds.

.

Somdatta Mandal is a critic and translator and a Former Professor of English, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International