Visiting a museum is serious business in Japan. Suzanne Kamata visits a Museum dedicated to an American Japanese artist

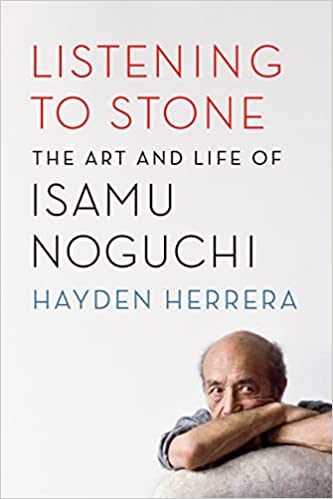

The famous American sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) lived in the town of Mure, just fifty minutes by car from my house. Now it’s the site of an outdoor museum featuring his work. Although I was interested in seeing his stone sculptures, I had never been to the museum. I’d had just read Listening to Stone, Hayden Herrera’s fabulous new biography of the artist, which had reignited my interest in his life and his work. I knew that his mother, Leonie Gilmour, was American. His father, the poet Yone Noguchi, was Japanese.

I learned that he had once posed as the Confederate General Sherman for the sculptor originally commissioned to create the Civil War monument on Stone Mountain in Georgia. Also, I read that Noguchi volunteered to teach Japanese Americans interned during World War II. He was so handsome and charming that married women in the camp fought over him. I read about how he created his famous paper lanterns. I read of his tribute to Benjamin Franklin. I also learned of his affinity for the blue stones of Shikoku.

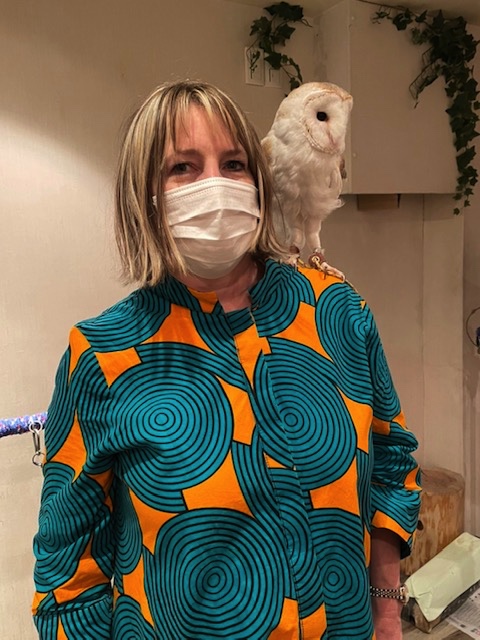

I decided that it was finally time to go to the museum. I invited my friend Wendy to go with me. She’s a college professor and a writer. Like me, she’s from the Midwest. She has also lived in Shikoku for over twenty years. Like me, she’s married to a Japanese man and has Japanese/American children. We often get together to discuss our writing, her pet goats, and other things. Wendy grew up in the town of Rolling Prairie, Indiana, which has a population of about 500 people. Coincidentally, when Isamu Noguchi was a boy, his mother sent him to an experimental boarding school in that very town. Wendy is also a fan of Noguchi. She had been to the Museum a few times before.

“I’ll ask Cathy to go with us,” she said.

Cathy is a Canadian translator who sometimes does work for the museum. She had translated a best-selling Japanese book about tidying up. This book was always popping up in my Facebook feed. The sight of this title always makes me feel as if I should be cleaning my house instead of writing books or reading Facebook updates. Housework is not my favorite thing. I had never met Cathy, but I’d heard of her. I worried that Cathy might be an extremely tidy person. She might not approve of me.

“That sounds great,” I said. “I’d love to meet Cathy.”

It takes some planning to visit the Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum Japan. For one thing, the village of Mure is not exactly a well-trodden spot. For another, the museum is only open three days a week — Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. Tours are held three times a day by appointment only. In order to make an appointment, potential visitors must write their preferred dates and times on a postcard and mail it. Email is not allowed, at least not for those living in Japan. Finally, the admission fee for adults is 2,160 yen (about $25), which is a bit pricey, as museums go. The barriers are intentional. They are meant to weed out people who are not serious about Noguchi’s art.

We made a reservation to visit on a Thursday at one p.m. Cathy suggested that we go out for udon[1] beforehand. The area is famous for its fat, doughy noodles served in broth. Cathy knew of a restaurant on a mountainside that we could reach by ropeway. I imagined slurping noodles while watching wild monkeys in the trees. We would have a leisurely lunch. Afterwards, we would admire the sculptures in the garden museum. How lovely!

The morning of our outing, a light rain was falling. I entered my destination in my cell phone’s navigation app and started the car’s engine.

“Turn right,” a woman’s calm voice said.

“Okay,” I replied, turning right.

The voice directed me onto the highway.

I drove and drove. I went past pine-covered mountains. I passed small villages nestled in valleys. The rain pattered against my windshield. A sign warned me to beware of wild boar which sometimes wandered onto the road. Off to the left, I glimpsed the Inland Sea, the tiny islands that seemed to be floating just offshore.

Although I knew that the village of Mure was only fifty minutes from my house, the voice on my app convinced me to keep going. When I was in the middle of a tunnel, far from any city, the woman’s voice said, “You have arrived at your destination.” Clearly, I was now lost.

I tried to send Wendy a message. She didn’t reply. After backtracking and driving around for another hour, I pulled over. I checked my phone. Foolishly, I had not given Cathy my phone number. Even so, she had managed to call me and gave me directions.

Time was ticking by. We wouldn’t be able to have lunch on the mountainside restaurant. We might even miss our long-awaited appointment at the museum. Why hadn’t I taken the bus? I scolded myself. Why hadn’t I studied a map? Why had I relied upon my stupid cell phone?

I got back on the road. As it turned out I was going in the wrong direction again. After another phone call, I turned around. I paid the man in the toll booth again, and drove on, finally arriving at our meeting place, a convenience store parking lot.

Wendy motioned me over to Cathy’s car. “Hurry.” She wasn’t smiling. Her voice was stern. “We are quite late.”

I climbed in the car, apologising profusely. Wendy seemed a bit angry. Who could blame her? She had arranged for me to meet the famous translator, who was probably an excellent housekeeper. Cathy had made a reservation at the exclusive museum. I was making a terrible impression.

“We’re just glad you made it,” Cathy said kindly.

“We bought these for you,” Wendy said. She tossed a couple of rice balls and a sandwich into the back seat. They had already eaten lunch while waiting in the car. Once again, I regretted missing out on our ladies’ lunch in the restaurant on the side of the mountain.

Cathy called the museum and asked if it was okay to join the tour a bit late. She was on the board of the museum. She had even interpreted at the memorial service for Noguchi when he died in 1988. If she hadn’t been with us, I’m sure I would have been denied entrance.

“I’m so sorry,” I said again.

We pulled up in front of the building which housed the reception desk and gift shop. The rain had abated. Cathy parked the car. She went to buy our tickets. Our scheduled tour had already begun. We hurried to join the others who had made a reservation in the garden. As I followed Cathy, I noticed that there were piles of rocks everywhere. Somehow the grey sky and the wet stones made the scene all the more poignantly beautiful.

First, we entered the Stone Circle sculpture space. There were many stone sculptures. Some were finished at the time of Noguchi’s death and signed with his initials, some were not. Although the sculptures had been named, they were not labeled.

We asked the guide about some of them. She told us that one tall sleek stack of blocks was made partly of stones imported from Brazil. The area has a history as a quarry. Noguchi sometimes used stones from the nearby island Shodoshima. He also sourced his materials in Italy and other far-off places. Imagine the shipping costs!

We peeked into his workspace, housed in a weathered wooden shed.

“He was very particular about his tools,” I said. I had read that in the book. Yes, here were his carving tools, carefully aligned. They were just as they had been when Noguchi was alive.

“Yes, he was,” Cathy agreed, raising her eyebrow.

“Oh, and here is the model for his slide!” I recognised an image from the book I had just read. It was a white spiral, resembling a seashell. Noguchi believed that art should be part of daily life. He thought that art was for everyone, including children. He designed several playgrounds. Not all were constructed. This slide had been exhibited at the Whitney Biennial, one of the most prestigious art shows in the world.

We took a meditative stroll among the arranged rocks. Next, we climbed stone slab steps to a sculpted garden enclosed by a grove of bamboo trees. The space featured small grassy hills and a moon-viewing platform.

“I read that his ashes are in one of the stones here,” I said.

“Yes,” Cathy said, surprised at my font of Noguchi knowledge. “Up at the top of the hill. Shall we go pay our respects?”

As we climbed, Cathy explained how this space had been sculpted. Stones had been arranged to mimic the islands visible in the distance. Noguchi had been furious when someone had built a house higher up the mountain. Although it wasn’t on Noguchi’s property, it spoiled the view. Thus, it spoiled the work of art which was the garden. Traditional Japanese gardens often make use of “borrowed scenery.” Eventually, the house was bought by the museum’s caretaker and destroyed. Now, the view is as Noguchi intended it to be.

We paused for a moment before the giant egg-shaped rock at the top of the hill which had been cut in half. After Noguchi was cremated, some of his ashes were encased in the stone, and the stone was reassembled.

Next, we had a look at the house where he lived in the last years of his life. Inside, a paper lantern which resembled a jellyfish hung from the ceiling. The floors were made of straw mats. I knew from reading his biography that he had lived here with a Japanese woman who was married to a friend of his. Noguchi couldn’t speak much Japanese, and the woman couldn’t speak English. Even so, they were lovers. I imagined them sitting on the verandah, gazing out at the sculptures. Maybe they sat there sipping tea in silence. I thought of mentioning the lover to my companions, but I decided that it was too gossipy. I didn’t want them to think that I wasn’t serious about his art.

Afterwards, we decided to go to a café near Cathy’s house. We drank coffee and ate mango cheesecake. It occurred to me that my frustration from earlier that morning had disappeared. Wendy no longer seemed stressed and angry with me. Being in that beautiful, natural garden had made us all feel calm.

I was sure that I would be able to find my way back home.

[1] Thick noodle made of wheat, Japanese Cuisine.

Suzanne Kamata was born and raised in Grand Haven, Michigan. She now lives in Japan with her husband and two children. Her short stories, essays, articles and book reviews have appeared in over 100 publications. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize five times, and received a Special Mention in 2006. She is also a two-time winner of the All Nippon Airways/Wingspan Fiction Contest, winner of the Paris Book Festival, and winner of a SCBWI Magazine Merit Award.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL