By Paul Mirabile

Tommy ordered a second pint of beer at the counter. The bar buzzed with the usual crowd, and a few groups of tourists, mostly from northern Europe, were beering it up as they did at home. Tommy had had a long day preparing breakfast and clearing the rooms at the Hotel Van Acker, Jan Willem Brouwersstraat, 14. Afterwards, he accompanied three Spanish tourists to the ‘high’ spots of Amsterdam: Anne Frank’s house, Vondel Park, the Rijks and Stedelijk museums, Rembrandthuis, Madame Tussauds, completing his tour at the ‘hot’ spot for all such tourists — the red light district. There he left the Spaniards, tired of having dragged them about the town while straining to understand their Spanish.

How long had he been at it ? Four … five years ? Who knows. Something in his mind had snapped. Oftentimes he suffered from bouts of amnesia or blackouts, a succession of synapse that triggered in him extreme panic, even paranoia. He felt an elbow nudge him lightly in the ribs: “ All right, mate?” asked a middle-aged man with long, blond, silken hair and ultramarine blue eyes.

Tommy eyed the man suspiciously. He had managed to squeeze himself in at the counter as imperceptibly as a ghost. “Yes, I’m all right. Why?”

“Oh, I just saw you staring into space as if you were in great thought or pain.” Tommy smiled leerily.

“No pain, just thinking small thoughts.” The other smiled. His teeth were very white. He reached over, took a few pinches of tobacco from a drinker’s pouch with unabashed effrontery and rolled himself a cigarette.

“Do you do that often?” Tommy enquired lamely.

“What?” the other asked puffing away dreamily.

“Pinch tobacco from people’s pouches.”

“Of course I do, it’s been my custom for ages,” answered the tobacco pincher with a whimsical gleam in his eyes. “What are you doing in Amsterdam, working I suppose?”

Tommy straightened up. “I work at the Hotel Van Acker doing odd jobs for the owner.”

“Ah, yes, Van Acker … Where they found that murdered dwarf.”

“He wasn’t murdered. He died of a heart attack.”

“The police never found the key to his room. That is strange. To die of a heart attack in a hotel room without the key.”

“So what?”

“Sounds a bit shadowy to me. But that’s all in the past. And who cares anyway, right ? What’s your name?”

“Tommy.”

“From?”

Tommy hesitated: “From Luton.”

“Luton?”

“It’s in Bedsfordshire.”

The pincher of tobacco nodded, rolling himself another cigarette. “I’ve seen you handing out leaflets or pamphlets in the streets.”

“That’s possible.”

“How’s the salary at Van Acker’s?”

“I get on. Van Acker gives me my meals and I sleep in the cellar room under the stairway.”

There was a very long silence — a silence so long that Tommy began to grow nervous. Finally, the man said: “Listen, I might have a job for you Tommy that will earn you enough money to live like a prince anywhere in the world for the rest of your life. One night ! Only one night, and you’ll become as rich as Crassus.”

“Who’s Crassus?” asked Tommy mistrustfully. The other laughed.

“The richest man in the Roman Empire. You see, my proposition deals with paintings; I’m an art collector.”

“Pictures? I like pictures. I take all my hotel tourists to the art museums.”

“Perfect. Here’s my address. Come by any time after eight at night. By the way, my name is Gustav.”

“Gustav … Gustav what?”

“Gustav Beekhot. I hope to see you soon, Tommy. Tot ziens[1]!” Gustav slapped Tommy on the shoulder and left the crowded bar, weaving through the mass of throbbing, bulky bodies like a shadow amidst a darkening, nameless stretch of land …

Five days later, after having wrestled with his thoughts, Tommy leaned his bicycle at the gate of a plank which led to Gustav’s house-boat on the Ruysdaelkade Canal. It was quite an impressive barge. He knocked at the door. Gustav, eyes a watery blue, opened the door and wished his visitor a hearty welcome ‘aboard’. “Just in time for dinner,” he said flippantly. When Tommy stepped in he couldn’t believe his eyes: they swept over a long ‘hold’ full of paintings of all sizes and colours, some hanging off the walls, others on easels, and still others scattered on the uncarpeted ‘bottom deck’, unfinished.

“You might open a museum here,” he suggested, strolling from painting to painting. “I like to look at pictures. When I accompany people to the Rijks or to the Rembrandthuis I always take my time to examine the pictures. The tourists just look at the title and at the name of the painter.”

“Yes, very few people really examine a painting.” Gustav placed two bowls of rice, shredded carrots and two pints of Heineken beer on a hackney table. “I for one prefer to paint them, buy or sell them, although I do often go to the museums for inspiration.”

“You sell your own pictures, then?” Gustav chuckled.

He gave Tommy a conspiratorial wink: “No, who would ever buy a Gustav Beekhot ? To tell you the truth I sell the ones I steal or have stolen from museums or from private collectors.” Tommy, who had sat down at the table dropped his fork. He stared at Gustav in disbelief. All that had been said with absolute aplomb. “Yes, Tommy my lad, sometimes I do buy them from contemporary Scandinavian painters living in poverty, but I prefer to steal them … It’s cheaper!”

“But … but how can you steal a picture from a museum?” questioned Tommy in alarm.

“It’s quite simple. It’s a question of know-how. Thievery is an art, my dear lad. And if you are willing, you will learn this art easily, and by doing so, earn a half a million dollars!”

Tommy jumped up. “No, please, let us eat, and I shall spell out all the niceties to you. There’s really nothing to it: a wiry, loose-limbed body like yours, will-power and the common sense to keep your mouth shut. And I do believe you possess all those aforesaid qualities. Am I correct?” Tommy remained voiceless. “Of course you possess them. But you doubt my word. Others too doubted, and today are living like kings in Tahiti, the Seychelles or in some Central American country.”

“A half a million dollars?” Tommy managed to stammer, sitting down slowly as Gustav glided between his paintings in a breezy, phantasmal gait to procure a bottle of Jenever in his kitchenette at the ‘prow’.

“Yes, Tommy. One night. One night only.” Tommy peered out the ‘porthole’, it had begun to drizzle. He watched as the drops gently fell upon the unruffled canal waters; they fell gently, rocking his host’s barge dreamily. He suddenly felt a seizure coming on. He strained to control it, the house-boat rocking … rocking so gently, like the drops of drizzle. Something snapped in his head; he shook it out. Gustav ate his rice and carrots as if he noticed nothing of the crisis that his visitor, and future accomplice, was suffering. He was smiling that engaging smile.

“What do I have to do?” came Tommy’s belated reply in spite of himself. He had asked that without being fully conscious of actually asking it.

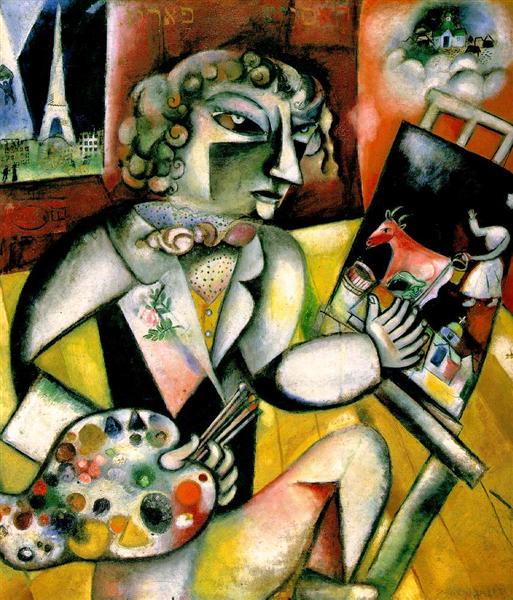

Gustav stopped eating, sized him up, then thrust his taunt face forward. It had a ghostly white appearance to it: “Crawl through a very very narrow tunnel about two hundred metres long behind the Zadelhoff Café to the storage room of the Stedelijk museum. In that storage room you will find a painting by Marc Chagall, A Self-Portrait with Seven Fingers, which will be waiting for you to cut out of its frame with a razor blade. The nightwatchman has already put the painting exactly where you will pop up from the storage room hole.”

Gustav stood, went to a broken, plastic shelf over his wash-basin and picked up a razor-blade. “Look, this is how it should be done.” And the art dealer began to cut out a painting from its frame. Tommy gasped. The other laughed. “Don’t worry, it’s one of my worst chefs-d’oeuvre …” Gustave then rolled up the canvas and placed it into a plastic cylinder. “There you have it my boy,” he beamed. “Sling the cylinder over your shoulder, drop down into the hole and crawl back through the tunnel where I shall be waiting for you.”

“But this tunnel … I can’t see …” Gustav put up a hand.

“The tunnel was dug during the second world war and used either to store ammunition by the local militia or as an escape route for Jews and communists.”

“How do you know all this?” Tommy asked incredulously.

“I studied history, and have many friends who deal in these particular matters.” There was a shrewd, impish twinkle in his host’s eyes.

Tommy seemed a bit sceptical about the whole operation. Gustav’s eyes were all alit, the glow of which stabbed at his distrustful heart. Gustav noted his guest’s wavering emotions. “My buyer will be in Amsterdam in five days,” he proceeded in a haunting undertone. “He’s arriving from Tampa, Florida and will be paying me one million three hundred thousand dollars for the painting. You will receive five-hundred thousand.”

He went to a drawer. “Here, this bank card will permit you to withdraw your share of the profits in any bank machine in the world. It’s a Swiss Banker’s card. But under no circumstances must you withdraw more than two thousand a day; bank administrators may become suspicious.”

“Where’s my bank?”

“That I cannot tell you,” Gustav answered sharply. “I suspect that you are mistrustful of me?” he chaffed.

“No, I’m not, but still …”

“No buts. The card is perfectly valid once the money has been deposited. And it will be after your mission has been completed. But I warn you Tommy, you must leave Amsterdam immediately before the museum authorities realise that the Chagall has been stolen. My buyer will leave on a morning flight back to Florida.”

At that moment Gustav poured out two glasses of Jenever, raised his and cried — ‘Godverdomme’ [2]! And with that coarse shout they both gulped down the divine nectar. Tommy felt a mounting tension in his chest, throat and jaw. Had he made a pact with a man whom he hardly knew ? He left at midnight, benumbed, as if he were a bit tight.

For two days Tommy struggled to control his taut emotions. To weigh the consequences of this incredible proposition. He could become immensely rich after a few hours of mental and physical toil, yet something irked him. It all seemed so unreal! He walked the streets of Amsterdam in the late afternoons, flicking matches into the air one after the other, watching the lit sticks glide gently to the street where the last lingering sparks sizzled out. He repeated aloud, “Tahiti, the Seychelles … I wonder where they are?” over and over again. He would take out the bank card and study it carefully. “It looks real to me,” he assured himself, albeit nervously.

On the fourth afternoon they met for tea at the Zadelhoff Café, after which Gustav took Tommy behind the café and showed him the sewer lid which led to the tunnel. Then they strolled over to the Stedelijk Museum, and whilst promenading through the halls of paintings Gustave cautiously pointed out the storage room where the Chagall had been stored for a future exhibition at another museum. All that day Tommy had admired the art collector’s professionalism and precision in elucidating the details of this very risky, but lucrative operation.

“Will-power, nerve and stamina, my lad,” Gustav kept repeating until he told Tommy to meet him that very night behind the Zadelhoff Café at one o’clock sharp. The buyer had booked a morning flight back to Florida. “One night ! Only one night, my friend. Don’t let us down … “ Tommy clenched his fists. He suddenly felt a surge of unwonted force, a force he had experienced many years ago before his unexpected arrival in Amsterdam. Gustav slapped him on the shoulder and glided away like a phantom in the reddening twilight …

A far away church-tower bell struck the hour of one. And so it happened, happened like a dream …

Gustav cut a spectral figure outlined against an ill-lit, moonless night as he waited impatiently for his accomplice. At that moment Tommy arrived, a trifle late. They both set immediately to work to open the heavy sewer lid. Once pried open, Tommy climbed down the rusty rungs, a torch in hand, the plastic cylinder slung over his shoulder. “The rats! The rats!” he called, looking up, his lithe body trembling.

“Rats ? The rats will scramble away when you train your torch-light on them,” Gustav shouted down in a weird, stilted voice. “Don’t talk nonsense ; just move on …”

And he slid the sewer lid over the hole. Tommy stopped. Darkness engulfed him. The boy panicked. — All alone! All alone! — he lisped to himself in fear. He nevertheless carried on down into the damp darkness training the light along the broken stone walls dripping with age. There, the opening of the tunnel! It was true. There was the tunnel … But so narrow … so terribly narrow …

Poor Tommy was hardly able to push himself into the opening. He began to cry. He felt he had been buried alive in a toolless coffin. All alone! All alone! “Mummy!” escaped from his dry, chapped lips. Yet Tommy crawled on and on. The thought of a half million dollars flooded his inflamed brain. The brave boy elbowed a painstaking trail over root and rock, his torch-light cutting out a thin stream of blissful light that disappeared into a dark Nothingness. A Nothingness that frightened him, reminded him of vague scenes in some other life that he had once led, a former life of battling and crying out in a moonless, raging darkness …

His head struck stone. Yes, it was stone! The gallant Tommy had reached the museum storage hole. He straightened up with difficulty, touched the cold walls; a ladder had been provided for the Second World War escapees.

“The rest will be child’s play,” he whispered in an echoless vacuum. Up he clambered excitedly. The hole seemed endlessly deep. Was that possible ? Ah, the floor tile … Finally. He pushed it open as easy as that. “Child’s play,” he sniggered as if speaking to Gustav.

Tommy pulled himself out into a deep, deep darkness. A darkness he had never experienced before. He searched for the razor-blade in his trouser pocket, trained his torch …

A merciless neon light suddenly blinded him, absorbing all the darkness, save that which still lay heavy and hauntingly in his head. Four policemen stood pointing at him, laughing and laughing. A very stoutish, well-dressed man stepped out from the policemen and grabbed the boy by the scruff of the neck. “So this is the little twit that has been hiding out like a rat!” the man chidded in broken English. “Hiding in the storage pit, hey? Think you’d slip away from us? What on earth are you doing in here you scamp, playing hide and seek?” Tommy said nothing. Baffled, he had lost all contact with reality. “Deaf and dumb, hey? Let’s see.” One of the police officers struck the boy across the face.

“Please don’t,” he whimpered.

“There you are, he can speak after all, and with a British accent, too,” pursued the well-dressed man who happened to be the museum director. “So, why are you hiding here ? What are you doing in that pit? Look at the mess you’ve made.” Indeed, the storage hole was filled with empty cracker and potato chip bags that Tommy had been eating. “Were you drinking water from the lavatory tap ? Look at this floor, there’s water all over it.” He poked Tommy in the chest.

“I was sent to steal a picture … Marc Chagall …”

“Steal a painting ? A Marc Chagall ? How were you to get it out of the museum ? Are you masquerading as Honest Jack[3] ?” This was asked with biting irony.

“Through the tunnel back to the Zadelhoff café.”

“Oh, I see … a tunnel to the Zadelhoff café.” He turned to the policemen: “Is there a tunnel to the Zadelhoff café.” All the policemen laughed and laughed, pointing at the sulking boy whose filthy, ill-smelling clothes struck a grotesque contrast with the museum director’s well-tailored suit.

“And with a razor-blade cut it out of its frame,” Tommy hurriedly added.

“Where’s the razor-blade?” one of the policemen demanded, taking him by the arm. “Give it to me.” Tommy searched his pockets. He held out a safety-pin.

“No tunnel, no razor-blade,” broke in the museum director. “You’re either a liar or a raving lunatic.”

“But I crawled through it. Gustav Beekhof showed me the tunnel and told me to steal the picture when he invited me to his house-boat,” Tommy pleaded, tears flowing over the dark shadows of his wild, tired eyes.

“There is no tunnel you little liar!” screamed a policeman. “And who is this Gustav Beekhot? Where is his house-boat?”

Tommy racked his brains: “I don’t know the exact address but I can take you there.”

He was hustled out of the museum into the moonless night, bundled into a police van and off they sped through, along and over streets, canals and bridges … until …

“There, on the Ruysdaelkade Canal,” the boy shouted in triumph. “His house-boat is the second …” Tommy stared in horror: there was no house-boat ! A police officer pulled him out of the van and dragged him to the slip where the house-boat should have been docked. Tommy rubbed his red, stinging eyes : “But it was there … I …”

“Shut-up you impudent little runt!” the officer barked. “I’ll check.” He returned to the van.

A few minutes later, he returned. “There’s no house-boat registered in that slip, and we have no record of a Gustav Beekhof,” he stated stiffly, looking hard at Tommy. “You’re raving mad.” A bewildered Tommy stepped back, his thoughts running riot.

“No house-boat. No Gustav Beekhof,” fumed the police officer. “A little scamp of a thief, that’s what you are.” And he twisted Tommy’s ear until it turned beet-red. “What’s your name, boy?”

“My name ? My name is Outis,” he lisped, holding his smarting ear.

“And your papers?”

“Papers ? I have no papers … I’m …”

“Shut-up!” the police officer stormed, turning red. He took Tommy by the shoulders and shook him so hard that his teeth chattered. All of a sudden something snapped in his brain. The boy was seized by a mounting tension which sent him spiralling into a dark nothingness that he had never before experienced — a nothingness where he drifted through a darkened, nameless stretch of land …

DOCTOR VAN DIJK’S REPORT

The patient who calls himself Outis, as recorded by the police, most probably English-born, was found hiding in the Stedelijk museum storage room for two days with, according to the patient, the intention of stealing Marc Chagall’s ‘A Self-Portrait with Seven Fingers‘, which the aforesaid patient claimed had been deposited in the room for that purpose. This claim was disclaimed by the museum director, Mister Aalbers who avowed that the painting hangs in its usual place in the museum. The patient being questioned by the police, maintained that he was put up to the supposed theft by a certain Gustav Beekhof who apparently does not exist, according to police records, nor does his place of residence: a house-boat on the Ruysdaelkade Canal. The patient was promised a half a million dollars for the theft, which, as he declared, was undertaken by crawling through a tunnel from behind the Zadelhoff Café to the museum storage room. The police confirm that this tunnel has never existed. Furthermore, when the patient showed the police his bank card with which he was to withdraw his share of the theft, it turned out to be a library card whose owner’s name and library location had been thoroughly effaced beyond deciphering.

The patient has fallen into a coma for several days now. There seems to be no doubt that he is suffering from an acute case of schizophrenia, caused perhaps by a sudden mental or physical traumatism that has created an imaginary parallel world through which the patient wanders in and out whenever jolted by an unsual event or encounter.

The patient thus will remain in our clinic under strict observation until he emerges from his unconscious state.

Chief Psychologist of the Psychotherapierpraktijk Overtoom

Wilfrid Van Dijk, May 9th, 1975

.

[1] ‘Good bye’ in Dutch.

[2] ‘God damn it’ in Dutch. A rather ‘informal’ interjection when making a toast amongst close friends.

[3] The notorious English robber John Jack (1702-1724). He was hanged for his daring thefts.

.

Paul Mirabile is a retired professor of philology now living in France. He has published mostly academic works centred on philology, history, pedagogy and religion. He has also published stories of his travels throughout Asia, where he spent thirty years.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International