Book review by Meenakshi Malhotra

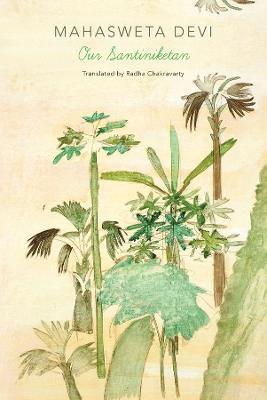

Title: Mahasweta Devi, Our Santiniketan

Translator: Radha Chakravarty

Publisher: Seagull

Mahasweta Devi’s reminiscences about Santiniketan, where she spent some of her formative years, between early 1936 and the end of 1938, (almost three years between the ages of 10 and 13), is a beautifully written and luminous tribute to this unique educational institution.

The place, people, flora, fauna, educational method and curriculum (through co-curricular activities), the people it housed and the ideas it nurtured are described by Mahashweta Devi in loving detail, with great skill and observation. What makes these reminiscences even more remarkable is that the book Amader Santiniketan is based on memories of events which transpired almost sixty-four years before the book finally came to be written. A richly flavoured chiaroscuro of events, ideas and people all woven into the fabric of memory, Mahashweta compares her memories to a feather. “Like a dazzling feather that has floated down from some unknown place, how long will the weather keep its colours, waiting? The feather stands for memories of childhood. Memories don’t wait. Memories grow tired. They want to go to sleep”

Describing a life lived in the lap of nature, the book depicts the beginnings of her growing closeness with the natural environment and the eco-system it fostered before the depredations caused by man’s excessive needs and greed. Thus, she writes, “Santiniketan taught us to respect nature, and to love it.” Using two frames — of a dimly remembered past time steeped in nostalgia and a disturbing present — she voices her sense of disillusionment: “Now with each passing day, I see how humans destroy everything. Through the agency of humans, so many species of trees, vines, shrubs and grasses have vanished from the face of the earth-so many species of forest life! Aquatic creatures and fish, so many species of birds, have become extinct, lost forever.” Further, a great calamity has befallen the natural world and while science and technology have advanced, the “balance of nature can never be restored.”

The author’s sensitivity to and observation of animals is perhaps unusual and also prescient in its engagement. Thus, she recalls how she long harboured a “profound tenderness” towards donkeys. Her thinking seems to almost anticipate a trend in thinking that has increasingly been identified as post humanistic.

The translation captures the iridescent quality of the writing irradiated by flashes of memory as the ageing author is often assailed by amnesia. Thus, she writes, “I have travelled a long distance away from my childhood” and that her memories are losing their colour and their sheen.

A book by a trailblazing activist writer like Mahasweta Devi writing about Santiniketan, a unique educational experiment nurtured and fostered by Tagore, who was a world-famous poet and Asia’s first Nobel laureate, is a literary treat of a special kind.

Tagore was so prolific that it could be said of him, that not only was he great but also that he was the cause of greatness in others. Santiniketan was the privileged space which witnessed a cultural efflorescence, the full flowering of the 19th century Bengal Renaissance that started more than half a century before. Thus, it was a site where the creative arts, literature, painting, sculpture, music and dance flourished. The institution attracted new talent to itself, both from India and beyond. About the educational methods of Santiniketan, Mahasweta writes: “In Rabindranath’s time, Santiniketan offered independence and nurture.” And “those days, they did not teach us the value of discipline through any kind of preaching. They taught us through our everyday existence.” Precepts and ideals were instilled subliminally, “they (instructors in Santiniketan) would plant in our minds the seeds of great philosophical ideals, like trees.” She also adds that Aldous Huxley felt that Rabindranath’s major legacy lay in his thoughts on child education. The educational curriculum that was practised in Santiniketan taught students not just to know things, but to love nature and the universe. A vital question that she poses is: why does education in love not figure in today’s curriculum?

Time and again, Mahasweta bemoans the fact that the outlook and attitude towards education that is in evidence these days has entirely missed the point and the essence of Tagore’s teachings that were manifested and actualised in Santiniketan. This is not just nostalgia but a clear-eyed recognition of the quality of nurture — both physical and intellectual– offered by Santiniketan. It offered a wonderfully varied work schedule. It trained their vision and offered the valuable lesson that no activity is worthless.

At the center of her narrative is of course that colossus among men, the towering figure of Rabindranath Tagore, poet extraordinaire and visionary, carrying out a unique educational and pedagogical experiment. The author feels inadequate and unable to measure his greatness. She also describes with particular poignancy the eco-system devised by him which nurtured, honed and showcased the talents of others. Many luminaries figure in the book. Some hover in the margins of the texts -characters /personages whose achievements merit a narrative of their own. So whether it is the artists Kinkar (Ramkinkar Baij) and Nandalal Bose, singers like Mohor (Kanika Bandopadhayay) and Suchitra (Suchitra Mitra),a leader and nationalist like Sarala Debi Choudhurani, a writer like Rani Chanda and a dancer like Mrinalini Swaminathan (later Sarabhai)—Amader Santiniketan takes us through a veritable hall of fame.

The book is also interesting in the glimpses it affords into the formative influences of an important writer, Mahasweta Devi herself. Her writings constitute a unique blend of narrative and activism, theory and praxis and marks a strong sympathy with the dispossessed. She writes of tribal cultures with a strong conviction of their relationship with the land. In the Imaginary Maps (1995, short stories translated by Gayatri Spivak), Mahashweta Devi bemoans a lost civilisation:

“Oh ancient civilisations, the foundation and ground of the civilisation of India……A continent! We destroyed it undiscovered , as we are destroying the primordial forest, water, living beings, the human.”

There is a self-revelatory aspect to the narrative. Even as her reminiscences conjure up a glowing image of Santiniketan as an idyllic haven in a bygone era, there is a poignancy in the book’s dedication to Bappa, her son Nabarun Bhattacharya, when she writes “I gift you the most carefree days of my own childhood, let my childhood remain in your keeping.” Mahasweta’s son was estranged from her, since she left her husband and his father Bijan Bhattacharya, when Nabarun was presumably thirteen.

Radha Chakravarty is a fairly renowned translator with a vast repertoire of experience. She has translated many writings both by Rabindranath Tagore and Mahasweta Devi. That she has previously worked on Mahasweta Devi’s writing, adds to the nuanced quality of her translation and observations. Beautifully and sensitively translated by Chakravarty and produced/brought out by Seagull, the book is a collector’s delight.

While the book is not an autobiography in the traditional sense, it weaves together fact and affect, “a fragmented whimsical mode of narration” punctuated with digression and asides. A mixture of hazily remembered facts and sharp recollections, it is peppered by flashes of the author’s indomitable spirit. In the words of the translator, “Mahasweta Devi’s text draws us in what she tells, yet baffles us with what it withholds or reinvents, teasing us with its silences uncertainties and incompleteness.” Further, “vividly present to our imagination, yet beyond the reach of our lived reality, a remembered Santiniketan hovers in the pages of the book, just like the dazzling but elusive feather inside the locked up treasure box of Mahasweta’s memory.”

.

Dr Meenakshi Malhotra is Associate Professor of English Literature at Hansraj College, University of Delhi, and has been involved in teaching and curriculum development in several universities. She has edited two books on Women and Lifewriting, Representing the Self and Claiming the I, in addition to numerous published articles on gender, literature and feminist theory.

.

Click here to read a book excerpt of Mahasweta Devi, Our Santiniketan

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL