Book review by Gracy Samjetsabam

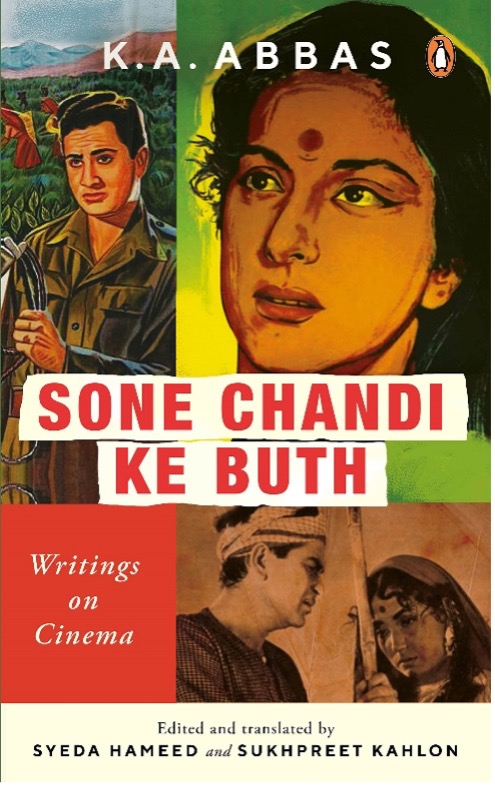

Title: Sone Chandi Ke Buth: Writings on Cinema

Author: K. A. Abbas

Editors and Translators: Syeda Hameed and Sukhpreet Kahlon

Publisher: Penguin Vintage

Khwaja Ahmed Abbas’s[1] Sone Chandi Ke Buth:[2]Writings on Cinema (2022), edited and translated by Syed Hameed and Sukhpreet Kahlon is truly, “an insider’s view of the ‘Sitaron Ki Duniya’[3]”.

The book is a constellation of Bollywood stories about moviemaking, film personalities, incidents, and fateful moments straight from the horse’s mouth. The book is divided into four sections – Funn Aur Funkaar[4], Kahaaniyaan[5], Articles, and Bombay Chronicle Articles. Abbas was often addressed as the “Human Dynamo” by his closest friends for his spontaneity and dexterity in churning out forms of expression such as short stories, novels, dramas, and films, which manifested whenever he pronounced, “Mujhe Kuch Kehna Hai”[6]. He embodies a different time and sensibility, making the man and his work a treasure from the bygone days. Professor and scholar Ira Bhaskar aptly describes, “K. A. Abbas represents a crucial figure of the Indian modern who believed that critics and artists had a responsibility towards society.”

K.A. Abbas, who was adept in Urdu, Hindi and English made the most of his multilingual skills to contribute thousands of articles on popular media including the longest-running weekly column, 46 years as a contributor in Blitz, writing for the Bombay Chronicle, 40 movies, short stories, and 74 books in 73 years. Sone Chandi ke Buth (2022) is Abbas’s last book on filmi duniya, the world of movies. The book throws a glimpse into Abbas’s journey from the young and aspiring journalist who wrote paltry salaried publicity blurbs to a scriptwriter, filmmaker and film critic of great repute who made a tradition of his own offering “love” for the art and to everyone who lovingly called him “KAA”. Bollywood’s Big B, the Mahanayak[7], the megastar fondly admires Abbas’s “unrelenting spirit” and recalls, “K. A. Abbas gave me my first film, Saat Hindustani. I call him Mamujan.”

Syeda Hameed and Sukhpreet Kahlon labelled Sone Chandi ke Buth (2022) as “adhbudh[8]”, for the book is a testimony of the contribution of the man and his craftmanship. Coming from a family of poets and writers, Abbas walked along with the stars of the industries in its golden and the silver eras and yet was a man who could make jokes of himself, give sincere criticism on the quality of an artist’s work or the movie, speak of Bollywood as a unifying factor of pluralism in India, and suggest the importance of understanding truth for a greater cause. Intelligently and humorously, the book opens a window to fascinating instances and anecdotes of his life experiences and his encounters with the people who made history in the world of movies in India via Bollywood that were crucial to the industry or the personalities. With each turn of the pages, the narrative unravels interesting stories and junctures like how in writing about V Shantaram, whom he calls “Sadabahar” or evergreen, he goes on to describe his “crashing” into the world of film and becoming a film critic through film publicity, how his editor’s advice at the Bombay Chronicle opened his wings of liberty to be critical but to do it prudently.

Drawing a fine veil between the reel life and the real life of the people with whom he manoeuvred in the film industry, the book “revealed more than concealed” the human aspects of greatness and flaws of each amidst their roles as heroes, villains or side characters in the movies. The book is filled with incredible stories of towering Bollywood personalities through Abbas’s eyes. Revelations in the section “Funn and Funkaar” captivatingly describe why he referred to V Shantaram as “The Evergreen Filmmaker”, Prithviraj Kapoor as “The Shahenshah[9]”, Raj Kapoor as “An extraordinary Karmayogi[10]”, Dilip Kumar as “Loss of a national treasure”, Meena Kumari as “The Muse of Ghazals”, Balraj Shani as “The People’s Artist”, Amitabh Bachchan as “Himmatwala[11]”, Sahir Ludhianvi as “The Lover and the Beloved”, Rajinder Singh Bedi as “The Guru”, and Satyajit Ray as “Mahapurush[12]”. The section “Kahaaniyan” sheds light on the ironies of the glamour and glitz in the film industry and on special days on the movie sets.

The section on “Articles” presents his thoughts on the relationship of filmmaking with business and its impact on society. Each article is a critical discussion of aspects of a good film, and he strongly opposes scripts that succumb to commercial sensibilities and powerfully voices the need for for “a good story” that “lies at the heart of a good film”. The section “Bombay Chronicles articles” compiles some of the finest articles of his passionate and flourishing days at the Bombay Chronicle in the 1930s as a film journalist. The articles in the concluding section continue to bring forth memorable facets of the world of films in India of the man and his times, and at the same time keep the spirit of enquiry burning in all movie enthusiasts and scholars to reflect on how much has changed over the years. Sone Chandi ke Buth brings into play Abbas, the man, the artiste and his style to showcase what a perfect blend of the head and the heart can do in film making.

If you are looking for a must-have book on Bollywood, filmmaking and movie criticism, then Sone Chandi ke Buth offers you an ample amount of it and more. Timeless memories of photos of the movies: Awara[13] (1951), written by him; Anhonee[14] (1952), a film he made on Nargis’s request; Rahi[15] (1953), a movie based on Mulk Raj Anand’s Two Leaves and a Bud starring Dev Anand and Nalini and Jaywant; Munna (1954), the first songless film of Indian cinema under the Naya Sansar banner; Pardesi [16](1957), the first Indo-Soviet production in a collaborative work of the Naya Sansar banner and Mosfilm Studio; Char Dil Char Rahein [17](1959), Abbas’s first multi-starrer movie; Chaar Shehar Ek Kahani[18] (1968), Abbas’s best-known political documentary; Saat Hindustani [19](1969), a movie on comradeship; and also, personal photos of Abbas’s self, with his family and on film sets, enhances the aesthetic of the book.

The book has a phenomenally exciting set of stories about the famous and the lesser known faces of the movie industry in India, as people with ordinary life and circumstances amid their successes and failures. The translators and editors — his niece, Padmashri Syeda Hameed, an activist, educationist, writer and a former member of the Planning Commission of India, and Sukhpreet Kahlon, a researcher on cinema studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University — need to be thanked for collating these wonderful writings that touch our hearts while forging new bonds and links through the medium of films.

[1] Indian Film Director, 1914-1987

[2] Translates to: Statues of Gold and Silver

[3] World of stars

[4] Fun and Fun makers

[5] Stories

[6] I have to say something

[7] The great actor, refers to Amitabh Bachchan

[8] Amazing

[9] The Emperor

[10] A person who believes the ultimate panacea lies in devotion to work

[11] Courageous

[12] Superman

[13] The Vagabond

[14] The Untoward

[15] Traveler

[16] Foreigner

[17] Four Hearts, Four Paths

[18] Four towns, One story

[19] Seven Hindustanis

.

Gracy Samjetsabam is a freelance writer and copy editor. Her interest is in Indian English Writings, Comparative Literature, Gender Studies, Culture Studies, and World Literature.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles