Exploring the writings of Nabendu Ghosh, his daughter Ratnottama Sengupta shares his life and times and her own journey as a senior journalist, writer and, more recently, a filmmaker.

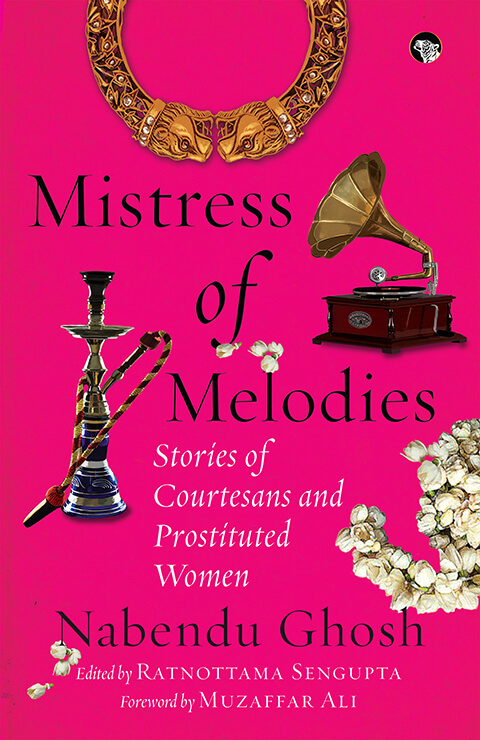

Mistress of Melodies is a new book, a translation of Nabendu Ghosh’s stories. Ghosh was an eminent Bengali writer and also a major screenwriter from Bollywood, the award-winning director of the iconic Trishagni (The Sandstorm, 1988). This collection edited by his daughter, a senior journalist, translator and writer, Ratnottama Sengupta, brings out the plight of women ranging from the glamorous Gauhar Jaan to the hapless prostitutes and widows — like Fatima who almost gets pushed into the flesh trade for feeding her hungry child. The story on Gauhar Jaan was written originally in English by Nabendu himself. The man did an excellent job in English too though he wrote in Bengali and Hindi mostly. His writing has cinematic clarity.

In 2018, another collection of his short stories That Bird called Happiness was brought out by Sengupta, who with multiple books under her belt, retired as the arts editor of The Times of India and now she is helping the world uncover the richness of the literary lore of Nabendu Ghosh. In this exclusive, she tells us more.

You are the daughter of a very loved writer, screen writer and filmmaker from Bengal, Nabendu Ghosh, along with being an award-winning journalist and film maker. How much did your father influence your choice of career? What impact did his work have on your childhood?

My father did not at all influence my choice of career as a journalist. As a matter of fact, he believed that journalism was literature in hurry. He was happy that his daughter’s name – byline — was appearing every week, often more than once a week, and across India with enviable regularity. But he would often remind me that, in pursuit of this “short-lived glory”, I was neglecting my potentials as a ‘literary writer’ which, he felt, I had in me…

But let me tell you: I would not be what I am today – an editor, translator, curator and director in addition to being a journalist – if I were not born with Nabendu and Kanaklata as my father and mother. Here’s the Why of this statement.

I must have been five or less when I developed the habit of looking attentively at visual images even before I could discern the alphabets. For, even as a baby I would leaf through the books that were everywhere in our house – in the bookshelves, on the tables, on the beds and even under them. Indeed, every night we would remove the books to make our beds and every morning we would put them back there!

Having always been with books, reading stories and images came most naturally to me. And then, there was the dinner table at 2 Pushpa Colony, my home in Mumbai, which was the camp address for not only my cousins and unrelated uncles from Patna and Malda (the two places my parents came from) who were making a career in films, but also that for writers from Bengal and Bihar: Nirendranath Chakraborty, Santosh Ghosh, Samaresh Bose, Phaniswar Nath Renu, Debabrata Mukherjee…

The result? I grew up listening to discussions on literature and cinema – every aspect of it, from cinematography and editing to music and dance. Through them all, I came to appreciate not only the aesthetic aspects of these art forms but also their technical, economic and other social aspects. Through it all, unknown to me, I had become a film and art critic.

Your father moved from Bengal to Patna at the start of his life. Why? Did it impact his choice of career?

My grandfather Nabadwip Chandra Ghosh, a well-known Kirtan singer, was a much-respected advocate who moved from Dhaka to Patna, then a part of the Bengal Presidency, in 1920. Nabendu was then all of four. But every Durga Puja would find them back in Kalatiya village where he started by playing ‘sakhi’ (a woman’s role) and experiencing the rasa of devotion. In his school days itself Nabendu took to writing and soon was part of the editorial team bringing out a handwritten magazine which was popular in the Bengali society of Patna. From his early years he used to save from his tiffin money to watch movies. He was keen about dance and drama and in his college days he regularly performed – even in towns and cities outside Patna. All in all, he was trained in the Arts from his childhood.

And by 1942 he was already a published author. But what determined his ‘career’ as a writer was the Quit India call given by Gandhiji. It led to an incident that changed his life. A large crowd to assemble at the Government offices including that of the IG Police where Nabendu was then a junior. After witnessing the bloodshed unleashed by the British Police, he started writing a novel that labeled him into being identified as a ‘subversive’ writer. Realising that he would not get a respectable job under the imperialist government, he resigned from that job and again, from Military Accounts – and took to writing as a full time occupation and moved to Calcutta.

Why did Nabendu go to Bombay when he was such a successful and loved writer in Bengal?

We are all social creatures, and we do not realise how much our lives are tossed and turned by political events. Take the Partition of India: It bifurcated the state of Bengal, dividing the reader of books and the viewership of films. By 1947, Bengal was the most established film producing centre in India, and as a young, popular and respected writer endowed with a cinematic vision, Nabendu Ghosh was already writing screenplays for a Hollywood-returned director, among others. But both, the publishing sector and Bengali film industry suffered a humongous setback after Partition – especially as the newly formed Pakistan government decided to enforce Urdu as its lingua franca.

So, when faced with tremendous financial hardship, many successful directors moved to Bombay. Legendary director Bimal Roy too was invited by actor Ashok Kumar to make a film for Bombay Talkies, and he invited Nabendu to join the team as a screenwriter. The rest is a historic change of geography: the Bengali writer moved to the shores of the Arabian Sea but did not cease to serve the ‘Bay of Bengal’, as Sunil Gangopadhyay said in reviewing Eka Naukar Jatri ( Journey of a Lonesome Boat, Nabendu’s autobiography).

Here, allow me to quote what poet Nirendranath Chakraborty said at the launch of the autobiography: “It was not with any joy that Nabendu Da left for Bombay at the close of 1940s. The times were such that it was difficult for most of us to eke a decent living. He had a family to look after, the family was growing, opportunities were not. If anything, they were getting curbed. Nabendu Da fulfilled all his responsibilities, including to his family, his friends, and to his first love – literature.”

Recently his telling of Gauhar Jaan has been published in Mistress of Melodies, with some of his translated stories. But Gauhar Jaan was written by him in English — and very well written I must say. Why did he write it in English?

Nabendu was always a keen writer, and politically aware. He wanted to major in History but was advised to take up English. So, he did his MA in English – under British teachers. Naturally he had a firm grounding in the language.

In Bombay of 1950s, directors, actors, producers from different corners had converged. And so, although the discussions in Bimal Roy Productions were held in Bengali and Hindi, he wrote the scripts in English and the basic dialogue, though in Hindi, too was penned in Roman alphabet. So English was always his second language.

Besides, Nabendu had written Swar ki Rani or ‘Mistress of Melodies’ as the first draft for a fuller screenplay that he always planned to write – in all probability, for my brother Subhankar Ghosh who is a graduate from the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), directed the successful serial Yugantar (Over the ages) for Doordarshan and Woh Chhokri (That Girl) that won several National Awards.

Why did he not make a film out of Gauhar Jaan? It is an excellent story. Any plans to film it now?

Life is a hard task master. Subhankar too has had to go through several twists and turns. He was in Fiji for some years to teach filmmaking at the Fiji National University. That did not give him the scope to direct the film when Baba penned the first draft. If any opportunity comes along, I am sure that ‘Mistress of Melodies’ will be seen on the silver screen – or streamed on an OTT platform.

Nabendu was into script writing in a big way, especially for Bimal Roy. Can you tell us how they started working together?

After Nabendu moved base to Kolkata, Jahar Roy – the celebrated comedian of the Bengali screen who was like a younger brother to Nabendu since their Patna days – introduced him to Bimal Roy who had shot into national limelight with his very first film, Udayer Pathey (In the Path of Sunrise, 1943). The director, an avid reader, had read most of Nabendu’s writings and had observed that his writing had the “visual quality of a screenplay.” In particular he was highly impressed with the allegorical novel Ajab Nagarer Kahini (Tales of a Curious Land). But at that point B N Sircar of New Theatres was travelling abroad, so the project did not take off.

Meanwhile Mrinal Sen, then only a young associate of my father from Indian People’s Theatre Association, was eager to film it. He came up with a producer who unfortunately ran out of money within a few months and abandoned the project. Nabendu went back to Bimal Roy but he had firmed up his plans to shift to Bombay. All of a sudden, over a cup of tea, he asked Nabendu to join his creative team – and the writer was only too happy to get a new opening in the dismal post-Partition world.

Trishagni was an award-winning film by your father. Tell us how it came about and what made him pick the story?

In 1966 after Bimal Roy passed away, my father had started teaching the Direction students at Film and Television Institute of India as a regular Guest Lecturer. Soon the Film Finance Corporation (FFC) was reborn as National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) – and he became one of the revered members of its Script Committee. To create a bank of screenplays NFDC held a script competition and Nabendu won an award. It was not a cash award: NFDC supported the making of the film by way of equipment, editing, lab cost etc. That script became the award-winning Trishagni, based on a story by Saradindu Bandopadhyay, the Bengali litterateur best known as the creator of Byomkesh Bakshi.

Why this particular story? Being a writer himself, Nabendu would always go to literature for the subject of a film. He maintained that a writer puts in a lot of thought in rooting the character, into creating drama, in layering it with social concern. This gives a sturdiness to the visuals and adds to the fabric of the film which, in tinsel town, otherwise tend to become wishy-washy, and short-lived in their stimulation value. So even for Bimal Roy films he would suggest stories by writers like Subodh Ghosh, Narendranath Mitra, Samaresh Bose. These writers he not only read and respected, he would regularly meet them and often discuss the characters while scripting their stories.

Besides, being from Patna, he was fascinated by Gautama the Buddha whose statues in the museums generated “an inner feeling of content and peace”, he once told me. A prince who renounced every comfort, every pleasure in life in search of a truth, a ‘Bodh’ that would help mankind attain peace in his lifetime: this unique vision drew him to the teachings of Buddha. Then, in Maru O Sangha (The Desert and the Convent) he came across the Agni Upadesh, the sermon that outlined that the world is burning with desire, and our mission in life should be to free ourselves from desires that consume life. Only then we can attain a life of tranquility, endless bliss.

His reverence had inspired Baba to write a novel, Bichitra Ek Prem Gatha (A Wondrous Love, 2007) to mark Buddha’s 2550th year. It derived from the Buddhist text ‘Theri Gatha’ to juxtapose the worldly desires and longings with the exemplary discipline and distilled love of Pippali and Kapilani, two newly-weds who were drawn towards the Sakya Muni and took refuge in him. Eventually Pippali turned into Mahakashyap, a ‘lieutenant’ of the Buddha, and Kapilani headed the ranks of nuns – probably the first convent in the world! This turned out to be Baba’s last published novel (while he lived).

While on his Buddha Trail, let me add that Nabendu had earlier been part of Gotama the Buddha (1956), the Bimal Roy Productions documentary that had won director Rajbans Khanna an Honorable Mention at Cannes.

What was the last film he made? And what was the last book he wrote?

The last film he was to make – on NFDC funding – was Motilal Padre, based on a novel by Kamal Kumar Majumdar. Unfortunately, this remained an unfulfilled dream. So, effectively, he directed three films: Trishagni (1989), Netraheen Sakshi (Blind Witness, 1992) for the Children’s Film Society of India, about a visually challenged boy who could identify a killer by his voice, and Ladkiyaan (Daughters, 1997) for the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

This again was part of a scheme that saw the Ministry finance films pertaining to a Girl Child’s education (Kairee by Amol Palekar), childbearing and women’s health in a Muslim family (Hari Bhari by Shyam Benegal), and so on. Ladkiyaan was based on a real-life incident that saw three sisters in Kanpur jointly commit suicide when one night, they heard the father threatening their mother, who had conceived again: “No more girls! I want only a boy.”

His last completed novel is Kadam Kadam (The Long March), which chronicles the story of a young Indian who joins the British Army, is sent to Singapore, taken POW by the Japanese, joins INA and is transformed. He had just completed it when he had to be hospitalized. I published it at the onset of his birth centenary.

He wrote a book for his grandchildren too. Would you like to tell us about it?

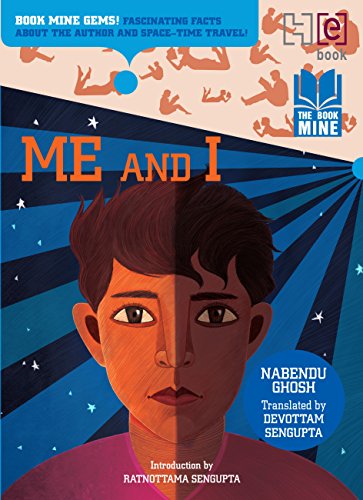

Yes, he wrote Aami ar Aami, translated to Me and I, for his two grandsons, Devottam Sengupta and Devraj Nicholas Ghosh. The racy story about a parallel universe fuses human curiosity about outer space, the stars and galaxies, with a futuristic vision emanating from his faith in humans and a ‘Hindu’ vision of the cosmos…

The germ of the story came from Sudheesh Ghatak, the second brother of celebrated director Ritwik Ghatak, whom I remember from my childhood as a fascinating storyteller and a storehouse of knowledge on the developments in science as well as on the ‘Unbelievable’. One day he had talked about the hypothesis of a group of scientists about twin planets in the cosmos. A few weeks later Nabendu, on a visit to Kolkata, was leafing through old books sold on the pavements of College Street, and came across one that referred to twin planets. That spurred his curiosity, and imagination…

My son, Devottam, started translating the book as part of my effort to improve his Bengali. He believes that somewhere the idea grew in my father from watching his two grandsons. When they were kids Dev and Nick — who now lives in UK — were mistaken for twins. At one time my brother was posted in Germany, and his friends would remark how the cousins resembled each other yet were “somewhat different”. This could have fanned his thoughts about the protagonist and his interstellar twin who were ‘identical yet opposite’. In Me and I, Mukul (which, incidentally, was my father’s pet name) and Lukum “mirror, in a modified way, our experiences of growing up as two brothers separated by what in 1980s was several thousand miles of culture – experiences, of what we were exposed to and how we were brought up in our thinking,” Devottam wrote in his translator’s note.

What do you feel when you translate Nabendu’s work?

You have taken the words out of my mouth. Actually, translating Nabendu Ghosh has been a BIG lesson in creative writing. His stories are rooted in the soil, yet not homilies on traditional lives. They are about the lives impacted by social and political twists that tossed people not only across the Radcliffe Line but from Bengal to Bombay, Madras (now Chennai) to the Himalayas, from villages to the industrialising cities, the lost world of Lucknow’s nawabs to the Bengal heightened by World War II, to the dreamland of Bollywood and the upper crust families homed in Park Street.

Layering a character with socio-political reality makes them both universal and timeless, I learnt as I tried to translate these stories. There’s always a tomorrow to live for, I learnt from them. The more direct your sentence is, the more crisply is the emotion conveyed, I learnt from his sentences. The shorter the sentence is, the more it compels you to walk ahead with the characters into their lives. And, of course, from his use of language I learnt that every word we utter is a reflection of my time, my mood, my upbringing. As Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay said, Nabendu Ghosh is a writer who should be read by every aspiring writer for his grasp over the art of storytelling.

Tell us what was the perception about his writing and its impact on his peers and writers who came after him?

When Nabendu entered the frame, the towering personality of Rabindranath Tagore was no longer on the scene. There were the three Bandopadhyays – Tarashankar, Manik and Bibhuti Bhushan. The three ‘N’s – Narayan Gangopadhyay, Narendranath Mitra and Nabendu Ghosh joined them at this juncture, each with a definite voice and constituency.

On his 90th birthday, litterateur-journalist Dibyendu Palit wrote: “Nabendu Ghosh is among those frontrunners of the post-Kallol era Bengali literature who amazed with the power of their pen. His subjects were rooted in realism, his language was seeking new expressions in aesthetics. His Ajab Nagarer Kahini, Phears Lane, Daak Diye Jaai are memorable creations in the language…”

Sunil Gangopadhyay summed for the Indian PEN Society, what he wrote in reviewing Eka Naukar Jatri: “Your devotion to Bengali literature and your creativity in the language is a matter of great joy for us.”

Last year Shirshendu Mukherjee, speaking at a celebration of Nabendu’s birth anniversary at Starmark said, “Nabendu Ghosh was a ‘star’ among those writing in1940-1950s. He lived a long life — he passed away when he was nearing 91 — and almost until he went away, he was writing. My attraction for his work was formed when I was a teenager reading world literature. There were two names I admired very much Norwegian Nobel laureate Knut Hamsun (1859-1952); and Austrian Stefen Zweig (1881-1942), the most popular novelist of his time. Anyone who read him can’t forget his style of writing. In my view, Nabendu Ghosh shared his trait of riveting storytelling with Zweig. The same focused development of a plot shorn of every trivial and expendable branch, razor sharp emotions, whirlwind passion — I feel writing itself was a passion for him. He did not write with his head alone, his heart bled for the human condition. This I can say without exhausting the considerable list of his writings — 28 novels, 18 anthologies of short stories.”

Shirshendu also talked about Nabendu’s remarkable use of language. “One of his stories starts with a word, “Bhabchhi — (I’m) Thinking.” It is a single word that is also a complete sentence, and it has been used as a paragraph in itself. Not many writers of his time were into such experiments. Even some doyens of Bengali literature did not accept to set out on this adventure. Nabendu Ghosh did. He stood apart from his contemporaries in this respect. A part of his mind always ticked away, thinking of how his characters would speak. This has to be done – this tinkering with structure, altering of syntax, or adding to the vocabulary. Words from so many languages — Arabic and Persian and English – have filtered in and become a part of the Mother Language as we speak it today.

“Nabendu was always pushing the boundaries of the language – but he had an amazing sense of the optimum in this matter: he never overdid it. One of his stories, Khumuchis, explores the secret language used by pickpockets. Bichitra Ek Prem Gatha (A Wondrous Love) – published to mark 2550th year of Buddha — uses language that is closer to Prakrit, in that it is devoid of any word that would not have existed before the advent of Islam. He always put a lot of thought into how the characters would speak. This added to the readability of his stories and quickened the pace of the narrative. They were all so racy!

“And this is why he never dated. His writing is the stuff that makes a story universal, eternal. For today’s readers he is a lesson in how to write — they can master how to write a narrative that flows like a boat down a rapid stream. In terms of language, structure, characters and situation, he is a writer who would be relevant to the young readers of not only Bengali but worldwide.”

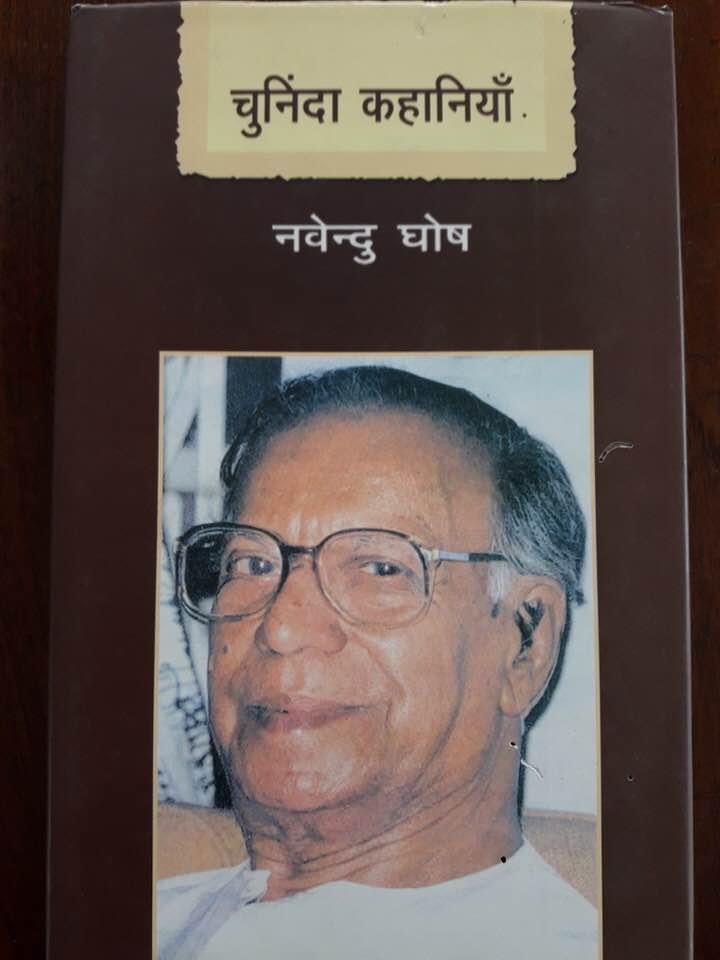

Speaking at the launch of Chuninda Kahaniyaan: Nabendu Ghosh (Chosen Stories of Nabendu Ghosh, stories translated to Hindi) the recently demised thespian Soumitra Chatterjee, a Master in Bengali Literature, had said: “Even before I took to studying Bengali literature, even when I was in school, Daak Diye Jai (The Call) was a sensation. His writing was not confined to urban settings and city life, he wrote of the man of the soil too. His characters were always flesh and blood humans too.”

And when his last birthday was being publicly celebrated at the Palladian Lounge in Kolkata, an MA student of Rabindra Bharati University, Saswati Saha had said, “This bright star of contemporary Bengali literature has riveted me with the quiet aesthetics and deep realizations that are germane to his novels. I am a young reader of his art but both Bichitra Ek Prem Gatha and Jibaner Swad (The Taste of Life), both published in 2007, have increased my appetite for his writings. With the alluring simplicity of his language and unhurried descriptions he unfolds harsh realities. Had I not read Nabendu Ghosh, I would have remained ignorant of a large tract of life experience.”

You yourself have made a directorial debut on the life and works of your father. Did that help you understand him better? How did the film do?

And They Made Classics… was made to celebrate his Birth Centenary in 2007 but the interview it came out of was recorded by Joy Bimal Roy and Aparajita Sinha – son and daughter of Bimal Roy when they set out to make Remembering Bimal Roy in his 100th year. ATMC… spoke primarily about the classics of Nabendu scripted for the legendary director. It is a lesson in film appreciation and also in a certain way, about the art of making films in a given social circumstance – in the face of all odds. It seasoned me as a film analyst, really.

Of course, what has given me a greater insight into his life and times is Eka Naukar Jatri, the autobiography that was first serialized by Dibyendu Palit as the editor of Sangbad Pratidin (News Everyday) then fleshed out by the writer for Dey’s Publication. Now, while translating it for Speaking Tiger, it lifts the curtain on how he became a litterateur, virtually chronicling 1940s, the founding decade of our nation. This was a decade that was ushering the future in tumultuous colours and fiery alphabets. Just think of the march of the dead this decade saw: people dying on the streets of Calcutta while the British government was sending away rice to the theatre of war in the North East; people dying in poisonous chemical vapour unleashed through Europe; lives lost in Japan when a new atomic toy was dropped from the air – and later, repeatedly in the Pacific Islands, when millions suddenly were tossed into an identity crisis and an ensuing bloodbath by the Radcliffe Line…

I now understand that he was constantly bothered by questions such as “Is this the new era, the age of Deliverance to be ushered by the mythical avatar, Kalki? Or will this flow of blood and the wails of mothers be lost in the dust? Will the world be green again?” I now understand why the Lifetime Achievement Award citation of Bengal’s literary council, Bangiya Sahitya Parishad reads: “Time and again the strange ironies and mysteries of history have lit up your questioning mind. At the centre of history is Man. History is the conveyor belt that leads Man from past to present, sometimes with affection, mostly through rough and tumble. History never stands still through conflicting turns of events it makes way ahead. You made history stand still in your pages…”

You have written a number of books and translated extensively. What is the difference between your father’s writing and yours? Of course, you are an eminent journalist, and he was a creative writer. He wrote in Bengali and Hindi mainly. And you write in English. But, other than that do you find any similarity in the way you tell a story? Has he impacted your style?

Now you must bear with me as I talk about myself!

I am what I am as a writer because I was born in the household of Nabendu Ghosh – and here I am not talking of DNA or of dynastic inheritance. As I have said before, our house was full of books and I grew up leafing through them even when I didn’t know whether they were in English, Bengali or Hindi. I had a lovely childhood reading Bengali ‘kishore sahitya’ – literature for young readers – as much as Enid Blyton, Mark Twain, Phantom and Amar Chitra Katha comics. At BES School in Dadar, we annually celebrated Saraswati Puja by ‘publishing’ a handwritten magazine of stories and essays by the students – and that was my haatey khari — initiation as a writer. Here too, I would discuss a story idea and my father would tell me how the characters would think or act, never how to write, what language to use or how to structure the story.

Perhaps that is why, although I scored the highest in our school when I matriculated in 1971, securing in 96 and 97 in Science and Math, I joined Elphinstone College, then celebrated for its Arts stream and Mastered in English and American literature, with the added advantage of fluidly moving from English to Bengali and Hindi, Marathi and Gujarati. In other words, through Indian literary traditions as much as the wealth of world literature. That helped me to decide that I will make life either as a journalist or in academics, careers that would see me read and write every day.

It so happened that in 1978, when I returned from England after eight long months of holiday with my brother Dipankar, I applied for two jobs: a trainee sub-editor at Indian Express, and lecturer at the National College in Bandra – both at the instance of my friend Imran Merchant, erstwhile Editor of TV World. As life would have it, I got appointment letters from both, first from the daily, and a month later, from the college. I didn’t know which way to go, so I went to Ms Homai Shroff, then the head of the department for English in Elphinstone. When I told her my dilemma, she retorted: “What! You are already in journalism, and you want to move to academics? Don’t be stupid!” That decided it…

But let me add that eventually I did get to teach as well. Although for a short term, I was guest lecturer at Delhi University’s Kalindi College; I taught young entrants at the Times School of Journalism; I have been Mentor to Mass Com students at Lady Shriram College…

Journalism carried my name to virtually every corner of India. It gave me an opportunity to travel across the globe. It brought me into contact with the biggest names in the world of Arts – painting, music, dance, theatre, literature and of course cinema. All this made Baba happy and quietly proud. But he nursed one objection: “Journalism is short lived and mostly goes into highlighting other people’s achievement. In doing all this, you are expending your time and literary energy. Turn your attention to your own creative writing,” he would urge.

Similarity of style? I don’t think so since we were doing very different kind of writing. But impact, yes, and I have already said how.

What are your future plans? With translations? Films? Your own writing?

All of them. I plan to keep translating, and not just my father’s work. God willing, I will certainly make a few more films. I am halfway through Menaka to Mallika, a documentary study of dance in Hindi films. I hope to make a short feature on trafficking and a full length one on a father-daughter story. As for my own writing, there are talks of publishing them. Ambitious? Perhaps. But like my father I would like to read and write till the last day life grants me.

This interview was conducted online by Mitali Chakravarty.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.