By Ratnottama Sengupta

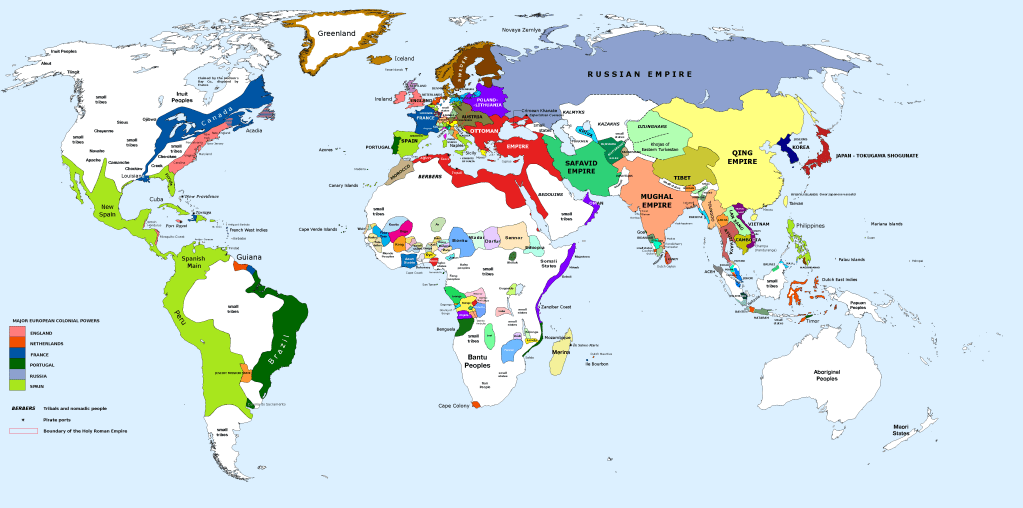

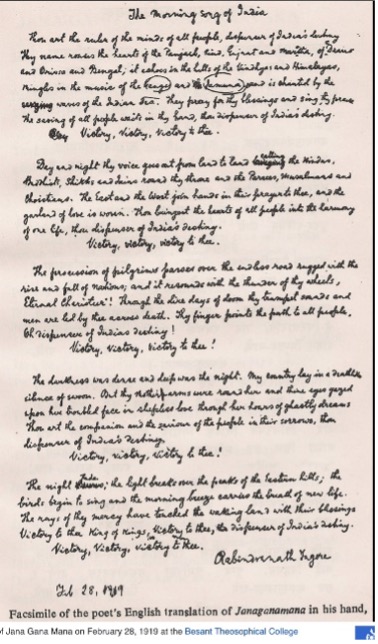

Rabindranath Tagore spells different things to different people: National Anthems; the Nobel, Rabindra Sangeet, a veiled woman, Sriniketan or Santiniketan. A cineaste might think of Charulata or Kabuliwala, Chokher Bali (Best Friend) or Kadambari. But the subject ‘Tagore and Cinema’ would mean talking of Tagore’s exposure to cinema, his interest in the medium, the fate of his involvement with celluloid, the films based on stories penned by him, their interpretation in a world that is so far removed from his, in historical, economical, and cultural terms… In other words, it would mean talking of what about Tagore endures — and why it reaches out to the wide world of humanity.

To me, it is Tagore’s awesome, inspiring humanism that offers us immense scope to transcreate, reinterpret, relocate the socially relevant developments and rooted characters again and again onscreen. Like Shakespeare, his works are universal in terms of age, geophysical location, terrain of the mind and tugs of emotions…

Rabindranath was almost seventy when he exhibited his paintings that were so radically different from the style associated with the Tagore family artists, Abanindranath, Gaganendranath, Sunayani Devi, or Nandalal Bose. For, if the Bengal School looked East and sought inspiration in delicate miniatures, Chinese watercolours or the sparseness of Japanese zen, Tagore absorbed the boldness of German expressionism and created a unique style. It’s impossible for someone so open to avant garde trends to take no interest in cinema, the 20th century art form that was silently taking its juvenile steps in India when Tagore won the Nobel.

When he visited Russia, he watched Battleship Potemkin, the classic ‘handbook for editors’ (to quote Phalke winner Hrishikesh Mukherjee) that influenced a long line of filmmakers in India too. By 1931, the year when Alam Ara (Hindi) and Jamai Shasti’(Bengali) turned ‘movie’ into ‘talkie’, Tagore was in the last decade of his life. So, when he directed Natir Puja (The Dancing Girl’s Worship) at New Theatres, he was substantially assisted by Premankur Atorthi, who was the first to direct a film based on a Tagore composition. This was the only time when the Renaissance personality directly interacted with the celluloid medium. His nephew Dinendra wrote the screenplay, albeit under Tagore’s guidance, and students of Santiniketan acted in it. More importantly, Tagore himself essayed an important role in the dance-drama which was shot with a static camera over four days. However, the result was more a staged play than cinema. A greater tragedy is that the reels perished within 10 years, when a fire ravished the New Theatres Studio in 1941.

Atarthi’s own direction of Chirakumar Sabha (1932) set off a tradition that received a robust boost, first in the 100th year of the poet’s birth, and again in 2011, when he turned 150 and further. If literary treasures like Gora (1938) and Chokher Bali (1938) were adapted onscreen by Naresh Mitra and Satu Sen, they were remade and reinterpreted by Rituparno Ghosh who veered towards Tagore rather than Saratchandra, the more popular litterateur of Bengal who was a staple of Tollygunge for years. In fact all major names of Tollygunge, from Nitin Bose, Agradoot, Tapan Sinha, to Purnendu Pattrea, Partha Pratim Chowdhury and Rituparno Ghosh have announced their coming of age in cinema with a film based on a Tagore composition.

It is interesting to note that when Tagore visited Russia in September of 1930 members of the Cinema Board who had a conversation with him regarding his “new film stories” were deeply impressed by the short versions of the stories (as narrated) by the Poet, and they met him at his hotel to discuss in detail the possibilities of filming them. Tagore himself had enough interest in cinema to visit the Amalgamated Cinema Union, where he was received by its president M Rutin and was shown Eisentein’s Battleship Potemkin and portions of Old and New, we learn from his Letters from Russia.

Although evoking the Bengal of his time in divergent hues, Tagore’s stories continue to inspire man to go beyond divisions of nation, religion, caste or gender, perhaps because they explore how society shapes our love and relationships. This essay dwells on films that highlight the pervading themes of feminism, humanism and universalism in Tagore’s literary works.

Not Slave, Nor Goddess

The champion of women tells us to enunciate aami nari, I am a woman … with pride, because a woman is not a slave nor needs to be the other extreme, a goddess. That it is right for a woman, whether young, maiden, or widowed, to be a person of flesh and blood. That Tagore empathised so deeply with his women characters that today’s social historians are talking of an androgynous strain in the humanist.

* When Satyajit Ray filmed Ghare Bairey (The Home and the World), we got a glimpse of the regressive practices that ailed even the wealthy and educated households. However the most symbolic scene was the one where Bimala is inspired by Nikhilesh to step out of the inner quarters of the zamindar’s household. Even Sandip, the false god, hails it as a ‘social revolution’. Tagore the author goes on to criticise the pseudo rebel but at no point does he criticise Bimala — not even when her sister-in-law cautions Nikhilesh about the freedom his wife is abusing. We find a repeat of this theme in Char Adhyay (Four Chapters) – but we’ll come to that later.

* Chokher Bali, first filmed in 1938, turned the spotlight on the deprivations young widows were subjected to even after the reformist crusades of Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar. Very sympathetically, and most aesthetically, it held a brief for their sensuality — even sexual needs, especially when Rituparno Ghosh filmed it in 2003. But even here, before Mahendra’s mother dies, she urges that in her memory he should host a feast for widows — “people feed Brahmins, beggars, even animals, but never for the unfortunate widows,” he underscores.

* Nitin Bose’s bilingual Noukadubi was probably the first to take Tagore to Hindi cine-goers. Incidentally Rituparno and Subhash Ghai’s Noukadubi were also bilingual. In 1944, Milan afforded Dilip Kumar opportunity to mature as an actor, for here Ramesh upholds the flag of humanism. After being boat wrecked he comes home with Kamala, the ‘bride’ he has not deigned to look at, and realises that she is in fact someone else’s wife. The gentleman in him decides to take her to a convent and give her not just protection (from a par purush, stranger) but also proper education — even at the cost of his own spotless reputation and his chances of finding happiness with his beloved, Hem Nalini.

* In Charulata (1964), although Satyajit Ray continues to unfold her story from Amal’s point of view, his sympathy without reservation lies with the lonely wife. For half a century and more viewers have no doubt that Charu was an alter ego for Tagore’s Natun Bouthan – his sister-in-law Kadambari Devi, who took her own life. This story has inspired Bandana Mukherjee’s Srimati Hey and Suman Ghosh’s Kadambari (2015). Ray underscores this aspiration aspect in the film when Charu writes, gleaning from her experiences, and her writings are published in a magazine. This was unthinkable in the 19th century — and only a deeply humane soul could understand that a woman too needed to express her intellectual and creative self. (This aspect is completely missing in Charulata of 2011, directed by Agnideb Chatterjee, although it unfolds from the woman’s perspective and unabashedly speaks of her physical intimacy with Amal.)

* For Tagore, perhaps the stifling of this intellectual self was as great a tragedy as the ‘burying’ of her potentials within the walls of domesticity. In the poem ‘Sadharan Meye’ (Ordinary Girl), he urges his contemporary Sarat Babu to write a novel where the protagonist — a scorned woman — goes on to study, travel abroad, re-valued by several admirers, including the man who ditched her for being an ‘ordinary’ woman. The core thought of this poem had inspired a script by Nabendu Ghosh, an altered (and unacknowledged) version of which was made by Hrishikesh Mukherjee as ‘Pyar Ka Sapna’ (Dream of Love, 1969). In recent times the theme has been most successfully revisited in Vikas Bahl’s Queen (2014).

* In Megh O Roudro (Clouds and Sunshine), Rabindranath’s short story creates a protagonist whose struggle to affirm her dignity in the British ruled 19th century prompts her to read and write under the tutorship of a stubborn law student who is jailed for constantly challenging the discriminatory ways of the imperialists. By the time he is released, she is a prosperous widow who courteously acknowledges his role in her achieving self-confidence. In 1969, Arundhuti Debi, herself raised in Tagore’s ethos at Santiniketan, chose this for her second outing after Chhuti (Holiday) and her lyrical treatment brought her recognition as a director of substance.

* But what happens when a woman cannot fulfill her destiny, as in Streer Patra (A wife’s Letter, 1972)? How did Rabi Babu want his Mejo Bou — haus frau — to behave when the acutely male dominated household turns a blind eye to the injustice of marrying off the hapless orphan Bindu to a lunatic? Not drown her woes in the vast ocean at Puri but to slough off, in a moment of illumination, the shell of ‘Mejo Bou’ and become Mrinal, a woman with .her own soul and individual identity Why must she end her life like his Natun Bouthan — “Meera Bai didn’t,” he points out. And to us, even by today’s standards, it is the ultimate expression of feminism.

* Perhaps because of the class she belonged to, and with the support of a rebellious brother, Mrinal could do what Chandara couldn’t in Shasti (Punishment, 1970). Tagore knew that neither his ‘Notun Bouthan’ nor his own wife Mrinalini got the opportunities enjoyed by his ICS brother’s wife. Far from it: Chandara’s husband Chhidam places the burden of his Boudi’s death at the hands of his elder brother on his wife. In the prevailing patriarchal society it wasn’t unthinkable: a wife was expendable because you could get another, but not a brother. But the unlettered Chandara has her own estimation of the sanctity that is the conjugal bond. When her husband comes to meet the wife condemned to hang, she denies him the right of visitation by disdainfully uttering a single word: “Maran!” How should we read it today? Go, drop dead or go hang yourself!

* Jogajog (Connection) was written in 1929 in a society where there were caste/ class distinctions even amongst zamindars. Tagore had first-hand experience of this within his family. His crude protagonist is a johnny-come-lately who seeks revenge by marrying the educated and cultured Kumudini. He cannot stand any expression of respect for her brother and feels belittled at the slightest hint of will in his wife. Matters go so far that in the 2015 film, director Sekhar Das can effortlessly trace moments of marital rape in their conjugal discord.

* Chitrangada had poised the question: where lies a woman’s true beauty – in her outward appearance or her inner worth? Should the princess, raised to be as good as a prince, deny her essential self to please a man? Or is she wrong to sacrifice her being for one she loves? In 2008, Rituparno Ghosh gave a whole new androgynous reading of the dance drama, with Madan/ Cupid becoming a psychoanalyst.

Child — The Father and Mother of Man

Robi, who immortalised his childhood in Chhelebela (Boyhood), could never forget the restrictions imposed by adults and the suffocating effect it had on an imaginative soul. Therefore in Ichhapuran (Wish Fulfillment,1970), directed by Mrinal Sen for the Children’s Film Society of India, he effected a role reversal whereby their bodies get swapped. The naughty child Sushil becomes the father and the senior who covets the youthfulness becomes the free spirited son.

The comical confusion this ensues in the village leads both to realise the importance of their individual positions in life. They get back to their original self with the profound lesson for humanity – that each one of us has a place in the world no one else can ever fulfill.

* Of course the best known child in Rabindra Rachanabali (Creations of Tagore) is Amal. Essentially Dakghar (Post Office) was a testimonial against the crushing of childhood Tagore suffered. In the recent past actors Chaiti Ghoshal and Kaushik Sen have proved the enduring appeal of Dakghar — she in the form of a recorded audio play (CD); he on stage. Chaiti Ghoshal interprets the protagonist she had played with Shambhu and Tripti Mitra not as a Rabindrik character but as any child today, familiar with cricket and computer. Manipur’s Kanhailal has used elements of dance and drama to reinforce this message of freedom beyond frontiers. And, following the 2007 police firing in Nandigram (that killed 14 persons who were opposing state officials on land acquisition drive), Kaushik Sen had interpreted Amal’s desire to send a letter as a message to every household to raise awareness.

Sen’s Dakghar, then, was not about death but about liberation from life in bondage. “Perhaps that’s why, a day before Paris was stormed during WWII, Radio France had broadcast Andre Gide’s French translation of the play,” Kaushik had said while staging the play. “Around the same time, in a Polish ghetto, Janus Kocak had enacted the play with Jewish kids who were gassed to death soon after.” After such multi-layered readings of the text, Dakghar as filmed by Anmol Vellani in 1961 remains a simplistic viewing — perhaps because it was made for the Children’s Film Society.

* In The Postmaster the child – an illiterate village girl in this instance – metaphorically becomes a mother and a priya , or beloved, of the pedantic city boy who is stirred by beauty of the moon but can’t wait to go back. When he falls critically ill she dutifully serves him and cares for him like a wife. When he is set to depart by simply tipping her with silver coins, the child with a maturity beyond her years refuses to say goodbye. Rejection doesn’t need words: she can negate his very existence by her silence.

* Samapti (Finale) the concluding story of Teen Kanya (1965) remade by Sudhendu Roy as Upahaar ( The Gift, 1975), builds on the flowering of a woman in an unconventional girl child. Mrinmoyee is certainly not a Lakkhi Meye…a good girl , she’s a scandal in rural Bengal of 100 years ago. She escapes her wedding night by climbing down a tree, she spends the night on her favourite swing on the riverbank, she snatches marbles from her friend, a boy… When they try to tame her by locking her up in a room she throws things at Amulya. But when he returns to Calcutta and she’s sent back to her mother’s, she realises grown up love for the man she’s married to, and sneaks into his room by climbing the same tree!

* Buddhadev Dasgupta had woven Shey from Tagore’s late novel written for his granddaughter, and then scripted a feature based on 13 poems by the bard. When we read a poem, certain images arise before our mind’s eye. The director interprets Tagorean poetry through such images and experiences. “It is about how a poet responds to another poet,” he explains.

Of Zamindars and Servants

Robi, the ‘good for nothing’ youngest son of Debendranath, had to prove himself in his father’s eyes by successfully performing the job he was entrusted with – that of collecting taxes, ‘khajna’, from the ‘prajas’, subjects, no matter how impoverished they were. We all know that in doing the job he came across a vast cross section of people of the land whom he would not otherwise get to know so intimately. And while he could not be lenient as his father’s representative, he created caring characters like the zamindar in Atithi ( The Guest) who brings home a vagabond, gives him education, and even prepares to give his daughter in marriage to the free spirited boy whose restless soul drives him away…

* But having seen the reality of the lives of the subjects Rabindranath also created uncaring zamindars like the one in ‘Dui Bigha Jami’ (Two Bighas of Land) that had inspired the Bimal Roy classic Do Bigha Zamin (1953), set in a post-independence India that was rapidly industrialising. Debaki Bose attempted a more literal visualisation as part of Arghya, his Centenary Tribute to Tagore, along with his poem ‘Puratan Bhritya’, (Old Retainer).

* Robi, the motherless child who was raised in a large household in the rigid care of servants, said ‘Thank You’ to them through characters like Kesto, the old family retainer who refuses to leave even when he’s dubbed a thief or driven away. Instead, he saves his master from small pox at the cost of his own life. Tagore, in fact, goes a step further in his short story, ‘Khokababur Pratyabartan’. The trusted servant even raises his son to eventually give him up as the master’s child lost to a landslide in the river!

Oppression of Religion

Pujarini (Worshipper) was immortalised by Manjushri Chaki Sircar’s dance. Although set in the revivalist times of Ajatshatru who was set upon putting the clock back and wipe out the Buddhist tenor of his father Bimbisara, we can easily identify with Rabindranath’s condemnation of any excess – violence in particular – in the name of Religion. Visarjan (Immersion) too raises consciousness against violence in any form, against even animals, in the name of religion.

* Nor can we overlook instances where he raises his angst ridden voice against the inhuman treatment of humans on grounds of caste or creed. In Chandalika, the untouchable gets a new mantra to live by when the Buddhist monk Ananda says “Jei manab aami sei manab tumi kanya (You, lady, and I are part of the same humanity).” The act becomes a beacon for Sujata, the eponymous protagonist of Bimal Roy’s film, who is on the verge of ending her life (following casteist discrimination).

* Tagore’s poem called ‘Debatar Grash’ (God’s Greed), lashes out against the cruelty people can unleash through the heart rending plight of the mother whose child is snatched from her and thrown into the raging waters to appease the villagers superstitious belief in god’s wrath. Shubha O Debatar Grash (Shubha and God’s Greed, 1964) remains a signature film of Partha Pratim Chowdhury.

* Tagore questioned the very concept of belonging to ideological boxes. His time-transcending novel, Chaturanga (Four Quartet), points out that human experiments (like, say, Communism) have failed because they put ideology in watertight boxes that do not have any room for flexibility. This inspired Suman Mukhopadhyay to film it in 2008. Tagore, who himself created walls and broke them, questions this through Jyathamoshai, his uncle, and Sachish, who invite Muslim singers and feed them at shraddha or funeral as much as through Damini, whom Sachish wants to domesticate much against her wish. She even questions her husband’s authority to will her away along with his property, to his religious guru. Tagore uses the graphic imagery of a hawk and a mongoose that Damini has as her pet (it is well known that these animals cannot be domesticated).

Nationalism to Internationalism

‘Where the world has not been fragmented by narrow domestic walls, and the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habits: into that heaven of freedom’ Tagore, forever and always, wanted his compatriots to awake. That is why Nikhilesh, in Ghare Bairey, does not condone violence even in the name of nationalism. That is why he decries Sandip, who uses the passion of young freedom fighters and the wealth of the poor to fill his coffers.

Beware the false god: Tagore repeats the criticism in Char Adhyay. In 2012 Bappaditya Bandopadhyay revisits the novel filmed by Kumar Shahani in 1997, the golden jubilee of Independence. But Ela’s Char Adhyay review it for its politics, its backdrop of ultras and violence, for the debate that acquired a new validity in the world after 9/11. Tagore was much in favour of non-violence, so much so that he criticised the nationalist movement too when it turned violent. How much of a visionary he was to ask a full century ago: “What will be the state of the nation that is based on violence?”

Young filmmakers are amazed by Tagore’s vivid criticism of the deterioration of party structures although he himself never belonged to any party. Sarat Chandra’s Pather Dabi (Demands of the Path), written about eight years before Char Adhyay, had taken a populist stand while Tagore didn’t hesitate to say through the protagonist Atin, ‘I am not a patriot in the sense you use the term.”

* That Rabindranath was against any form of regimentation is well established. His play, Tasher Desh or the land of cards, perhaps, written to criticise the submission of the conscience in Hitler’s Germany, remains the ultimate critique of regimentation. Directed by Q in 2012, the text layers his criticism of contemporary society by “trippy” visuals. By Q’s own submission, it is a “quirky” retelling of the Tagorean allegory.

* Gora (directed by Naresh Mitra in 1938) goes further: He bows to his adopted mother, hails her as his Motherland and says, every child is equal for a mother, she does not differentiate on any ground. Tagore here gives us a blueprint for an ideal Republic where a hundred flowers can fill the air with a hundred different colours.

* Perhaps the ultimate example of Tagore’s humanism is Kabuliwala, directed in Bengali by Tapan Sinha in 1958 and in Hindi by Hemen Gupta in 1961. An Afghan selling his wares in a Calcutta 150 years ago and striking a friendship with a child who reminds him of his own daughter back home, is a story that will strike a chord in anybody, anywhere in the world, at any given point in time — even in a world swamped with internet, chat rooms, mobile phones and multimedia messaging.

All of this reiterates the ‘forever-ness’ of Tagore. It also redefines the need to interpret his farsightedness, his comprehensiveness, his universality for our own times, in our own terms. Tagore himself had observed in a letter: “Cinema will never be slave to literature – literature will be the lodestar for cinema.” So we may conclude that since Tagore was primarily delving into human emotions, into the psyche of men and women placed in demanding situations that forced them to measure up to social, political, cultural or gender-based challenges, films based on his stories not only continue to be made but find an ever-growing audience in the globalised world.

(Courtesy: Tagore and Russia: International Seminar of ICCR 2011 held in Moscow. Har Anand publications, 2016. Edited by Reba Som and Sergei Serebriany)

.

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and write books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International