G Venkatesh writes about a book from 1946. What is interesting is no women writers are featured in it despite their being a phrase which he quotes in his essay, ‘a stepdaughter of the Muses’…

There is this book published in 1946 in New York, that I picked up at a Red Cross charity shop in Karlstad (Sweden) of late. A compilation of micro-biographies (make that ‘nano’ if you will) of 20 novelists (fiction-writers in other words) from Italy, Spain, France, England, Scotland, the USA, Russia and Ireland, who graced the world of literature in flesh between the mid-14th and the mid-20th centuries, and will continue to do so, in spirit, forever.

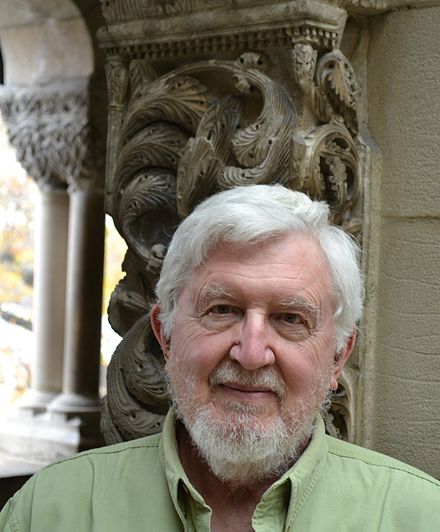

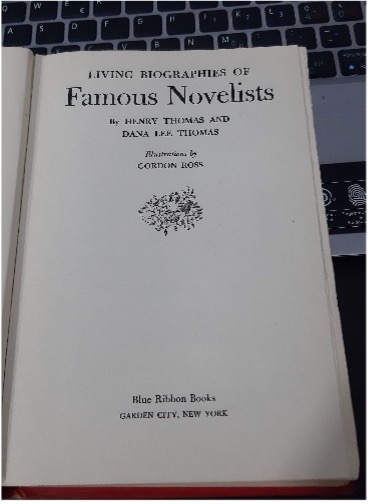

Visual by G Venkatesh

I venture in this article to present some gleanings from this little gem of a book, to enlighten, motivate, inspire, educate and rekindle interest in the classics of yore. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that all writing happens by the grace of God. We witness that in the lives of the twenty writers profiled in the book. Some had an inborn urge to write, some developed the penchant to do so as if the idea floated in from the idea-realm beyond the astral, and some others were blessed by the Divine to transmute their pain and suffering to the written word that has stood the test of time, and will continue to do so, into the distant future. Condemnation paved the way to commendation for some, while rejections emboldened others to transcend the limits of human judgement and rejoice in the sunshine of hard-earned glory.

At its perigee, the ‘novel’, as observed by Henry and Dana Lee Thomas, is an epitome of philosophy as applied to life. The Thomases ask readers to consider the life of every novelist profiled to be a magnum opus in itself – each adorned with facts stranger than fiction.

Boccaccio, Rabelais, Cervantes

This is an Italian-French-Spanish trio (encompassing the 14th to the early 17th century), and perhaps most of the readers may be familiar only with the third-named. Giovanni Boccaccio was a contemporary of Alighieri Dante (whose biography he wrote). A ‘friendly sinner’, he was a devotee of the here and now, while also being profoundly interested in the hereafter.’ Novelists, well and truly, leave behind accounts of their times, couched in fiction (and that, read alongwith factual history, helps us readers to visualise and understand better how things were in the past). The ‘poets’ in them, simultaneously dwell on and dream about how things can, must and will be in the future. Many of them refrain from including a semi-autobiographical element to their novels, and the Thomases have identified Francois Rabelais as being one such. To the Frenchman, all life was an anecdote with a bitter ending, a truth he based his limited fictional creations on.

Miguel de Cervantes, the Spaniard, is presented as a disappointed, shattered and disgusted man, who was chiefly motivated by his own trials, travails and tribulations to pen the famous Don Quixote. This knight who fought windmills, was perhaps what Cervantes thought himself to be – blessed with the good fortune to live in folly and die in wisdom.

Defoe, Swift, Sterne

From the simple Quixote and the clumsy Sancho Panza to the resourceful Robinson Crusoe and his helpful Man Friday, characters created by Daniel Defoe in a novel eponymous with the protagonist. Defoe was a paradox of moral integrity and material ambition (if you can visualise one such blend), who by virtue of the fact that he donned the mantles of businessman, pedlar, politician, pamphleteer and spy (not necessarily in that order) in his life, could interpret mankind expertly in his fiction. A kind of ‘been-there, seen-that, done-that, can-write-about-all-with-authority’. Jonathan Swift, of Gulliver’s Travels fame, was gifted with a supreme intellect and a spiritual-religious leaning, but encumbered by physical weakness. God gives but also deprives at the same time, a mystery which humankind has not been able to solve. Fatherless when barely half-a-year old, he was verily a titan (like the character Gulliver he created) among pygmies (like the Lilliputians). He abhorred injustice and thought and prayed forever for the felicity of humankind. He lived to be 78, but contended on the basis of his experiences that the gift of a long life is bought at a very high price.

Laurence Sterne, the preacher-poet Yorkshireman, left behind several nuggets of wisdom in his novels and a couple of them can be cited hereunder:

“I laugh till I cry, and I cry till I laugh” (reminding one of the Yin and the Yang which feed into each other)

“Give me all the blessings of wisdom and religion if you will, but above all, let me be a man.”

Scott, Balzac, Dumas

Sir Walter Scott, while being a prodigy like Swift, also had to contend with physical disabilities like him. He tided over them marvellously, prudently, gallantly and tirelessly, en route to a knighthood and immortality in the realm of English literature. Dreamy Honoré de Balzac, obdurate and uncompromising, believed that man’s destiny and purpose in life was to “rise from action through abstraction to sight” – a deed-word-thought ascent in other words. “Life lies within us (spiritual), and not without us (material)”, he averred. He never got the glory he deserved when he was alive, and his soul perhaps got the peace it richly merited when fame showed up posthumously.

Athos, Porthos, Aramis and D’Artagnan – characters from The Three Musketeers, a novel by Alexandre Dumas which presents the facts of 19th century France through the medium of fiction – were known to school-goers in the 1970s and 1980s, like yours sincerely. Dumas, as the Thomases have noted, met praise with a shrug and insults with a smile – stoically in other words. However, he had a penchant for sarcasm and trenchant wit which were unleashed whenever required. “I do not know how I produce my poems. Ask a plum tree how it produces plums,” is verily a testimony to his transatlantic contemporary Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “All writing happens by the grace of God.”

Hugo, Flaubert, Hawthorne

Two Frenchman and a New-Englander American comprise this trio. Viktor Marie Hugo, of Les Misérables fame, was born in the same year as Dumas, and was regarded widely as the ‘Head’ of the 19th century to Abraham Lincoln’s ‘Heart’. His crests of hard-won success coincided with the troughs of ill-deserved sorrow (he had to contend with the deaths of his wife and children). The Divine Will strengthened his mind, soul and fingers to move quill on paper, enabling the much-bereaved Frenchman to cope and conquer. “Sorrow,” he wrote, “is but a prelude to joy.” A stoic would however add, “and vice versa”. Quite like Sterne’s “I laugh till I cry, and I cry till I laugh”. Despite all that he had to endure; Hugo always believed in God and the purposes he lays out for human beings in their lives.

Hugo’s friend Gustave Flaubert considered the written word to be a living entity, with a voice, perfume, personality and soul. A concoction of realism and romanticism, if ever there was one, Flaubert was also a peculiar amalgamation of poet-cynic, artist-scientist and humankind’s comforter-despiser. He ardently believed that though the soul is trapped within a mortal corpus on the terrestrial realm, it (which is the actual identity of a human being) lives in the idea-realm, and finds its rewards therein.

Hawthorne, on the other side of the ocean, was charmed by the sea and surf and sand in his childhood and youth, having spent a lot of time along the New England coast in north-western America. That led him to dwell on the mysteries of the human soul (which continue to be mysteries at the time of writing), while rebelling against the Puritanic influences that had engulfed the region. He was on an eternal quest, an intellectual and moral pathfinder in his own right, and a pioneering rebel with the pen and quill in his arsenal.

Thackeray, Dickens, Dostoyevsky

William Makepeace Thackeray, readers will be interested to know, was born in Calcutta (now, Kolkata). A sentimental cynic who glimpsed the stupidity of life through the fog of sorrow, he believed that foolishness of the past is a pre-requisite to wisdom in the present and the future – in other words, simply put, we learn from our errors as we move on. ‘Gifted with a bright wit and an attractive humour’, in the words of Charlotte Bronte, he contended that literature was more a misfortune and less a profession. His cynicism helped him to grasp reality, and feel empowered in the process –“How very weak the very wise; how very small the truly great are.” Kind and wise humans often lack the power to change things for the better, while the powerful ones lack the conscience, will and goodness to want to do so.

Thackeray rivalled with Charles Dickens for fame and glory. Dickens, similar to Scott and Swift, had to contend with physical discomfort in his childhood and adolescence, in addition to a father who was not responsible with the money he earned. These experiences would later feed into the stories he churned out prolifically; semi-autobiographical some of them, while informing readers at the same time about the times that prevailed – “the best of times and the worst of times” (A Tale of Two Cities). His humble beginnings made him burn the midnight oil later in life, fuelled by the ambition to succeed, which he sustained all along. Quite like it was Hugo across the Channel, the troughs of torment annulled the acmes of accomplishment. Yet, he remained grateful to God and fellow-humans for the life he lived, and bade one and all a ‘respectful and affectionate farewell’, before ascending to the astral realm.

Reclusive Feodor Dostoyevsky, like Hawthorne in America, struggled to shake off a Puritan upbringing and sought fodder for his literature among the common man – the suffering proletariat who visited liquor shops to drown their sorrows in alcohol. Man, he believed, was responsible for his own salvation…and not God. He however did believe at times that God saved those whom men punished. But then, he also contradicted himself or seemed to do so, when he said that man is saved only because the Devil exists. But perhaps that was not a contradiction after all – God saves man from what he has to be saved from! The meaning of life, according to Dostoyevsky, was the brute-to-angel and the sinner-to-saint transformation of man; quite on the lines of Balzac’s action-abstraction-sight prescription.

| Novelist | Lifespan | Selected works |

| Giovanni Boccaccio | 1313-1375 | Filocolo, Filostrato, Teseide, Fiammetta, Amorosa Visione, Ameto, Decameron, Life of Dante |

| Francois Rabelais | 1495 – 1553 | Pantagruel, Gargantua |

| Miguel de Cervantes | 1547 – 1616 | Galatea, Don Quixote, Novelas Exemplares, Persiles y Sigismunda |

| Daniel Defoe | 1661-1731 | The True-Born Englishman, The Apparition of Mrs Veal, Robinson Crusoe, The Dumb Philosopher, Serious Reflections, Moll Flanders |

| Jonathan Swift | 1667 – 1745 | The Battle of the Books, The Tale of a Tub, Gulliver’s Travels Children of the Poor, Directions to Servants, Polite Conversation |

| Laurence Sterne | 1713-1768 | A political romance, Tristram Shandy, Sermons by Yorick, The Sentimental Journey |

| Sir Walter Scott | 1771 – 1832 | The Lady of the Last Minstrel, Ivanhoe, Kenilworth, The Lady of the Lake, Waverley, The Monastery |

| Honoré de Balzac | 1799 – 1850 | The Country Doctor, Eugenie Grandet, Jesus in Flanders, Droll Stories, Louis Lambert, Seraphita, A Daughter of Eve, The Peasants |

| Alexandre Dumas | 1802 – 1870 | The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo, The Black Tulip, The Prussian Terror, The Forty-Five, Chicot the Jester, The Queen Margot |

| Victor Hugo | 1802 – 1885 | Les Misérables, The Toilers of the Sea, The History of a Crime, Legend of the Centuries, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Supreme Pity |

| Gustave Flaubert | 1821 – 1880 | Madame Bovary, The Sentimental Education, The Temptation of St Anthony, Bouvard and Pécuchet, Salambbô |

| Nathaniel Hawthorne | 1804 – 1864 | Twice Told Tales, The Blithedale Romance, The Scarlet Letter, Mosses from an Old Manse, The Marble Faun, Tanglewood Tales, The Snow Image |

| William Thackeray | 1811 – 1863 | The Great Hoggarty Diamond, Vanity Fair, The Book of Snobs, Henry Esmond, The Virginian, Lovel the Widower, The Newcomes |

| Charles Dickens | 1812 – 1870 | Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, Barnaby Rudge, David Copperfield, A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations |

| Feodor Dostoyevsky | 1821 – 1881 | Crime and Punishment, Poor Folk, The Double, The Landlady, The Family Friend, The House of Death, The Gambler, The Idiot, |

| Leo Tolstoy | 1828 – 1910 | War and Peace, Anna Karenina, Childhood, The Cossacks, Two Hussars, Three Deaths, A Confession, Master and Man, Resurrection, What is Art |

| Guy de Maupassant | 1850 – 1893 | Une Vie, The Ball of Fat, Mademoiselle Fifi, The Necklace, Yvette, Our Heart, Bel-Ami, Pierre and Jean, A Piece of String |

| Emile Zola | 1840 – 1902 | Doctor Pascal, Therese Raquin, The Dram Shop, Nana, Germinal, The Earth. The Dream, Rome, Paris, Fertility, Work, Truth, Justice |

| Mark Twain | 1835 – 1910 | Huckleberry Finn, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Joan of Arc, A Connecticut Yankee, What is Man, The Prince and the Pauper |

| Thomas Hardy | 1840 – 1928 | A Pair of Blue Eyes, Under the Greenwood Tree, Far from the Madding Crowd, The Trumpet-Major, The Mayor of Casterbridge, Jude the Obscure, Tess of the D’Urbervilles |

Tolstoy, Maupassant, Zola

Leo Tolstoy, also a Russian like Dostoyevsky, unlike Dickens, was not guided onward and forward by ambition. He believed in stooping to conquer and was motivated in his life’s journey by compassion. Orphaned when not yet a teenager, haunted by an inferiority complex pertaining to his ‘unprepossessing appearance’, and disgusted with organised religion (the Orthodoxy which prevailed in Russia), he discovered his purpose in Rousseau’s philosophy and in ridding the human heart of evil and helping it to live in peace, in communion with Nature. His dissent, rebellion and dissatisfaction with extravagance (of the nobility), bigotry (of the clergy) and tyranny (of the royalty), were the seeds, water and fertiliser for his contributions to Russian literature. Readers know that Mahatma Gandhi was inspired by the philosopher-prophet-penman Leo Tolstoy to set up the Tolstoy Farm in South Africa. Some nuggets which will serve as parts of vade mecums for readers:

“Death, blessed brother death, you are the final deliverance.”

“There are millions of human beings on earth who are suffering. Why do you think only of me?”

Guy de Maupassant was one of those millions who suffered a lot. Reading about the tragic short life led by him, with constant physical and psychological afflictions which led to autoscopy in his 42nd year, and death in the 43rd, makes one sad. It also makes readers turn to his short stories – of which he is known to be a master – more eagerly. Flaubert and de Maupassant knew each other well, the former being a ‘guru’ guiding the latter on from time to time, along his literary journey.

Another Frenchman – Emile Zola – a contemporary of de Maupassant and Flaubert and a good friend of the painter Paul Cezanne, progressed through pitfalls and serendipitous godsends to profile the poor people of France, and ironically rise to richness thereby. A man who defended justice and spoke up against all forms of unfairness, Zola is known for standing up for the French army captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jew who was wrongly (and knowingly so) accused of treason in 1894, and playing a key role in clearing the Jew’s name in 1906 (four years after Zola passed away). His last written words –“…to remake through truth a higher and happier humanity.”

Twain and Hardy

The man most readers know as Mark Twain, was born Samuel Clemens in America. Though it would not be right to compare and contrast the travails endured by the novelists profiled by Henry and Dana in this book, it can at least be said that a peep into Twain’s life tugs at your heartstrings and the vibrations linger on for a long time. Indeed, as a natural consequence, respect and admiration well up in the heart, for this novelist. He suffered an awful lot, but also learnt to laugh at his own agony as an ‘onlooker’ – the soul observing the pain of the body and the trauma of the mind it enlivens, from a distance, without being affected in any way. Like Hugo on the other side of the ocean, he endured what can be considered as possibly the greatest sorrow a man can face – burying/cremating his own children, one after another. Twain always supported the underdogs while voicing his disgust at the pompousness of the rich and powerful, in his own unique brand of sarcasm. The following words of his may sound cynical, but they are open to interpretation:

“Nothing exists but you. And you are but a homeless, vagrant, useless thought, wandering forlorn among the empty centuries.”

Without letting these words deter you, link them with the other sufferer Viktor Hugo’s “Nothing is as powerful as an idea whose time has come”, and soldier on.

The last of the twenty, Thomas Hardy, is yours sincerely’s favourite (I happen to read all his important works in my twenties, if I remember right). Hardy like his fellow-Britons Swift and Scott was born with a “frail body, strong mind and compassionate soul”. He was compassionate towards and appreciative of the forces and elements of Mother Nature – winds, clouds, bees, butterflies, squirrels, sheep etc., as pointed out by the Thomases. The manner in which he moulded his protagonists in his novels was catalysed by this compassion. Most of them are compassionate themselves, and evoke compassion in the hearts of readers, quite easily. Hardy wanted to teach his fellow-humans how to “breast the misery they were born to”, by using his fictional protagonists as instruments. His life was an exercise in “subduing the hardest fate” and “persistence through repeated discomfitures”. As it often happens with true geniuses, he was much ahead of his times, and the glory that illumined his soul in heaven posthumously, more than compensated for the disappointments which had to be endured when it was encased in his mortal corpus.

Not the last word by any means

Serendipity, it must have been, which made me stride into the Red Cross charity shop in Karlstad in June, wherefrom I purchased this 280-page treasure. To quote Longfellow (who incidentally was a college-mate of Hawthorne’s),

“Lives of great men all remind us/We can make our lives sublime/And departing leave behind us/Footprints on the sands of time.”

The 20 authors profiled in this book represent a huge family of writers who converted fiction from ‘a stepdaughter of the Muses’ to an ‘epitome of the philosophy of life’, except that there were no ‘daughters or stepdaughters of men’ listed among the novelists in this volume.

.

G Venkatesh (50) is a Chennai-born, Mumbai-bred ‘global citizen’ who currently serves as Associate Professor at Karlstad University in Sweden. He has published 4 volumes of poetry and 4 e-textbooks, inter alia.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International