Book Review by Basudhara Roy

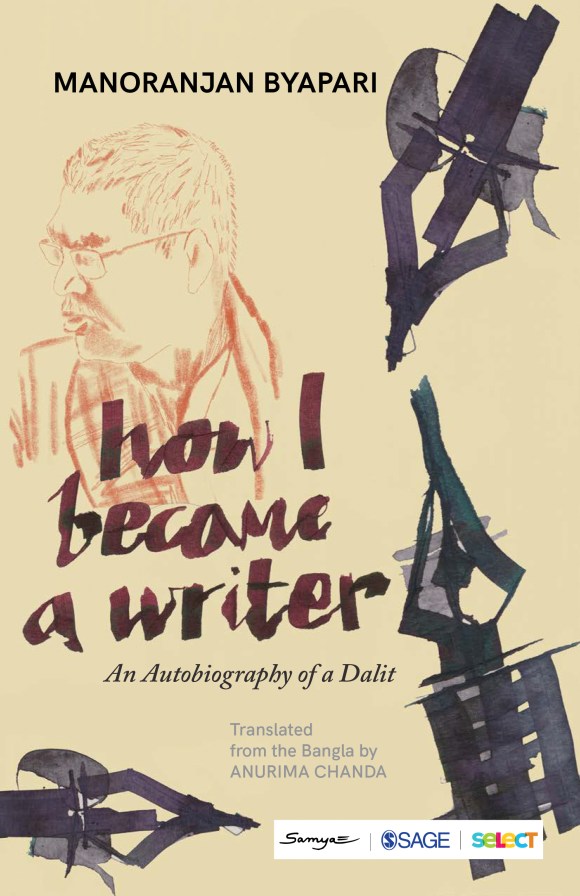

Title: How I Became a Writer: An Autobiography of a Dalit

Author: Manoranjan Byapari

Translator: Anurima Chanda

Publisher: SAGE Publications India and Samya under Samya SAGE Select imprint

The autobiography, as a literary genre, has a compound and far-reaching relevance. Among the many ways that it engages in a productive conversation with the world, is its staunch social impact. When and why does a person set out to write his or her life’s story? The answers to this could be numerous. Central, however, to each of them would be the perception of a threat to one’s experienced or imagined identity, the attempt to seize empowerment through the act of narration, and the identification of one’s individuality as having a widely referential social base that could encapsulate some meaning for humanity at large.

In the teeming, diverse and thoroughly spectacular life of writer, Manoranjan Byapari, an impulse towards all the three can be found. An unlettered rickshaw puller-turned indefatigable and award-winning fiction writer, and currently a member of the Legislative Assembly of West Bengal (Balagarh constituency) and the Chairperson of the Dalit Sahitya Akademi, West Bengal, Manoranjan Byapari’s How I Became a Writer: An Autobiography of a Dalit is the translation of the sequel to his Itibritte Chandal Jivan (Interrogating My Chandal Life) published in 2017 and winner of The Hindu Prize 2018 for non-fiction.

“I keenly believed that even though a life might be trivial, inferior or disgusting, there was something to learn from it which could come handy later. […] People who scavenged through dustbins would know that sometimes one might also find delicacies in the garbage,” writes the author (in the context of a particularly obnoxious character in the book), articulating a practical and philosophic doctrine that is hard to beat. If taken as a metaphor for his own life’s tireless trials, these words throw light on Byapari’s literary treatment of every little or mean episode in his life with sincerity, stubbornness and sagacity.

The sequel How I Became a Writer effectively takes off from where the first book ends – Byapari’s return to Calcutta from Dandakaranya and his taking up the job of a cook at the residential Helen Keller School for the Deaf and the Blind. Spanning a journey of around two decades, the book documents the arduous, painstaking, courageous and unrelinquishable labour of nurturing the ambition to write amidst the innumerable hazards-big and small-that threaten a Dalit’s dignified existence in India.

Comprising a series of thirty-four vignettes, the book is divided into two parts – ‘School Shenanigans’ and ‘The Right to Write’. The former section offers a close look at Byapari’s work-life – his workplace, duties, associates, and the systemic social inequities that are intended to steadily impoverish and dehumanize those who inhabit the lowest rungs of the class and caste hierarchies. The latter section focuses almost exclusively on his creative life, his intense literary and activist aspirations, and his relentless growth as a writer in the face of every obstacle to body, mind and spirit. The two sections, however, speak very intimately to one another with the result that they effectively build up one seamless narrative whole, animated, in each of its fibres, by “jijibisha” – the indomitable will to live that has characterised Byapari’s intellectual journey throughout.

In her ‘Foreword’ to the book, Sipra Mukherjee, the translator of Interrogating My Chandal Life, draws attention to the remarkable “non-marginality” of Byapari’s writing that, in the first part of his autobiography, exhibits and establishes itself in his choice of both language and geo-political space of creative exploration. In How I Became a Writer, Byapari’s marginal viewpoint on the history, narratives and psychology of the mainstream impresses further. His knowledge of the world is clearly staggering, his perception sharp, and his intuitive wisdom is matchless in its perspicacity. Alert, critical, and thoroughly versed in his Marxist epistemology, he understands the social dialogue of money and power and that of rights and denial, with deftness and insight. Most importantly, he is constantly aware of being not merely an individual but a representative of a social group – the proletariat who must attempt, by all means, to speak truth to power:

“Muttering furiously, she asked, ‘Royda asked you to make tea and you refused. Is that right?’

“I answered in the affirmative without an iota of tremor in my voice. I did what a representative of the working class would do had it been within the world of one of my own stories. The way Bordi, like one of the overlords, had called me forth to show off her positional power in front of her people, I too, was eager to show her that I was a knowledgeable and brave representative of my class of people.”

Throughout Byapari’s language, there is a quiet and determined authority intended to radically subvert the dense and intricate mainstream texts of injustice and victimization. One of his potent subversive tools is certainly his robust and well-toned satire, the other being his close reading of mythological material, folk tales, and indigenous wisdom located in anecdotes and proverbs. Bringing this local ontology and epistemology to bear on the mainstream knowledge involves a constant interrogation of the latter’s chosen socio-political and cultural texts, thus constituting a bottom-up view on social theory and praxis.

Glowing vividly in these pages is also Byapari’s unvanquished faith in literature as a means of social reform. He reiterates here, often, the necessity to take up the pen as a tool of protest, as a means of emancipation from indignity, and as the only method of scripting oneself into social discourse – “Somebody had said that a writer does not write with a pen, but with the spine.” But the act of writing which is often made to appear autonomous and independent of social interference, may not come as easily to everyone. To someone like himself, as Byapari insists, literacy itself has been a gift and the act of reading and writing, a liberation from his otherwise “insignificant, ugly and hateful life”.

In a society where writing has often been valorised as a private intellectual activity, Byapari strongly points out how privacy is, in itself, a privilege. Contrary to the fashionable notion of the writer as entitled to a ‘writing space’ both physically and temporally, Byapari’s autobiography projects him as accomplishing his writing in the oddest of spaces and hours, under the most threatening of conditions, and with the sole will to keep the fire in his soul alive. Both cathartic and revolutionary, his creative life becomes a valuable agency for him to wield his self-esteem against life’s diminishing forces.

But to be able to write and to, even, write well is not enough. To carve a niche for oneself in the writerly world, and to be heard and responded to is an enormous challenge in itself. There is, firstly, the significant handicap of financial investment in publishing a book; secondly, the apathy of prejudiced and non-discerning readers towards writers of the lower caste; and thirdly the entire nexus of publishers, marketing, reviewers and awards to negotiate with. To someone like Byapari, handicapped severely by both his caste and class, literary recognition has been very slow and unforthcoming.

It has, however, happened over the years, for as Byapari believes, in the world of literature, the way upward lies only through dedication, toil, perseverance, and the presence of an empathetic and like-minded literary community. But though the writer remains inordinately grateful for where he has arrived, there is also, at times in the book, a serious questioning of the practical outcome of meaningful literature in the world. Does it make a difference? Does it help transform the conscience of society? Does it lead to material improvement in a poor writer’s life circumstances? Byapari remains distinctly conscious of having been transformed from a writing person to a literary subject under the harsh glare of literary festivals, media and academics but his greatest fear of failure revolves around the possibility that his writing may have failed to make a dent on the world’s harsh indifference:

“Why did I even write? Would I be able to change this bloodsucking societal system standing atop the rotting thousand-year-old foundation with my pen alone? Would I be able to stop the inhumane religious brutality of the priestly class in the name of caste? The child lying on the footpath, who had curled up in the bitter cold, could I bring him a blanket? That child crying in his mother’s arms in hunger, would I be able to make him sit in front of a plate full of warm freshly made rice?

“I could not! I could not!”

However, as in the case of every true artist, Manoranjan Byapari’s love for writing triumphs over all misgivings. How I Became a Writer is a glowing celebration of his tribulations, grit, antagonisms, friendships and the generous support of many noble souls that helped pave his way to artistic maturity and fame.

For those who cannot read the book in Bengali, this translation by Anurima Chanda, an academic and translator, arrives as a coveted gift. Organic, fluid, and maintaining the right balance between linguistic and semantic authenticity, this animated rendering of Byapari’s life introduces readers of English to a writer who remains etched in memory as much for his lyricism and humour as for his sheer honesty and brilliantly satirical social criticism.

.

Basudhara Roy teaches English at Karim City College affiliated to Kolhan University, Chaibasa. Drawn to gender and ecological studies, her four published books include a monograph and three poetry collections. Her recent works are available at Outlook India, The Dhaka Tribune, EPW, Madras Courier and Live Wire among others.

.

Click here to read the book excerpt from How I Became a Writer

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles