Photographs and narrative by Suzanne Kamata

I felt some trepidation as I prepared to enter the United States from Japan. It would be my first time to return to my native country since the new administration took office. Rumour had it that immigration officials would check my phone for leftist activity on social networks (they didn’t). I’d heard about books being banned, libraries and museums being closed, and the words “diversity,” “equity,” and “inclusion” being suddenly prohibited in government documents.

My parents, originally from Michigan, in the North, live in South Carolina. This is where the Civil War began in 1861 when state legislators voted to secede from the union. They wanted to preserve slavery and allow its expansion into western territories. South Carolina and six other Southern states formed what was called the Confederacy.

The Confederate flag, a symbol, for many, of an ugly past, was first flown from a flagpole in front of the capitol building in 1961, in commemoration of the hundredth anniversary of the Civil War. It remained flying in protest of the Civil Rights movement, and was only taken down in 2017, after a twenty-one-year-old white supremacist entered a historically black church in Charleston and opened fire on a prayer group. He killed nine people and injured one. Now the flag is on display in a special room at the State Museum.

My visit to South Carolina coincided with a visit from my son, a student of history with a keen interest in politics. My dad thought it might be fun to take his grandson to the Statehouse for a tour. My son was enthusiastic about this idea. I went along, too, with some reservations.

We drove into the city of Columbia and parked in a public lot at the back of the Statehouse. As we entered the grounds, we came upon a statue of Strom Thurmond. He was a teacher, a lawyer, and a highly decorated soldier. He served as governor of South Carolina from 1947-1951, and as senator for 47 years after that, right up until his death at the age of 100. Until very recently, he held the record for the longest filibuster, which is a tactic used to delay voting upon a contentious bill. Basically, a senator takes the floor and keeps talking for as long as he possibly can. In August of 1957, Strom Thurmond gave a speech lasting 24 hours and 18 minutes in opposition to a law promoting civil rights. After his death, it was revealed that he had fathered a child with his family’s 16-year-old African American maid. Of course, that is not inscribed on the plaque at the base of the statue.

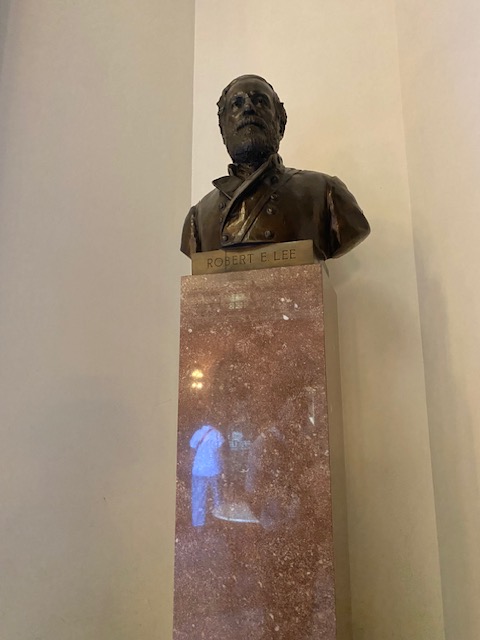

To be honest, I had expected to see this statue, as well as other monuments devoted to Confederate generals and segregationists. But I was pleasantly surprised to find a new monument commemorating the accomplishments of South Carolinian African Americans.

We went inside the building and were ushered to a room off to the side for a short film before the tour began. I noted that the film was narrated by a young African American man, which seemed like a nod to diversity, equity and inclusion. He mentioned, perhaps with false pride, that Strom Thurmond held the record for longest filibuster in the history of the United States. Nevertheless, I was glad to see that the film highlighted the achievements of women and minorities, such as South Carolina’s first – and so far, only – female governor, Nikki Haley, the one who ordered that the Confederate flag be removed from state grounds.

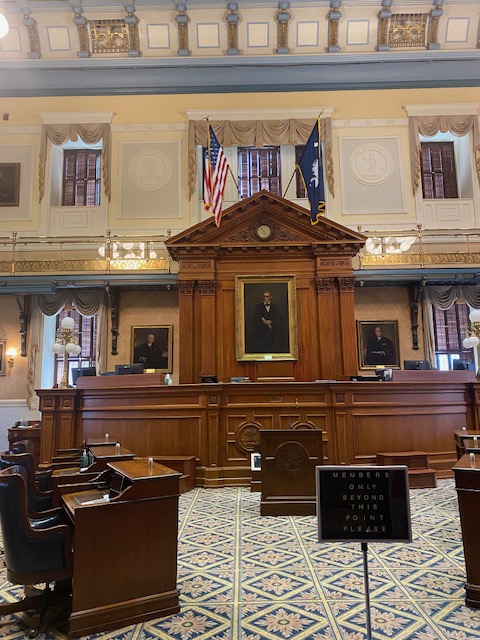

During the rest of the tour, I breathed a bit easier, admiring the intricate ironwork on the stair railings, and the stained glass above the chambers. I enjoyed hearing that Magdalen Feline, a woman goldsmith had crafted the symbolic mace, which is placed in a rack at the front of the Speaker’s podium when the House of Representatives is in session. And I was pleased to see a portrait of African American educator, philanthropist, and civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune (1875-1955) prominently displayed.

South Carolina is a complicated state, and this is an increasingly complicated world. However, going on this tour gave me hope that my fellow Americans might get back to celebrating diversity, equity, and inclusion, and all of the best parts of human nature.

Suzanne Kamata was born and raised in Grand Haven, Michigan. She now lives in Japan with her husband and two children. Her short stories, essays, articles and book reviews have appeared in over 100 publications. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize five times, and received a Special Mention in 2006. She is also a two-time winner of the All Nippon Airways/Wingspan Fiction Contest, winner of the Paris Book Festival, and winner of a SCBWI Magazine Merit Award.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International