Narrative and photographs by Suzanne Kamata

My daughter Lilia and I were in Wakayama Station, on our way to see the cat station master in the small town of Kishi. Because Lilia uses a wheelchair, we had to ask for assistance getting on and off the train.

“What time are you coming back?” a Japan Railways employee asked. They would have to prepare for our return later in the day.

“We want to come back on the Tamaden,” I said, referring to a train with a cat theme. I had taken a photo of the train schedule, and I opened my phone to check the time. It was now about twelve-thirty. Although there were trains every thirty minutes – the Animal Train, the Plum Train, the Cha Train – the Tama Train (aka Tamaden) only ran from Kishi twice a day. The next would be at 2:38, which wouldn’t give us much time to see everything. We didn’t want to rush. The final one would be at five fifteen.

“Five fifteen,” I said.

The man gave me a dubious look. “There isn’t very much to do in Kishi,” he said. “There’s nothing there. Are you sure you want to stay that long?”

What about the café? The museum? The shrine? The cat? We had come all this way, and we would only be there for a couple of hours. If we ran out of things to do, we could go for a walk. It was a lovely day, after all.

“You want to ride on the Tama Train, don’t you?” I asked Lilia.

“Yes,” she replied.

“What if we change our minds and want to come back early?” I asked the JR attendant.

He told me that would be difficult.

“Okay, then. Five fifteen.”

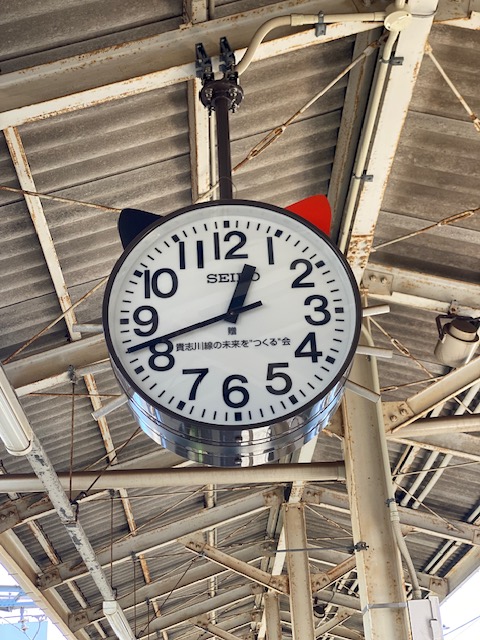

After showing our tickets, we were given Wakayama Electric Railway Kishigawa Line postcards. On the platform, there was a rubber stamp featuring a cartoonish Tama, with Wakayama Castle, and citrus fruits in the background. Little blank books meant for collecting stamps from various places were sold in gift shops. We didn’t have such books, so we stamped our postcards. A clock with cat ears – one black, one brown, like a calico – hung overhead.

I deduced that the train on the tracks, decorated with colored hearts, illustrations of dogs and cats, and the letters JSPCA, was the Animal Train. Other than the banners featuring cats clutching flowers and a white dog holding a bone, the inside of the car was ordinary. Like most Japanese trains, it was clean, with plush benches along each side, and an orange ticket dispenser at the entrance and exit.

Lilia marveled at how empty the train was. Now that she lived in Osaka, she had become a city girl, used to being squished between passengers on her morning and evening commutes. I was pretty sure that most of the people getting on board were tourists on their way to see Tama.

During the thirty-minute ride, the train swayed on the tracks, past rice paddies, and orange orchards.

“Maybe in the future they will make it easier for people in wheelchairs to visit,” I said.

Lilia frowned and made the sign for money. Yes, it might cost a lot to add an elevator in the station, but was it really too much to ask?

At the end of our journey, which was also the end of the line, a young man wearing white gloves laid out the ramp. Again, we conferred about what time we would go back. He gave me a paper schedule, folded into the size of a credit card, and showed me the phone number at the bottom.

“If you change your mind about what time you want to go back, just call this number,” he said.

“Thank you.” I looked around. We were indeed in the middle of nowhere. Yes, there were many houses, but I could already tell that the station itself was quite small, and, as the attendants in Wakayama had said, there weren’t any shops and restaurants around. But there were quite a few people, many from abroad. I saw a young woman in a pink hijab, and a group of Chinese tourists.

We paused before the shrine to the original cat station master, Tama, on the platform, then went down a ramp, and to the front of the station. By now, we were hungry. But first, the cat.

On this day, Yontama, a calico like her predecessor, was in a little room behind glass at the side of the station. She was napping on the wooden floor, next to a soft, plush mat. Many people were taking photos of her, but no one was bothering her. She wasn’t wearing the hat or suit of a stationmaster or doing anything special. She looked – and I say this with love – like an ordinary cat.

To the left of the window stood a fortune dispenser. Lilia dropped a hundred-yen coin into the box and extracted a rolled-up piece of paper. She unfurled it and showed it to me: “Very happy!”

“Great!” I gestured to the café behind us. “Now let’s go eat.”

We entered the Tama Café, which also seemed to function as the museum. The original cat station master’s hat, decorated with a strawberry emblem, a lace-trimmed blue velvet cloak worn by Tama, and various framed documents were displayed in a glass-fronted cabinet.

I ordered two Hot Cat Sets for us — fish sausages on hot dog buns, strawberry sodas, and cookie wafers printed with Tama’s image. We topped that off with green tea floats, with a scoop of green tea ice cream with almond ears and chocolate chip eyes.

After we had finished our meal, we visited the gift shop next door. From there, we could see Yontama from a different angle. She was awake but still lolling about. I bought little Yontama towels, which are always used in Japan for blotting your hands dry after washing them in public places. Then I paid for a fortune of my own. “Very happy,” it said. I wondered if all of the fortunes in the box were exactly the same.

Across the street was a tourist information center. Despite the JR employees’ skepticism, the people of Kinokawa City had taken the time to consider ways to occupy and engage the many visitors who would come to see the cats. Brochures in many languages were arranged in a rack. I plucked a few and discovered that a beautiful park dating back to the medieval period was within walking distance. The region also produced a lot of fruit, such as strawberries, figs, and oranges.

“Shall we go for a walk?” I asked Lilia.

She nodded. Using a map app on my phone, we set out for Hiraike Park Land. Part of the walk was uphill. Although Lilia’s wheelchair was electric-assisted, she still had to turn the wheels. Her arms started to get tired, so I helped her out for some of the way. We passed fields of cabbages, rice paddies, and groves of lemons, oranges, and figs. Unattended farm stands offered clear plastic bags of freshly picked persimmons and citrus fruits at bargain prices, much cheaper that those sold at the supermarket back home.

We finally arrived at the park. We stopped to observe the ducks and herons, the placid blue pond. According to the map, some ancient burial mounds, made distinctive by their key-holed shape, were nearby. I thought that we might be in danger of exhausting the wheelchair’s battery, however, so we didn’t go in search of them.

On the way back to the station, I stopped at one of the farm stands, put a couple of coins in the money box, and bought a bag of oranges. I would take it back as a souvenir for my husband and me to enjoy.

At one point, Lilia stopped, threw back her head and looked at the sky. “Ao,” she said in Japanese, drawing her fingers across her cheek in the sign for “blue.” She signed that there were no clouds. Indeed, it was a perfect autumn day.

When we were almost to the station, Lilia spotted a general store. She wanted to go inside, so we did. The lone woman behind the counter did not greet us, as is customary in Japan. I wondered if she was put off at the sight of a couple of foreigners. Of course, my daughter is half-Japanese, and has spent her entire life in Japan, but when she is with me, people assume that she is from abroad.

At the front of the store, school uniforms were displayed on mannequins Further inside, various goods were haphazardly arranged – a rack of flannel shirts, a shelf of liquor bottles, snacks for kids dropping in after school. It looked like the aftermath of a rummage sale. When Lilia started down a narrow aisle in her wheelchair, the woman drew in her breath. I could sense her fretting behind us, but she didn’t say anything. What must it be like for these country people to deal with the many foreigners traipsing through their small town? I was reminded of how people in Tokushima, where I live now, used to literally tremble when they saw my foreign face and thought that they might have to speak English.

Lilia decided to buy a packet of shrimp chips. The woman took her money, thanked her, and we got out of her hair.

Back at the station, we returned to the gift shop. Although Yontama was on the clock until four, and it was past four thirty, she was still relaxing in her little room. She probably didn’t mind. No one was tapping on the glass or otherwise harassing her. She had a good view of tourists buying cat themed T-shirts, cookies, and keychains. Lilia bought an ema, a small wooden plaque on which she would write a wish, and appeal to the cat deity, Tama Daimyojin.

We went onto the platform, and I tied Lilia’s ema onto a wooden board, along with wooden plaques inscribed by people from all over the world: “Wishing happiness and peace to animals all around the world.” “May all the strays and rescues get a good and loving home.” “May Pomelo, Walnut, and I live a long healthy life together.”

Dusk was already falling. The platform began to fill with other visitors, who apparently had the same desire to ride the Tama Train as we did. A young Chinese woman with flowing bleached-blonde hair in Lolita-meets-Little-Bo-Peep fashion – bonnet, and a tiered plaid dress with frills, eyelet, and ribbons — posed while her friends took photos. I wanted to take her picture, too, and post it on my Instagram account. She probably wouldn’t have minded, because she seemed to be some kind of influencer, but my daughter frowned and shook her head when I indicated my intentions.

As the train finally approached, everyone tried to get the best spot on the platform for the best shot. The front of the train was painted with a cat’s face. The windows served as eyes, and just below were a nose and whiskers. Cat’s ears were affixed to the top of the car. Pawprints and a cartoon version of Tama in various poses illustrated the sides. Inside, passengers could sit on colorful Tama-themed sofas.

Our friend from earlier showed up with a ramp, and helped us get onto the car with a space for wheelchair users. Lilia was delighted to find a bookshelf stocked with cat-related manga in the car. I handed her a stack of them to read over the duration of the train ride.

Although many of those onboard were obviously tourists, like the young Chinese women continuing their photo shoot, I realised that this train was also used by the residents of the towns on the Kitagawa Line. Observing a man in a business suit who appeared to be among them, I wondered what it was like for him to share his commute with eccentric travelers. I suppose it would be entertaining. At any rate, I couldn’t help but be impressed by this small town’s ability to create a new identity for itself and capitalize on it.

We returned to Wakayama Station tired but satisfied at having completed our mission. When I reached home, my cats were there to meet me, yowling and needy.

.

Suzanne Kamata was born and raised in Grand Haven, Michigan. She now lives in Japan with her husband and two children. Her short stories, essays, articles and book reviews have appeared in over 100 publications. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize five times, and received a Special Mention in 2006. She is also a two-time winner of the All Nippon Airways/Wingspan Fiction Contest, winner of the Paris Book Festival, and winner of a SCBWI Magazine Merit Award.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International