Book Review by Udita Banerjee

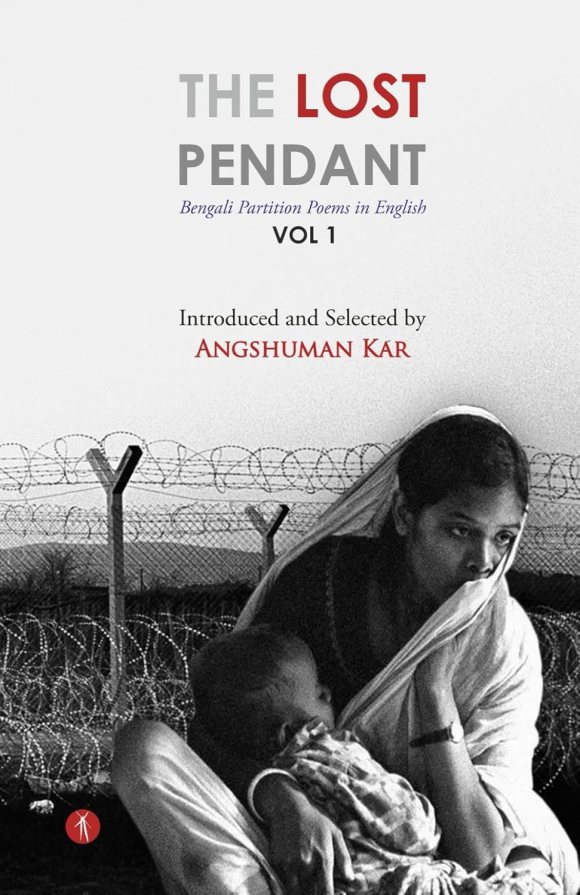

Title: The Lost Pendant

Editor: Angshuman Kar

Publisher: Hawakal Publishers

The Lost Pendant brings together poems translated from Bengali by translators such as Himalaya Jana, Mandakranta Sen, Rajorshi Patronobish, Sanjukta Dasgupta, Angshuman Kar, and Souva Chattopadhyay. Through these compelling translations, the volume makes a significant intervention in Partition literature, arriving at a moment when revisiting the lingering spectres of the event has become especially urgent. The Partition of India in 1947, which divided the subcontinent into India and Pakistan, resulted in one of the largest mass migrations in history and left enduring scars of displacement, violence, and fractured identities. As the editor, writer and academic, Angshuman Kar, notes in the book’s introduction how Partition remains a 78-year-old wound that continues to bleed.

The anthology showcases poetry from the eastern parts of the subcontinent, chiefly Bengal, Assam, and Bangladesh, featuring works by 41 poets from India and Bangladesh. Kar does not simply compile these poems but thoughtfully curates them to reveal several critical nuances. He invokes the concept of “buoyant memory,” introduced in his earlier work, Divided: Partition Memoirs from Two Bengals, to depict how “forgetting the past is impossible for the direct victims of Partition.” He also draws attention to the disproportionate representation of upper-caste Hindu Bengali poets, in contrast to the relative invisibility of Muslims and those from marginalised communities. This imbalance extends to gender as well, with a noticeable disparity between male and female poets in the collection.

The book is structured in two parts, respectively featuring poets from India and Bangladesh. The Indian section is notably larger and presents a wide range of emotions, reflecting both the immediate trauma of Partition and its long-lasting reverberations over the years. Many of the poems in this section express a deep nostalgia for a lost homeland. For instance, Alokeranjan Dasgupta’s ‘Exile’ evokes memories of abandoned spaces. Similarly, Ananda Sankar Rai’s ‘The Far Side’ laments the estrangement from what was once familiar. He writes, “Once it was a province, now an alien land / where you must enter passport in hand.” Basudeb Deb’s ‘Picture of My Father’ constructs a powerful portrait of the nation through the figure of the father: “Swadeshi movement war sirens famine flood / Riot and partition written in the wrinkles on his forehead.” After the father’s death, only a walking stick remains. The poem draws a powerful parallel between the futility of the father’s dismissive words, “This country is not a pumpkin that you can cut it in one blow”, and the uselessness of the walking stick after his passing. This object comes to embody the spirit of the deceased father, “just another old toy”, offering a stark commentary on how individuals became pawns in the hands of the state.

Several poets in the anthology focus intensely on the experiences of refugees, capturing both their suffering and the complexities of their identities. In ‘The Refugee Mystery’, Binoy Majumdar laments the loss of linguistic roots, noting how “the Bangals now speak the dialect of Kolkata all the time, having forgotten the dialects of Barishal and Faridpur / The Moslems of Dhaka are heard singing and speaking in the radio with the lilt of Uluberia.” His reflections emphasise the deep connection between language and social identity. This theme finds a resonance in Sunil Gangopadhyay’s poem ‘That Day’, where he writes, “On one side they named the waters Pani / on the other side–Jol.” Through this simple yet evocative contrast, Gangopadhyay underscores how a shared concept can be articulated through divergent linguistic expressions in India and Bangladesh, which become subtle yet potent markers of socio-linguistic divisions. Such poems provoke profound questions: Can the adoption of a new dialect truly redefine one’s identity? How does one navigate the tension between past and present linguistic selves, and is reconciliation even possible?

Viewed through the intertwined lenses of faith and suffering, poetry often functions as a repository of collective memory and a means of resilience. In this regard, Devdas Acharya’s three poems present a poignant exploration of the lived experiences of refugees in post-Partition India. A recurring and haunting image emerges in his work: a grieving father, who has recently lost a child to hunger, standing before a deity symbolically embodied by a swadeshi leader. This image encapsulates both the profound deprivation endured by displaced communities and their simultaneous reliance on unshaken faith. Despite the magnitude of loss, what sustained many refugees was a deeply rooted belief system that imbued their suffering with meaning.

By foregrounding the gendered dimensions of violence, Partition poetry exposes how women’s bodies became contested sites of power and trauma. In “She, on the Platform of a Station”, Krishna Dhar powerfully captures the plight of women during Partition. She writes, “Chased from the other side of the border, escaping fire and the fangs and tongues of wolves, one day she arrived,” evoking the image of a refugee woman doubly marginalised– “devastated by Partition” and simultaneously “dodging the eyes of the hyenas.” Here, the metaphorical wolves and hyenas represent predatory men who treated women’s bodies as extensions of territorial conquest. Kar points out in the introduction that very few women wrote poetry about their Partition experiences, largely because they were already engaged in the broader struggle for gender equality. While women’s memoirs on Partition exist, poetry by women addressing these themes, particularly from the 1970s, is strikingly limited. This absence is significant, as women’s experiences are crucial to understanding how deeply gendered the space of the subcontinent was during and after Partition.

Following independence, conflicts often emerged within the nation, revolving around issues of region, language, religion, and ethnicity. In ‘The Diary of a Refugee’, Shaktipada Brahmachari reflects on his sense of belonging across borders, juxtaposing his memories of a past home in Bengal with his present life in Assam. He writes, “The world is my home now, in Bangla my love I spell–Prafulla and Vrigu are the cousins of my heart,” referencing two leaders of the Asom Gana Parishad. While refugees in Assam experienced a more complex form of marginalisation due to ethno-linguistic differences, Brahmachari portrays a gradual process of acceptance, where both the homeland he left and the land he adopted come to hold emotional significance.

Across the border in Bangladesh, the theme of displacement persists. In “Leaving Home”, Jasimuddin asserts, “this land is for Hindus and Muslims,” calling on educators to return and “build the broken schools once more…we will find out our beloved brother, whom I lost,” a poignant appeal for reconciliation and return of Hindu families displaced by Partition. The motifs of memory and loss recur throughout most of these poems, a trope common between both the nations. This sense of finality is further echoed in Binod Bera’s lament: “Our nation is now three, all three are independent, and love lives an alien existence.” The emotional chasm created by Partition, and the subsequent loss of mutual affection, renders any notion of return futile.

The collection deserves commendation for its ambitious effort to recover voices from Bengali literature and render them accessible to a global readership beyond linguistic boundaries, through gripping translations. It is the first-ever translated collection of Bengali Partition poetry that captures the angst of the original poems with perfect nuance. The very title, The Lost Pendant, merits particular attention, for it resonates with themes of liminality and the fractured sense of identity experienced by the refugee poet Nirmalyo Bhushan Bhattacharya, better known by his pseudonym, Majnu Mostafa. Born in Khulna, Bangladesh, yet spending much of his life in Krishnanagar, India, Bhattacharya embodies the dislocation and dual belonging of Partition’s afterlives. As Kar insightfully observes, the choice of pseudonym can be read as a deliberate act of defiance, “a strategy to cross the boundaries set up by religious politics and fundamentalism–a move much needed in the subcontinent of our times.” In this sense, The Lost Pendant is not merely an anthology but a work of cultural recuperation as it attempts to resurrect poets whose voices risked erasure, while simultaneously protecting their oeuvres from the twin threats of historical amnesia and linguistic inaccessibility.

.

Udita Banerjee is an Assistant Professor of English at VIT-AP University. Her work has previously been published in platforms such as Outlook Weekender, Borderless Journal, Indian Review, and Poems India.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International