Suzanne Kamata shares a story from 1999, set during Obon or the Festival of Bon, a Japanese Buddhist custom that honors the spirits of one’s ancestors.

My husband is dancing.

The name of the dance is “Awa Odori,” “Awa” being the ancient name for Tokushima, where we live now, and “odori” being Japanese for “dance.” Its origins are unclear. Some say fertility rites, others claim it is a celebration of a good harvest.

My husband is thinking about none of these things as he dances with his friends of fifteen years. No doubt he is drunk on beer and fellow feeling, absorbed in the revelry of this annual festival.

I am at home alone in our apartment.

I could have gone, too, but I declined by way of protest. I’m demonstrating because while I am welcome to, indeed expected to, celebrate Japanese holidays, my own country’s holidays go ignored. When I’d wanted to do something special a month ago in observance of the Fourth of July, Jun had refused. “This is Japan,” he’d said, as if that would explain everything.

When I married Jun, I’d had a concept of international marriage as the combining of two cultures, not the elimination of one. True, I’d expected compromises, but on both sides, not just mine.

This time, however, I’m not giving in. I’m not going to budge. I didn’t go with him to visit his ancestors’ graves, and I am not going to don a cotton yukata[1] and dance in the streets to flute and drum. If he won’t see me halfway on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Independence Day, then I’ll just sit this one out.

.

During Obon, the whole family usually gathers at some point. I’ll admit that I did go along with Jun to his parents’ house where his sister Yukiko and her family, his aunts and uncles and cousins, and his grandmother were assembled.

Uncle Takahiro said, “Hello. How are you?” in English, and everyone laughed as if he’d just told a joke.

I answered politely in Japanese, then my husband’s sister pushed her three-year-old toward me. “Go ahead. Say it, Mari-chan,” she said, beaming with motherly pride.

Dutifully, Mari recited the litany of English words that she had learned since I last saw her: “Horse. Cow. Pig.”

Yukiko looked to me expectantly, and I indulged her with words of praise for her daughter.

I can see it now. Yukiko will be the worst kind of “education mama,” as they call mothers who obsess over their children’s school performances.

“They’re teaching English at Mari-chan’s nursery school now,” Yukiko told me. “A foreigner comes once a week.”

Then, unbidden, Mari launched into a song. It was “Eensy Weensy Spider,” complete with gestures. Though she garbled some of the words, she earned a hearty round of applause from the adults.

.

Even after all this time, Jun’s relatives still don’t know how to talk to me. I make them uncomfortable, and sometimes I feel that I should apologise for being there, or better yet, just disappear. They have never tried to talk to me about everyday things like popular TV shows, bargain sales at Sogo, the big department store in town, or new recipes. When conversation is flagging, someone usually says to me, “Don’t you miss your home? Isn’t it hard being so far away?”

“It’ll be different after you have children,” my friend Maki said. “They’ll accept you then.”

Maybe so, but it looks like children are a long way off for Jun and me. Although we have been married for seven years, we have no kids. Mari was born just nine months after Yukiko and her husband were married. Their second baby – a boy – came along a year later.

We want children. We have even tried. I know that there’s nothing wrong with my body because I’ve been to specialists all over town, but Jun doesn’t seem interested in getting checked himself.

His mother would never believe there was a problem with her son. I’ve heard her whispering with Jun’s grandmother. “It’s because she’s American.”

Jun’s grandmother, who doesn’t know any better, nodded her head and said, “Ahh, yes. I’ve heard that gaijin don’t keep the baby in the womb as long as we Japanese do. Gaijin and Japanese can’t make babies together.”

And Jun’s mother, who should know better, nodded her head and said, “Yes, yes. You may be right.”

My mother-in-law also tells Jun’s grandmother that I’m a lazy wife. She tells the story in a whisper loud enough for me to hear that sometimes when she drops by our apartment, Jun is loading the clothes into the washing machine! Another time, he was standing at the stove with an apron on, cooking dinner!

“He should have married a Japanese woman,” Jun’s grandmother says. “A Japanese woman would take care of him.”

.

Jun and I sleep together in the same bed. His sister sleeps apart from her husband, in another room entirely, with her two children. His parents sleep in the same room, but one of them sleeps in a bed, the other in a futon spread on the floor.

Just before we got married, we bought furniture for our apartment. At that time, Jun suggested getting separate beds. He said that it was practical. With two beds, there would be no tussling over sheets, no accidental kicking in the night. I cried because whenever I had thought about marriage, I’d had an image of us sleeping in each other’s arms, breathing in unison.

Finally, we got one bed, a “wide double” that we cover with a double wedding ring quilt. It’s true that sometimes one of us winds up wrapped in all the sheets while the other one nearly freezes, and sometimes I find myself pinned into an uncomfortable position by Jun’s heavy limbs, but I don’t care. For me, one of the great joys of this life is waking up close to him, close enough to kiss him and run my hand over his bare chest.

.

Jun likes carpet and sofas and colonial style houses. I have always admired the simplicity of tatami mats and just a few cushions to sit on, rooms enclosed by sliding paper doors. My ideal room is an empty one, totally void of any unnecessary object. From studying home decorating magazines while in the US, I’d come to believe that in Japan this minimalism was typical. When I got here, I found that that wasn’t true at all. Tiny spaces were crammed with every imaginable appliance, Western furniture, and tacky knickknacks from other people’s vacations.

Jun likes to live in the Western mode. Like most people of his generation, he rejects tradition, or says he does. He sometimes rejects Japan, but he will never leave this place.

He watches CNN via satellite, eats popcorn and s’mores and coleslaw. He sleeps in a bed and sits on a sofa and he’s married to me, an American.

Sometimes, when he’s tired or angry, he forgets that this is an international marriage. He says, “Why can’t you be more Japanese?”

I look at myself in the mirror and see what others see: my blonde hair, blue eyes, and white skin. I can’t help but laugh. “Because I’m not Japanese,” I say. Even if I changed my citizenship, changed my name, and acted exactly like a Japanese woman, people would still look at me and say “foreigner.” Even if I dyed my hair black, got a tan, wore contact lenses, and had plastic surgery, they would still be able to tell the difference.

At times like these, I look at Jun and say, “If you wanted a Japanese wife, then why did you marry me?”

And he always replies in the same way. “Because I love you.”

.

My friends Maki didn’t marry for love. She chose her husband in the same way that I chose a college, poring over applications and photos. She invited me to help her pick one out. I was puzzled by this process. I watched the reject pile become higher and higher and I felt sorry for all those men whom Maki didn’t want to meet.

“This one’s too short,” she said, tossing an application aside.

The next one she picked up went into the “no” stack as well. “He’s handsome, but I don’t want to marry a farmer. Farmers’ wives have to work in the field all the time.” She wrinkled her nose and studied her manicured fingernails. Her hand had never known hard work.

The few who went into the other pile had good jobs with decent salaries, respectable families, and compatible hobbies.

At first, I imagined that all of those men were clamouring to marry Maki, but then she told me she’d never met any of them. The profiles had been passed along by a matchmaker. Those men were probably going through pictures of women, too, picking and choosing, making little stacks.

I thought about all the things that had made me fall in love with Jun – things that you can’t tell from a photo or a piece of paper, like the sound of his voice and the sweet strawberry taste of his mouth. I asked her if any of that mattered.

“You fall in love after you get married,” Maki said. “You Americans think that life is like a fairy tale, and then you get a divorce when you find out you were wrong.”

Maki has been married for two years and has one child. She is still waiting to fall in love with her salaryman husband. She doesn’t complain, though. He works for a good company, and she can stay home with their baby or go shopping whenever she feels like it. Sometimes she whispers to me about the possibility of having an affair with an American man.

I have known Maki for four years. When I met her, she was working for a travel agency and struggling to master English. I gave her private lessons which eventually metamorphosed into coffee klatches and late nights in discos. She is sometimes irreverent and wild and I can’t help but like her.

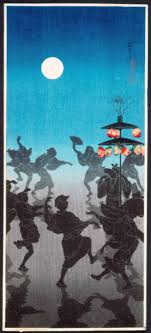

I can hear the chang-cha-chang-cha-chang of the festival music, a rhythm that never ceases or alters during the dance. I can picture the scene in my mind. The women are in yukata with hats that look like straw paper-plate holders folded over their heads. They wear white socks with the big toe separate, and geta, those wooden sandals. The men don’t wear any kind of shoes, just the tabi – the white socks, that will become soiled from the streets. They wear white shorts and the happi coats that brush over their hips. They tie bands of cloth called hachimaki around their foreheads.

The women dance upright, their hands grasping at the air above their heads as if they are picking invisible fruit. With each step, they bend a knee and touch a toe to the pavement, the thong driving between the toes and causing pain.

The men’s dance is freer and sometimes women deflect and join them. They dance bent over, arms and legs flailing. Their movements become wilder as the evening wears on. The dancers become more drunk, the music continues as before. Chang-cha-chang-cha-chang.

.

When I was a kid, we used to have big family picnics on the Fourth of July. My uncles and father and older male cousins played horseshoes, then later everyone would join in a game of volleyball. There was always too much food, and after gorging on fried chicken, potato salad, chocolate cake, and watermelon, we would hold our bulging bellies in agony. Then some of the adults would lie down and take naps while my cousins and I poked around in the creek, catching frogs and other slimy creatures.

As soon as dusk fell, and sometimes before, we would light sparklers under the close supervision of an adult. We waved them in the air, describing circles with crackling sparks, our faces full of glee.

Later, we’d all climb into my uncle’s station wagon and drive to the riverside to watch the real fireworks. Before the display began, the American flag was raised in a glaring spotlight and “The Star Spangled Banner” blasted out of loudspeakers. We all sang along, impatient for the show to begin. It always started out with small single-coloured bursts, like chrysanthemums or weeping willows in the sky. Then the fireworks got bigger, turning to rainbow blossoms worthy of our wonder. The adults oohed and ahhed and we said, “Wow! Look that that!” The very last was red, white and blue, and image of the flag we’d sung to earlier. Its shape hung in the sky for just a moment before falling like fairy raindrops.

During Obon, there are fireworks, too, but when I see them it’s not the same. I feel a tightening in my chest and the tears well up behind my eyes.

I go to a store nearby, one of the few businesses open during the holidays. The woman at the cash register greets me and smiles when I walk in the door. I wonder if she’d rather be dancing, and if she has been left behind while her husband parades in the streets.

.

I pick up a set of sparklers which are on sale and put them in a basket. I add a cellophane-wrapped wedge of watermelon. This one-piece costs more than the huge oval melons you can buy roadside where I come from. Into the basket also goes a package of frozen microwavable fried chicken and canned potato salad.

I pay for everything and go back to the apartment to prepare my feast. Night has already fallen. By the light of the overhanging kitchen lamp, I eat my chicken and potato salad. It’s the best meal I’ve had in a long time.

Later, when the dishes are done and drying on the rack, I take the package of sparklers and a box of matches onto the balcony. I light them one by one and watch them burn brightly in the darkness. I draw figure eights in the night air, write my name, etch zigzags of light.

When I’m finished, I lean over the railing and start to sing. I belt out “The Star Spangled Banner,” “America, the Beautiful,” and “I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy.” My voice is so loud that a dog starts to howl.

I feel better. I go back into the apartment and push the kitchen table to one side. With my back straight and my elbows bent, I reach up as if I am about to pick an apple from a tree. There is a smile on my face as I start to dance. Chang-cha-chang-cha-chang.

Takahashi Hiroaki (Japan, 1871-1945). From Public Domain

[1] A casual, unlined cotton kimono

Suzanne Kamata was born and raised in Grand Haven, Michigan. She now lives in Japan with her husband and two children. Her short stories, essays, articles and book reviews have appeared in over 100 publications. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize five times, and received a Special Mention in 2006. She is also a two-time winner of the All Nippon Airways/Wingspan Fiction Contest, winner of the Paris Book Festival, and winner of a SCBWI Magazine Merit Award.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International