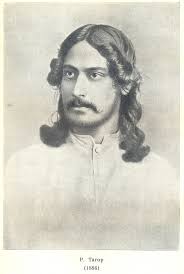

As the author of Jorasanko and Daughters of Jorasanko, which map the life of the greatest visionaries of the world, Aruna Chakravarti gives us a brief summation of the genius of Rabindranath Tagore.

Rabindranath Tagore was born in 1861 in the throes of the Bengal Renaissance. A unique movement which took place during the latter half of the nineteenth century, it saw the germination and the slow stirring into life of a social and religious consciousness and the emergence of a middle class that idealised British rule and used its support to usher in considerable social change. The revolutionising of values and the social, political and literary awakening that followed gradually came to encompass the whole of India.

The Bengal Renaissance, like its European counterpart, swung precariously for a while, between two worlds. One old, decrepit and dying by degrees — the other struggling to be born. A host of great personalities emerged during this time; household names to this day.

All were protagonists engaged in battle. Some to keep alive and perpetuate the old; some to hasten its death and bring about the birth of the new. Needless to say, it was the latter who prevailed. Bengal saw an upsurge of activity, the like of which had never been seen before, in fields as diverse from each other as politics and religion to literature and the performing arts. In this, Bengal’s close contact with the British served as a catalyst.

Yet the same movement, in its latter years, saw the first stirrings of resentment against British domination. India’s acceptance of English education and her faith in the scientific discoveries of the West was countered by a new revivalism. An assertion of political independence and the growth of a nationalist consciousness. A need for introspection became the call of the hour. Rabindranath was among the first to articulate this need. In an essay, entitled Byadhi-o-pratikar[1]written in the early years of the twentieth century Rabindranath expressed his doubts regarding the changed Indian psyche wrought by the West. Reflecting on the French Revolution, the efforts to abolish slavery and the upsurge of literary activity in Europe he wrote: “Western civilisation seemed to proclaim an inclusiveness for all humanity irrespective of race and colour. We were spell bound by Europe. We contrasted the generosity of that civilisation with the narrow mindedness of our own and applauded the West.” He goes on to say, however, that the scales had fallen from the nation’s eyes. The supposedly Western ideal had failed Indians. European education and adoption of its values hadn’t helped them to achieve equality with the white race.

Thus, the movement came full circle. Rabindranath had not been part of it from its inception. Yet, if one were to look for and identify a single persona in whom the entire Bengal Renaissance may be said to be epitomised, it would, without doubt, be the persona of Rabindranath Tagore.

Poet, playwright, novelist, painter, composer, educationist, nationalist and internationalist, Rabindranath was not only a myriad minded genius but a Renaissance Man in the truest sense of the word. In fact, the dawn or awakening of Rabindranath’s creative inspiration is synonymous with the awakening of a whole nation.

The cultural identity of India and the place in it of religion, caste, class and gender which much of Rabindranath’s prose and poetry explores, continue to retain their relevance even today, a hundred years later, in a post-colonial time frame. His novels offer masterly insights and analyses of the complexities of Indian life with its teeming contradictions; its rootedness in tradition as well its ability to assimilate and accommodate change.

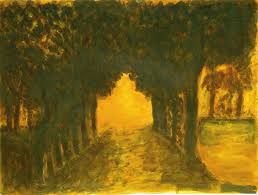

Rabindranath, however, is best known as a poet. His poetry, drawn from ancient cultural memory as well as the immediate present, is in a class of its own. For there is a third dimension to it. He not only wrote of what he saw and remembered but what he saw only in his mind — a world that lay a vast space away from reality. ” There are two kinds of reality in the world,” Rabindranath said[2] of his paintings. “One of them is true; the other truer.” He could have said this of his poetry too. The real and surreal quality of his images in the vast span of his poems and lyrics; their indefinable nuances and evocative power are comparable to the works of the great Impressionists.

Interestingly, Rabindranath arrived at the canvas through his poetry. The calligraphic erasures and corrections with which he embellished many of his poems became sketches of a special kind. “I try to make my corrections dance,” he said[3] once, “connect them in a rhythmic relationship and transform accumulation into adornment.”

Later, in the last thirteen years of his life he threw himself into frenzied bouts of painting leaving behind more than two thousand and five hundred art works. Strange, haunting faces with eyes that look deep into one’s soul; surreal landscapes the like of which were never seen this side of the horizon; trees and flowers painted in violent colours that erupt from the artist’s palette in volcanic bursts — his paintings, as an artist once said, reflect “emotions recollected more in turmoil than in tranquillity.”

Yet, though famed the world over for his poetry and painting, it is as a music maker that Rabindranath has stayed entrenched in the hearts of his own people. His songs, loved and sung by generations of Bengalis, range in theme from celebrations of nature and yearning for freedom to love of God and Man. They convey the poet’s profound philosophy of life, his deep faith in humanity and his sensitive exploration of the Universe, often touching on the quest of the unattainable. Rabindranath once said that, though he could not predict how future generations would receive the rest of his work, he was confident that his songs would live. The increasing popularity of Rabindra Sangeet, both in India and abroad, bears ample testimony to the fact that his prophecy was based on a certainty born out of self-knowledge. Vast and varied though his genius was — music was its mainspring. He wrote of his songs: “I feel as if music wells up from within some unconscious depth of my mind; that is why it has a certain completeness.”

[1] The Disease and its Cure, 190

[2] Quoted from Tagore’s Galpa Salpa (Conversations) by Soumendranath Bandopadhyay in Expressionism and Rabindranath

[3] Quoted in An Artist in Life by Niharranjan Ray

Aruna Chakravarti has been the principal of a prestigious women’s college of Delhi University for ten years. She is also a well-known academic, creative writer and translator with fourteen published books on record. Her novels Jorasanko, Daughters of Jorasanko, The Inheritors, Suralakshmi Villa have sold widely and received rave reviews. The Mendicant Prince and her short story collection, Through a Looking Glass, are her most recent books. She has also received awards such as the Vaitalik Award, Sahitya Akademi Award and Sarat Puraskar for her translations.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International