Book Review by Ajanta Paul

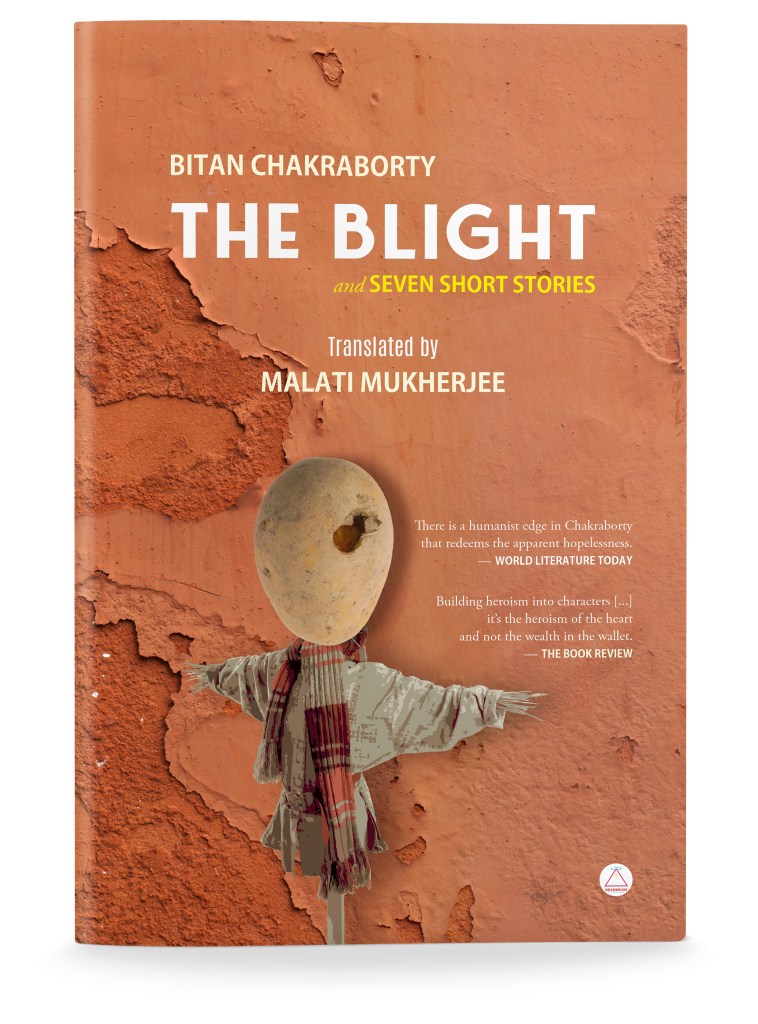

Title: The Blight and Seven Short Stories

Author: Bitan Chakraborty

Translator: Malati Mukherjee

Publisher: Shambhabi Imprint

Bitan Chakraborty’s The Blight and Seven Short Stories, translated by Malati Mukherjee from Bengali, heralds the arrival of a major talent in the sphere of short fiction, characterised as it is by an evolved narrative technique that raises the art of storytelling to a new pitch of intensity and subtlety.

The image of blight in the first and titular story is a metaphor that pervades the entire collection. Blight, as one knows, is an agricultural phenomenon, a term for a type of disease that affects crops and ruins harvests. In Bitan Chakraborty’s superb collection of stories, it symbolises the rot that has set in everywhere, the moral corruption that is eating away at the innards of society.

Characters such as Asesh, Neeladri, Karmakar and others are shown to have no conscience or scruples. They have little faith in the system and, therefore, have taken the law into their own hands, forging unholy alliances, negotiating shortcuts and demonstrating scant respect for traditional decencies. They are men in a hurry, eager to get rich quickly. Part of the local land-grabbing mafia and real estate “syndicate”, they are members of what Partha Chatterjee has described in his writings as a “political society.”

An evocative use of symbol and irony imparts a rhetorical depth to the conflicts enumerated. In the titular story, ‘The Blight’, for instance, the all-devouring, predatory and carnivorous instincts of Asesh are set against his father Moni’s ethics of integrity. Moni’s investigative methods intensify in the course of the story as he compulsively enquires about the prices of potato and potato products in a bid to assess the extent of Asesh’s deceitful dealings, his acts eventually spiralling into the surreal tableau at the end when father and son are locked in a physical struggle. Asesh’s relishing of his mutton just prior to this incident is an analogical and allegorical master stroke pointing to his material gluttony, insatiable appetite and ruthless self-gratification.

In the story. ‘The Site’, Neeladri, the son and Nalinaksh, the father are counterparts of Asesh and Moni, undergoing the same conflicts and revealing similar differences of opinion and values. Nalinaksh, however, is not untainted like Moni, neither is he impervious to the good life. It’s just that he cannot brook the scale of corruption indulged in by Neeladri. Is his end foreshadowed and pre-planned as seems to be suggested by the funeral card dropped surreptitiously in Hari’s bag?

In the short story ‘Reflection’, Ahan the Bengali protagonist, who is a vocal protester against habitual acts of indiscipline and injustice on trains, unwittingly indulges in the same, displaying disproportionate anger at an errant co-passenger for a minor infringement. The figure he is confronted by at the end of the story points to the ambiguity of his very being. Is this figure a self-reflection, an alter ego, or a doppelganger?

In ‘A Day’s Work’ and ‘The Mask’, it is Mahadeb, the debt-ridden and exploited daily wager, and Puntu, the suburban mask-seller who are manipulated by Karmakar, the jeweller-turned-moneylender and Shubho, the stage manager turned middleman respectively. In the latter story, the mask becomes a potent symbol of disguise used by perpetrators to conceal their wrongdoings. Shubho hides his questionable dealings in props as a theatre manager even as Neel conceals his affair with his office secretary.

In the story ‘Landmark’, Tapan goes to Delhi for work and decides to visit his friend Jashar in Ghaziabad. He sets out on the journey but fails to reach his destination because the landmark known to him has disappeared. His aborted journey becomes a symbol of the frustrated quest of modern man who fails to progress despite registering movement. One is reminded of the hapless souls trapped in the different circles of hell in Dante’s Inferno, even as shades of Joyce’s Dubliners are evident in the circling of Lenehan within the city of Dublin in the short story ‘Two Gallants’.

The landmark in question, namely two adjacent butcher’s shops at the mouth of a lane, had fallen prey to fundamentalist ire over the meat-eating habits of certain communities. The story has not so much a climax as an anticlimax in the revelation of the convenience store owner who enlightened Tapan about the fate of the owners of all such establishments in the area — they had been chopped into mincemeat and fed to unsuspecting patty consumers. This is gallows humour of the most effective kind and is directed at Tapan whose mouth is filled with the particular savoury at that moment.

In ‘Spectacles’, Siddharth has been wearing the wrong pair of spectacles and consequently not seeing things clearly. The trope of a skewed perspective is evident in his youthful misjudgment of Sameerda to have been a man of ideals. In ‘The Site’, Nalinaksh cannot understand what the beggar down below on the street is telling him so urgently just moments before his fall from the balcony and subsequent death, symbolizing a lack of communication.

Historically, ‘blight’ was a sociological term applied to urban decay in the first half of the twentieth century. Usually associated with overcrowded, dilapidated and ill-maintained areas affecting built structures and civic spaces, the term has this palpable air of dereliction which, translates into a pall of moral disrepair that dooms the situations in the mentioned stories with an inevitability, reinforcing the significance of the title in its varied connotations.

In an epical sense, the conflict in the stories is between the forces of good and evil. It is also between social classes, and Moni comes across as the tired torchbearer of a jaded idealism whose dedication to his cause is regarded by some as whimsicality, so ingrained and ubiquitous is the sense of blight. The moral protesters in Moni, Nalinaksh, Ahan, Subal and others, for all their integrity, are shown to be largely ineffectual in their opposition to venality. Nevertheless, they are entirely credible within the ambit of their operations.

Immoral and illegal activities, found in almost every story in the collection, yield a cumulative effect in the final story, ‘Land’, where an entire village, having fallen prey to unscrupulous land appropriation, lies desolate and ghostly. The poignant reality of dispossession is brought home most vividly in the isolation of the young bride-turned-widow, Manasa, who, by the end of the story, spends her days gazing at her husband’s burial site from her window.

Real estate is not only a veritable canker but almost a narrative device in its variations and applications in this clairvoyant cluster of stories. It is one’s native soil and eventual resting place (‘Land’); dream or fantasy (Mukto’s in ‘The Blight’); make-believe space of the theatre in ‘The Mask’ and the rough and tumble of property dealings in ‘The Site’, ‘Spectacles’ and of course, the titular story.

The modernistic slant of the collection is expressed with objectivity without authorial interventions and, consequently, the lack of any judgemental attitude. Yet, Chakraborty successfully suggests there is no law and order, justice or tolerance in contemporary society, only a wide chasm between the haves and the have-nots which is aggravated with every passing day as he repeatedly portrays ordinary people as having no rights, voice or means to fight the corrupt.

He does this with postmodern techniques of flux, erasure and revision. Nothing is permanent, and the provisional truth of the moment is glimpsed through opposites, overlaps, continuities and breaks. A case in point would be the friction between different kinds of betrayal as in ‘Spectacles’ — Sameer-da’s wife had discovered an indifferent and unhelpful side to Siddharth’s nature even as the latter believed Sameer-da to have been what he was actually not.

In ‘The Blight’, the space between the contesting narratives of deliverance and deviance, the first pertaining to Monì and the second to Asesh holds the developing interest of the story within its escalating spiral. Between realism and surrealism, in the same story lies the flitting apprehension of the truth of Asesh’s character as he tears into the flesh of an animal while enjoying his Sunday lunch of mutton and rice.

The meanings of Chakraborty’s stories cohere in the consequences of both commission and omission. In ‘Land’, for instance, momentous developments such as the death of Subal are scarcely mentioned, modernistically enacting the crisis through structure and style. The piece seems to be caught in a curious aesthetic apathy in which gaps and ellipses in the mode of narration express the emptiness at the heart of Manasa’s life and those of others like her.

The translation helps through the fluid grace with which it transliterates, transcribes and transcreates the stories from one language to another, all the while trying to retain the nuances of the root culture. This same culture is sought to be portrayed through two languages with very different socio-cultural associations, the first being the original Bengali in which it was composed and the second a colonial legacy notably indigenised. Malati Mukherjee has a keen ear for voice, accent and dialect, which aids her in effecting an authentic idiomatic equivalence, at once elucidating and engaging.

Two passages stand out for the haunting beauty of their description. One is the spectacular reference to the world’s oceans and forests contained in the aquarium and the balcony garden in ‘The Blight’, and the other is the luminous lambency of the moon in ‘Land’ as it broods over the melancholy landscape. Bitan Chakraborty’s stories in this collection are rare blooms depicting a moral topography in torpor where character, setting and style intersect to create points of extraordinary insight.

Dr Ajanta Paul is a poet, short story writer and literary critic. She is currently the Principal at Women’s Christian College, Kolkata. Her publications include a book of poetic plays — The Journey Eternal; a collection of short stories — The Elixir Maker and Other Stories; a book of literary criticism — American Poetry: Colonial to Contemporary; three books of poems — From the Singing Bowl of the Soul: Fifty Poems, Beached Driftwood and Earth Elegies.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International