By K.N. Ganguly

I live in a small flat in London. I teach in a school here, the students of which are mostly of Asiatic and Caribbean origin. Every morning I leave my flat after breakfast, which I make myself. I dine out and return to my flat around ten every night. I have very few friends but I know quite a few Indians who come to London regularly on business or on holiday.

It was a Sunday morning. I was still lolling in bed, soaking in a mixture of laziness and fresh air, when my telephone rang.

I picked up the receiver sleepily and said, “Hello?”

“Monty, this is Jhun Jhun,” came the reply. “I want to meet you just now.”

I became alert at once. “Jhun Jhun, what is it about?”

“It’s something serious, really serious. I am in deep trouble. I’ll tell you everything when I meet you.”

“Come along, then,” I said. “I’ll be waiting for you.” Jhun Jhun’s real name was Rajesh Jhunjhunwala. He was a diamond merchant. We knew each other from our school days, and we were good friends. He made it a point to look me up when he came to London. Occasionally, we spent weekends together on the seafront. Jhun Jhun owned a small bungalow outside London.

I had just got dressed when a cab stopped outside my flat. Jhun Jhun paid the cabbie, then hurried in, but paused a moment outside the door. As soon as he entered the flat, he locked the door, then peered through the roadside window. His podgy face certainly looked disturbed. I made him sit on a sofa. Then I gave him a cup of tea and asked him to tell me his story.

“Well, it’s a long story. As you know, I’m in the diamond business. It’s a small firm really, and I thought I could do better if I tied up with some other diamond merchants. So, about six months ago, I posted a notice on my website seeking business contacts with other diamond firms. There was hardly any response, but that was only to be expected. The diamond trade is controlled by cartels which fiercely guard themselves against poaching by outsiders. And then, I got a pleasant surprise. Someone who introduced himself as Nobles contacted me. He promised to give me tips about family jewelry held as heirlooms by old and noble families, now impoverished and eager to dispose them off secretly. He also expected similar gestures from me, which I promised to do.

“I didn’t hear from Nobles again till last week. He said he would send me a diamond for valuation. But there was no real hurry. I could keep the diamond with me, a la ‘The Purloined Letter’ by Edgar Allan Poe. He would collect it from me, and of course, there would be a consideration for my services. I had read the story of ‘The Purloined Letter’ in school. I understood that Nobles wanted me to keep the diamond in an easily accessible place rather than in a safe, so as to hoodwink criminals if they got wind of it.

“That very night around 3 a.m., my doorbell rang. As I opened the door — you know, I stay alone in my house — I saw a man with a moustache wearing a hat and dark glasses. He drew out a small packet from the inside pocket of his coat, gave it to me and vanished. All this happened so fast that I hardly noticed the face of the man or his general appearance.

“Anyway, I locked the door and went to my bedroom. When I opened the packet, I was simply dazzled. I had never seen a diamond of this size. It sparkled from all angles. My immediate assessment of the value of the diamond was between one and one-and-a-half million pounds. However, I left the diamond in a tin box containing buttons, skeins of thread and needles. Surely no one would look for a priceless diamond in a tin box left on the dressing table. Every day I checked the tin box to assure myself that the diamond was still there. But last night, to my horror, I found the diamond missing.

“My first thought was to call the police, but I immediately checked myself. I didn’t know the antecedents of Nobles. Besides, how could I be sure that it was not a stolen diamond? On the other hand, Nobles was bound to hold me responsible for the loss of the diamond. He might even suspect that I had caused the loss intentionally with the help of my associates.

“So here I am, Monty. I am not even able to think anymore. I have many acquaintances in London, some in high places. But you are the only one to whom I could confide a matter like this.”

I understood the seriousness of the problem but managed to stay calm. Suddenly I remembered my schooldays’ hero. “Eureka!” I shouted. “Come on, let’s go to Sherlock Holmes!”

“Sherlock Holmes? Are you mad, Monty? Holmes will have been dead many years now!”

“How do you know? Vitamins and medicines can rejuvenate and prolong life. Well, he may not be active now, but it is the mind that matters. Let’s find out from the telephone directory.”

I looked up the Telephone Directory and was happy to find in it, Holmes, Sherlock, 21B Baker Street.

“Come, we’ll catch him now”, I said and simply dragged my friend out of the house.

When we arrived at Holmes’ address, we found it was a very old, rather shabby building. We pressed the bell at the entrance door and within a few minutes, the door was opened by an old and wizened woman wearing an apron and a very pleasant smile. “Good morning, gentlemen. Do you want to see Mr. Holmes on some very urgent business? Well, please come in.”

We were ushered into a large sitting room. The floor was covered with an old, worn-out carpet. There were a couple of sofas, several easy chairs and a rocking chair. At one side of the room, there was a marble-topped table with a pipe, an umbrella and a violin on it. There was a grand piano at one end of the room and photographs of Sherlock Holmes covered practically all the walls. I was taken aback. Was it a Sherlock Holmes Memorial and was the old woman merely trying to tease us? Just then, two middle-aged gentlemen entered the room—one, tall and gaunt with clean features, the other a bit swarthy and portly. The tall gentleman said, “I am Sherlock Holmes, and this is Dr. Watson. Those are my grandfather’s memorabilia that you were looking at. Dr. Watson is also the grandson of my grandfather’s friend.” At this stage, Dr. Watson came forward and shook my hand. “I am Anil Watson,”he said.

“Anil or O’niell?” I asked. “Anil is an Indian name.”

“Yes, I am part Indian,” he replied. “You see, my father, also a doctor, married a fellow-student who happened to be an Indian. My mother named me Anil.”

We introduced ourselves. “I am Montu Gangaur, Monty Gang for short. This is Rajesh Jhunjhunwala, better known as Jhun Jhun.”

“Fine. Well, gentlemen, I know you have come to see me on a specific problem of yours. We will get down to business shortly, but before that, I would like to indulge in a game, as was my grandfather’s practice. You may call it a guessing game, but it helps sharpening the intellect. Now, Watson, please take a quick look at Mr. Monty Gang’s face and tell me what impression you get.”

“Well, it’s a round face, evidently his eyes are weak, his thick glasses give that away. He is bald as a pumpkin, it’s likely that baldness runs in his family. Also, he frowns from time to time. That implies impatience. Besides, he likes to hear his own voice more than that of others’. Well, that’s about all. I hope you haven’t taken any offense, Mr. Gang?”

“Of course not,” I said.

“Excellent, Watson,” said Holmes. “That was a very good exposition. But didn’t you notice that the colour of the skin above his brow is slightly lighter than that of the rest of his face? Then, watch his eyes. Did you notice that when Mr. Gang was looking at the marble-topped table to his left, his head had turned completely to the left. Had his left eye been functioning, he wouldn’t have done that. But his left eye is not completely sightless. Watch him closely, Watson. Well, Mr. Gang, what did you think of my deductions?”

I was startled. “You were simply marvelous, Mr. Holmes. Yes, I was involved in an air-crash, which left burns on my scalp and my left eye is severely damaged but not sightless.”

Holmes now looked at Jhun Jhun, who was sitting quietly, puffing away at his cigar. “Now, Mr. Jhun Jhun, you’re a diamond merchant, aren’t you? And you have close connections with South Africa — Johannesburg, to be precise. Would I be correct in saying that the cigar you are smoking is a gift from your South African principals?”

Jhun Jhun was visibly surprised. “Well, Mr. Holmes, how did you know that I am a diamond merchant, or that this cigar was a gift to me from the diamond merchants of Johannesburg?”

“Quite elementary, Mr. Jhun Jhun. If you smell your cigar smoke, you will find there is a very slight rose scent in it. This unique variety of tobacco was produced by a Spanish planter in Cuba about two hundred years ago by crossbreeding tobacco and rose plants. His African slave killed him in a fit of temper, destroyed his plantation and ran away with a few specimens. Ultimately, he found shelter in Johannesburg and sold the secret plants to a diamond merchant. From then on, this variety of tobacco has been grown by that diamond family and used exclusively for business promotion.”

Jhun Jhun did not know what to say. His first reaction was that Holmes must have learnt of it from some of his friends. Then he realized that was absurd, as no friend of his, not even I, knew about the origin of that cigar. “Well, Mr. Holmes,” he mumbled, “you are a genius.” Holmes puffed his pipe and looked at Watson. Then he smiled and said, “Well, now let us get down to business.” Jhun Jhun repeated what he had said to me. Holmes asked him, “On which day did you get the diamond?”

“Wednesday night or Thursday morning, whatever you choose to say.”

“And it disappeared yesterday, that is on Saturday.” He closed his eyes and puffed away for some time, then dialed on his telephone.

“Inspector Wilson?” Holmes said. “This is Sherlock Holmes. I read in the papers about the theft of Baroness Rothschild’s Nefertiti diamond. I also know that the French diamond thief Charles Dupin came to London a few days ago. Have you thought about the obvious link between the two events?”

The reply from the other side was quite audible. Wilson was saying, “Look here, Holmes, it seems you are as pompous as your so-called famous grandfather. Do you think we are so dim-witted we wouldn’t turn the heat on Dupin? In fact, my men have been tailing him constantly since the disappearance of the Nefertiti diamond. Let me tell you, Holmes, Dupin seems to be a reformed man. He said he had come here as a tourist. We found he basked in the sun in Hyde Park, fed the pigeons at Marble Arch, even watched the Change of Guards at Buckingham Palace. He is a well-read man and can be quite witty. Despite all this, we made a thorough search of his hotel room and even brought him to the Yard for a further personal search. Well Holmes, there was nothing—absolutely nothing—incriminating on him.”

“Look, Wilson, I have no time to argue with you. Right now, I have enough evidence that proves his complicity. He must be on his way to France, but you may yet be able to catch him if you make an all-out effort straightaway. I would also suggest that when you get him, do not leave anything — pen, wrist-watch or cigarette lighter — out of a minute scrutiny. In particular, a cigarette lighter would provide ample scope for hiding a diamond in a special compartment. Well, I leave you to your job now. Don’t forget to inform me when you have retrieved the diamond.” All of us were watching Holmes, who quietly put down the receiver and said, “Gentlemen, we are all very hungry. Let us walk down the Strand and find a good restaurant.”

It was lunchtime. Most of the restaurants were crowded, but we found a quiet corner in a small place. Holmes asked Watson to place the order for all of us. I noticed he was somewhat edgy. And then his cellphone rang. “Holmes? This is Wilson. Thanks for the tip. We were able to catch Dupin just when he was about to leave the hotel. Well, your guess was right. The diamond was concealed in his cigarette lighter. You know, Holmes, he had cupped the lighter and was pretending to light a cigarette. Looked very natural. But I remembered your warning and grabbed the lighter. Indeed, there was a compartment at the lower end of the lighter and inside it lay the diamond.”

After lunch, we exchanged pleasantries and returned to our respective places. Next morning, we again went to meet Holmes to find out whether there was any suspicion on Jhun Jhun. Holmes was very pleasant. He asked us to join him at breakfast and then said that Jhun Jhun was absolutely in the clear, as there was no evidence against him, nor had Dupin mentioned his name. Just then, the doorbell rang, and the old maid went to answer it. She came back shortly, accompanied by a liveried chauffeur. “Baroness Rothschild’s compliments, Sir,” said the man and handed Holmes a small packet. Holmes unwrapped it slowly, and inside was a velvet case containing an exquisite diamond ring for all of us to see.

“Well, well! Wilson is not a bad fellow after all! He must have mentioned my name to the Baroness, instead of taking the credit himself.”

Holmes was standing with the gift. It was clearly time for us to leave. We stood up. “Mr. Holmes, we are grateful to you for all the help and courtesies extended to us. Jhun Jhun is now a relieved man, and as his friend, I also share his relief. I have read so much about the exploits of your legendary grandfather, but I think the grandson’s brilliance is not a bit less.”

Holmes looked a bit embarrassed. “Your compliments flatter me, Mr. Gang. I see you are ready to leave now, but I have a feeling you would like to hear the whole story, as the snatches you have heard so far leave many gaps.” Holmes then led us to the sitting room. “Please sit down, gentlemen”, he said, and then sat down on the rocking chair. He took some time to take out his pipe, fill it carefully with tobacco and light it. “Well, gentlemen, here is the full story. But let me caution you beforehand. In the absence of hard facts, I had to depend equally on conjecture and logic. The whole truth will no doubt come out after the police have finally interrogated Charles Dupin, but I am sure it will not substantially alter my story. Here it is then.”

“As I told you before, the Rothschild clan is spread over several continents and countries. They started about two hundred years ago as bankers but over the last century, they moved into shipping, industry, mining, real estate, etc. and acquired immense wealth. It is said that the Nefertiti diamond also came into the family a little over a hundred years ago. The clan members — at least the majority of them — believe they owe their sharp rise to prosperity to this diamond and therefore look upon it with reverence. Traditionally, Baron Rothschild is regarded as the head of the clan, and therefore is the custodian of the diamond, which is kept in a special vault in Lloyd’s Bank. However, the clan holds an annual banquet in Baron Rothschild’s mansion, which is attended by representatives of all its branches. Evidently, a banquet was held last Saturday. It is customary for the Nefertiti Diamond to be kept in the Rothschild mansion hall for two days, prior to the banquet for viewing by the clan members. The diamond should therefore have been on view from Thursday last week and brought to the mansion from the bank on the previous day, that is, Wednesday. As per Mr. Jhun Jhun’s statement, it was handed to him at around 3 a.m. on Thursday morning. Assuming the diamond was taken out of the bank at about 4 p.m. on Wednesday, the theft should have occurred within the next ten hours or so. But who could have stolen it? Obviously, Dupin could not have had access to the mansion, or known precisely where it was kept. There would also be family members and domestic staff all over the place and a stranger would be easily spotted. No, I don’t think it was Dupin, it must have been an inside job. But the person was Dupin’s accomplice, for he took the diamond to Jhun Jhun’s place as per Dupin’s plan. The insider could be a family member or a domestic help.

“Baron Rothschild’s second son is known to have a dubious reputation. He seems always to be involved in one scandal or the other and his name appears on the gossip columns of the newspapers more than once a month. However, I can’t imagine him as an accomplice of Dupin, because the risk would be too high for him, and also, one or two credit him with some loyalty to the family.

“Then come the domestic staff. Since the diamond would be removed to the hall the next morning, I would presume the Baron would keep it in his personal suite on Wednesday. Normally, only senior staff members like the valet or the senior maid would have access to the Baron’s suite, and I wouldn’t expect any of them to be foolish enough to indulge in such a job and risk their careers and reputation. It is more likely that Dupin’s accomplice joined the staff as a junior member — there would always be a need for an extra man or a substitute, for instance, when the valet wants a day off for temporary relief or they need a replacement. I’m sure Dupin would have found a man, pleasant-looking and well-behaved, with a few forged references. A place in the mansion would not be difficult to find.” Sherlock Holmes stopped for a while to re-light his pipe. I wanted to know a little more about the diamond ritual. “Did you ever attend any of these banquets, Mr. Holmes?” I asked him.

“I’m afraid not, but my grandfather did. And there’s a lovely bit recorded by him about this ritual. Wait, I’ll read it out to you,” Holmes said, and went to one of the bookshelves lining the wall. He pulled out a leather-bound volume and thumbed through the leaves. Then he found the right page and returned to us with the book in his hand. “Now, listen to this –

‘Sherlock was sitting quietly in his rocking chair smoking his pipe, seemingly lost in thought when Watson walked in. “Good morning, Holmes,” he said. “You seem to be in a pensive frame of mind. Did anything go wrong at yesterday’s banquet? Or perhaps the food didn’t agree with you!”

‘“Oh, no, no! The arrangements were excellent, the party was exhilarating, and the food was indeed very good. It was really the spectacle of the Nefertiti diamond ritual that moved me. As you know, the annual banquet at the Rothschild mansion is meant for the members of the Rothschild clan. But many distinguished people like writers and artists, eminent in their own field, are invited. I had the good fortune to attend the banquet a few years ago. Before the start of the banquet, the guests were taken to a large hall, at one end of which there was a glass case on a heavy rosewood table fixed to the floor. The glass case had a wooden frame which was screwed to the table. Inside the case lay the famous Nefertiti diamond on a velvet cushion.

‘“When I looked at the diamond, my whole being was filled with awe. It was a brilliant diamond sparkling from all angles. It was something like a brilliant star. Well, the sun is also a star, but when you look at the sun, it not only dazzles you, but also burns your eyes, so to say. But imagine a star shining with as much luster as the sun, but its sparkling rays as soothing as the spouting waters of a fountain. Then, I watched a strange spectacle: a row of clan members passing by the glass case mutely and reverently as if it were some holy object. I don’t know Watson, whether you will believe it. Suddenly it seemed to me that I was standing in front of the glass coffin of the magnificent Queen Nefertiti in ancient Egypt and rows of noblemen were passing by it in deep veneration. You know, Watson, it left in me a feeling of awe. Somehow, I’ve not been able to overcome it. You might say, I’m still in a trance,” he laughed.’

“I hope you will now be able to understand the value of this diamond to the Rothschilds, and the deep shock they must have gone through after its disappearance.”

I said, “Mr. Holmes, I have a complete set of Sherlock Holmes stories which I read and re-read in my childhood and also when I grew up. Strangely, I don’t recall having come across the passage you read out to us just now. I always thought the original Sherlock Holmes was a pragmatist, and that his driving force was logic and reason. But now I know there was also a romantic trait in him. But now, let’s go back to the rest of the diamond case. One thing that intrigues me is how you guessed that Dupin would have kept the diamond concealed in his cigarette lighter.’

“Oh, that’s quite a simple guess, isn’t it! You see, practically everybody carries a pen and a watch. A smoker also carries a cigarette case and a lighter. Normally these are used openly, and one wouldn’t suspect them to be hiding places. A cigarette case is in any case quite inappropriate, because it doesn’t have any place to hide anything. A watch or a pen would be quite inconvenient for hiding a diamond. So, I thought the lighter would be the most likely object. It was only an inference after all, but it clicked. Any more questions, gentlemen?”

I looked at Jhun Jhun. He nodded his head as if to signify he had none. I said to Holmes, “I think our curiosity has been satisfied. No, we have nothing further to ask you. You have given us a lot of your time and your patience is limitless.”

Holmes stood up. “It has been my pleasure,” he said and shook our hands warmly.

When we came out of the house, Jhun Jhun said, “The old man Sherlock Holmes was an amazing man, wasn’t he? I wish we had someone like him in our diamond business. There is such a lot of cheating and forgery in the business and there is none to protect an honest man!”

.

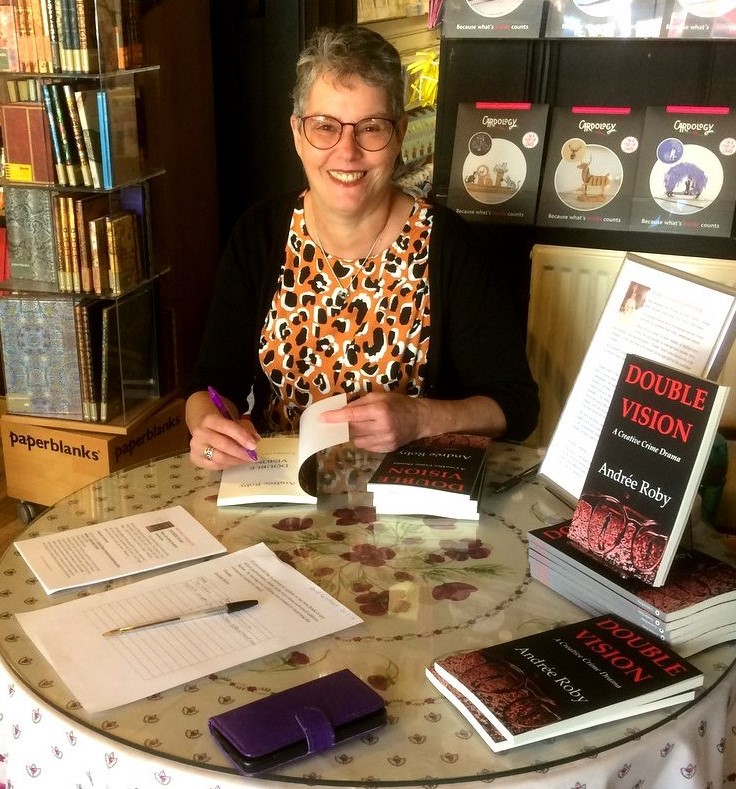

Mr. K.N. Ganguly was born in 1924, did his schooling in many of the smaller towns of undivided Bengal, and then Calcutta. He graduated with Honours in History, from Presidency College. He then joined Law college but did not attain the degree as he joined the Calcutta Port Commissioners (today’s Kolkata Port Trust) in 1945. He retired from the Port in 1982, after a long career which witnessed many changes in his city and country. An avid reader, his interests covered many genres, ranging from fiction and crime fiction to biographies, travelogues and political essays. He is not a published writer but has always been fond of writing.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.